Allegations regarding “Butch” Merritt, Watergate, Intelligence Agencies and “Crimson Rose,” Vol. II

Agnostics for Nixon, Part One

Written (and first posted) by Kris Millegan, March 16, 2011

I am being the devil’s advocate … President Nixon, White House Tapes, March 13, 1973

Richard Milhous Nixon tried to be his own man, yes, sometimes he was the creature of others, but at the end of the day, he attempted to run his own show … and lost. You see, Tricky Dicky was a blackmailer.

Nixon’s political career began when he was elected to the 80th Congress in 1947 along with 107 other freshmen representatives, including future rival John F. Kennedy, future speaker Carl Albert and future senators Jacob Javitts and George Smathers. There they joined future president Lyndon Johnson, who had been in the House since 1939. In 1949 LBJ moved on to the Senate, just when another future president Gerald Ford showed up to serve in the House of Representatives.

Just as Richard Nixon tells several different stories about where he was when President Kennedy was assassinated, there are several different tales about how Nixon became involved in politics.

In the 1979 Memoirs of Richard Nixon, he writes about receiving a letter from the manager of the Whittier branch of the Bank of America, Herman Perry:

“Dear Dick, Do you want to run for the Republican ticket? Airmail me your reply. HL Perry”

And at the Nixon Library website they glorify the anniversary date of the famous letter as September 29, 1945 and Nixon’s reply of October 6, 1945, where he writes, “I feel very strongly that Jerry Voorhis can be beaten and I’d welcome the opportunity to take a crack at him.” The website states “Nixon was a young up-and-coming attorney, a graduate of Duke University Law School, and a naval officer during World War II who had returned to his hometown of Whittier to work at an established law firm”

Conrad Black writes in 2008 in Richard M. Nixon: A Life in Full, that Nixon telephone Perry on October 1st and then wrote his letter on October 2.

In Nixon by Nixon admirer Ralph De Toledano written in 1956, we learn about an ad placed in 26 newspapers by a Committee of One Hundred Men:

“WANTED — Congressman candidate with no previous political experience to defeat a man who has represented the district in the House for ten years. Any young man, resident of district, preferably a veteran, fair education, no political strings or obligations and possessor of a few ideas for betterment of country at large may apply for the job. Applicants will be reviewed by 100 interested citizens who will guarantee support but will not obligate the candidate in any way.”

De Toledano’s Nixon says the first contact was by phone, that Nixon received a telephone call from Perry, who asked “Are you a Republican and are you available?”, while Nixon was still living in Maryland and in the Navy.

What did Nixon do in the Navy? Again there are many different versions.

Here is wikipedia’s blurb:

“Nixon was eligible for an exemption from military service, both as a Quaker and through his job working for the OPA, but he did not seek one and was commissioned into the United States Navy in August 1942. He was trained at Naval Air Station Quonset Point, Rhode Island and was assigned to Ottumwa Naval Air Station, Iowa, for seven months. He was subsequently reassigned as the naval passenger control officer for the South Pacific Combat Air Transport Command, supporting the logistics of operations in the South West Pacific theater. After requesting more challenging duties, he was given command of cargo handling units. Nixon returned to the United States with two service stars (although he saw no actual combat) and a citation of commendation, and became the administrative officer of the Alameda Naval Air Station. In January 1945, he was transferred to Philadelphia’s Bureau of Aeronautics office to help negotiate the termination of war contracts. There he received another letter of commendation, this time from Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal. In October 1945, he was promoted to lieutenant commander. He resigned his commission on New Year’s Day 1946.”

According to Mae Brussell, in “How Nixon Actually Got Into Power” from The Realist, Aug 1972, Nixon was working under “special orders”:

“Nixon’s 15 months in the South Pacific ended when he was transferred to Fleet Air Wing 8 at Alameda, California, and from there he was assigned on special orders to the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics. The Navy assigned him to “winding up” active contracts with such aircraft firms as Bell and Glenn Martin.(19)”

“As a Lieutenant Commander in the Navy, Richard Nixon’s next task was that of “negotiating settlements” of terminated war contracts in the Bureau of Aeronautics Office at 50 Church Street, New York City.(20)”

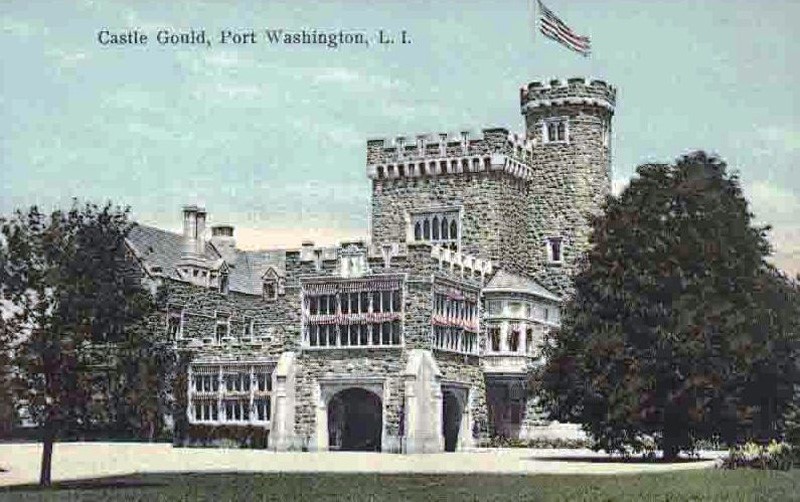

“That year was 1945, when importation proceedings began for the 642 Nazi rocket and aerospace experts and scientists from Germany to the U.S. Through the “generosity of the Guggenheim Foundation they obtained a suitable site — a huge medieval castle, built by financier Jay Gould on a 160-acre estate at Sands Point, Long Island. Here the Germans began work on a secret project for the Navy’s Office of Research and Inventions.(21)”

“19. Alameda, air contracts – Nixon, RaIph De Toledano, Duell, Sloan, Pearce, Page 37

20. New York, Contracts– My Six Crises, Richard Nixon, Pyramid Books, 1962, Page 81

21. Importation of Germans – Project Paperclip: German Scientists and the Cold War, Clarence Lasby, Atheneum Press, 1971, Pages 4-5″

Here is Russ Bakers take on Nixon’s rise, from Family of Secrets, 2009:

“Nixon’s Big Break“

“In Nixon’s carefully crafted creation story, his 1945 decision to enter politics was triggered when the young Navy veteran, working on the East Coast, received a request from an old family friend, a hometown banker named Herman Perry. Would he fly back to Los Angeles and speak with a group of local businessmen looking for a candidate to oppose Democratic congressman Jerry Voorhis?? They felt he was too liberal, and too close to labor unions.

“The businessmen who summoned Nixon are usually characterized as Rotary Club types-a furniture dealer, a bank manager, an auto dealer, a printing salesman. In reality, these men were essentially fronts for far more powerful interests. Principal among Nixon’s bigger backers was the archconservative Chandler family, owners of the Los Angeles Times. Nixon himself acknowledged his debt to the Chandlers in correspondence. “I often said to friends that I would never have gone to Washington in the first place had it not been for the Times,” he wrote. Though best known as publishers, the Chandlers had built their fortune on railroads, still the preferred vehicle for shipping oil, and held wide and diverse interests. Yet Voorhis appears to have recognized that forces even more powerful than the Chandler clan were opposing him. As he wrote in an unpublished manuscript, “The Nixon campaign was a creature of big Eastern financial interests … the Bank of America, the big private utilities, the major oil companies.” He was hardly a dispassionate observer, but on this point the record bears him out. Nixon partisans would claim that “not a penny” of oil money found its way into his campaign. Perhaps. But a representative of Standard Oil, Willard Larson, was present at that Los Angeles meeting in which Nixon was selected as the favored candidate to run against Voorhis.

“Representative Voorhis had caused a stir at the outset of World War II when he exposed a secret government contract that allowed Standard Oil to drill for free on public lands in Central California’s Elk Hills. But the establishment’s quarrel with Voorhis was about more than oil. While no anticapitalist radical, Voorhis had a deep antipathy for corporate excesses and malfeasance. And he was not afraid of the big guys. He investigated one industry after another – insurance, real estate, investment banking. He fought for antitrust regulation of the insurance industry, and he warned against the “cancerous superstructure of monopolies and cartels.” He also was an articulate voice calling for fundamental reforms in banking. He knew Wall Street was gunning for him. In his memoir, Confessions of a Congressman, Voorhis recalled:

“The 12th District campaign of 1946 got started along in the fall of 1945, more than a year before the election. There was, of course, opposition to me in the district. There always had been. Nor was there any valid reason for me to think I lived a charmed political life. But there were special factors in the campaign of 1946, factors bigger and more powerful than either my opponent or myself, And they were on his side.”

“In October 1945, the representative of a large New York financial house [emphasis Baker’s] made a trip to California. All the reasons for his trip I, of course, do not know. But I do know that he called on a number of influential people in Southern California. And I know he “bawled them out.” For what? For permitting Jerry Voorhis, whom he described as “one of the most dangerous men in Washington,” to continue to represent a part of the state of California in the House of Representatives. This gentleman’s reasons for thinking me so “dangerous” obviously had to do with my views and work against monopoly and for changes in the monetary system.” [End Voorhis.]

“It is not clear whether Voorhis knew the exact identity of the man. Nor is it clear whether Voorhis knew that his nemesis, the Chandler family, had for several years been in business with Dresser Industries. The latter had begun moving into Southern California during the war, snapping up local companies both to secure immediate defense contracts and in anticipation of lucrative postwar opportunities. One of these companies, Pacific Pump Works, which manufactured water pumps, later produced components for the atomic bomb. The Chandlers were majority shareholders in Pacific Pump when Dresser acquired the company, and so gained a seat on the Dresser board, along with such Dresser stalwarts as Prescott Bush. But there was even more of a Bush connection to the movers and shakers behind Nixon’s entry into politics.

“In October 1945, the same month in which that “representative of a large New York financial house” was in town searching for a candidate to oppose Voorhis, Dresser Industries was launching a particularly relevant California project. The company was just completing its purchase of yet another local company, the drill bit manufacturer Security Engineering, which was located in Whittier, Nixon’s hometown. The combined evidence, both from that period and from the subsequent relationships, suggests that Voorhis’s Eastern banking representative may have been none other than Prescott Bush himself. If so, that would explain Nixon’s sense of indebtedness to the Bush family, something he never acknowledged in so many words but clearly demonstrated in so many actions during his career.” [End of Russ Baker.]

And then there is the tale former Justice Department investigator and author John Loftus tells in America’s Nazi Secrets, 2010:

“When Richard Nixon was a naval officer, he was assigned to the Brooklyn Navy Yard to review captured German financial documents, some of which, according to legend, involved the Dulles brothers and their clients. The Dulles brothers promptly financed Nixon’s first run for Congress and then prevailed upon Eisenhower to take him on as Vice President. Australian intelligence records confirmed that President Nixon used the eastern European Nazi vote as his ethnic counterweight to the Jewish vote for the Democrats in five key states.”

Hmm, if Nixon is blackmailing the Dulles brothers, that could explain a few things.

Such as this from Howard Blum’s Wanted! Search for Nazis in America, where we again run into Mr. Herman Perry of Whittier, California:

“The gray farmhouse was surrounded by shouting men. A rock crashed through a window. Other stones slammed against the front door and roof. Stefan Feraru tried to call for help, but it was useless: The telephone lines had been cut. At least a hundred men crowded the finely shaven green lawns stretching from the road to the main house. Most were just observers, up from Detroit for a fine summer’s day in the country. The crowd, though, had been drinking and the alcohol and sun mixed to make them restless and aggressive. Many, waving their bottles in the air, started chanting in a tough, loud cadence: “Com-mun-ists … Com-mun-ists … ” At the head of the lawn, directly in front of the farmhouse, was a more menacing group of approximately thirty men. They were neither drunk nor merely restless. They had planned the assault on the Rumanian Orthodox Episcopate in Grass Lakes, Michigan, as if it were a military operation: first the phone lines would be cut, a barrage of rocks, and then the final push – the seizure of the Vatra. In fact, many of these men were trained soldiers. They had been trained twenty years ago in Rumania when they fought with the Iron Guard.

“These men, some brandishing broom handles, advanced toward the house. A priest’s new Buick directly in their path became an easy target: Windows were smashed and tires slashed. Another volley of rocks was thrown as they moved closer. Inside the farmhouse, Bishop Moldovan and his priests began to panic. “We were scared,” Stefan Feraru remembered. “We had come to the Vatra a few days early to prepare for the annual church congress. We knew there would be some discussion, some debate, but we never expected an attack. These men were wild.”

“Father Oprean, a short priest with a long, gray beard, decided he could stop the assault; he believed no one would attack a priest dressed in his black cassock, a cross hanging from his neck. He walked out to the front porch and raised his arms, appealing for quiet. “Fellow Christians,” he began. But before he could continue, he was dragged from the porch. Clutching the priest’s beard, the attacker spun the priest as if he were a child’s top into the crowd. Men surrounded the priest, pushing, punching, and kicking until Father Oprean fell to the ground. He lay dazed, a small, old man, his black cassock spread about the green grass like a discarded rag.

“Bishop Moldovan had no choice but surrender. If a battle were to be fought, he would have to wage it in an American court. On Independence Day – July 4 –1952, he surrendered the two hundred-acre-farm in northern Michigan to the priests and supporters of the newly chosen dissident bishop – Valerian Trifa.

“The Reverend Vasile Pascau, Bishop Moldovan’s secretary, had been inside the farmhouse during the assault and later wrote: “… a group of Iron Guardist hoodlums … invaded our property … beating an old priest … creating terror among our women, children, and old people, exactly as Hitler did once in Germany against the Jews. After this kind of ordeal, they took over our property by force, chasing us out.”

“On Wednesday, May 11, 1955, Bishop Trifa had the honor of offering the opening prayer before the U.S. Senate … Trifa’s presence had been requested by Vice President Richard M. Nixon.

“… it was no political accident that Richard Nixon invited Trifa to the Senate. It seemed more than coincidental that Richard Nixon had a rather incriminating history of involvement with another Iron Guardist who had also immigrated to America – Nicolae Malaxa.

“In his June 1941 trial, Viorel Trifa was identified as “commandant of the student Iron Guard corps; he has organized this corps and supplied it with arms.” But it was another trial held that same month which named Trifa’s source for the tanks, guns, and munitions used in the revolt and pogrom. The source was Nicolae Malaxa, the chief contributor to the Iron Guard and the wealthiest man in Rumania, if not all Eastern Europe. Both Trifa and Malaxa were convicted and both shared the same eventual fate – sanctuary in the United States.

“During the 1930s, Malaxa had perceptively invested a sizable loan from the Rumanian government intended for his locomotive factories into other industries, By 1939, he had purchased controlling interests in numerous steel, rubber, munitions, and artillery factories; Malaxa had seen the future of Europe and had realized the next decade’s profits were to be earned from guns, not butter.

“Malaxa, though, was not just a businessman. He also was a political force in Rumanian politics, an agent who actively worked and conspired with the Nazis and the Iron Guard. From his factories, Malaxa hoped, would come the weapons which would win the New Order.

“In 1936, Malaxa went to Berlin to meet with Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering and the two men parted as business partners. This personal agreement became formalized in the 1940 Wohlstadt Pact which integrated Malaxa’s industries with Germany’s. Directing this new Nazi industrial coalition were Nicolae Malaxa and Albert Goering, younger brother of the Reichsmarschall.

“Malaxa’s partnership with the Nazis also intruded into domestic Romanian politics with his staunch support for the Iron Guard. A telegram sent on January 8, 1941, by the German minister in Ruwallin to the Foreign Ministry in Berlin accurately documents the financier’s relationship with the Guardists: “In this fight between the General [Antonescu] and the legionnaire command, one man plays a role who even earlier played a secret part in Rumanian politics: … the present financial mainstay of the legionnaires, N. Malaxa. The legionaires let the clever, big industrialist finance them. He has in his plants the leader of the legionnaire labor organization, Ganeu, and their green flags flutter above his factories…. Malaxa has even again supplied with arms the legionnaire police…. ” Just two weeks after this secret diplomatic telegram was sent, the Iron Guard revolt broke out, and Malaxa’s complicity became even more conspicuous: His house served as the Bucharest Guard headquarters and munitions depot.

“Malaxa, however, was more successful in business than politics, and after the revolt failed he was convicted and jailed by the Antonescu government. He remained in jail for only six months and, under pressure from the Nazis, the Rumanian officials were forced to begin returning Malaxa’s industrial properties. By April 1945, all of Malaxa’s holdings were restored.

“With the defeat of the Nazis, the adaptive Malaxa was ready to make new alliances. Grady McClaussen, head of the American Office or Strategic Services (OSS) in Rumania, signed personal contracts and became an employee of Malaxa’s while still stationed in Rumania as an agent of the OSS. These contracts stipulated that McClaussen would be paid certain sums once Malaxa arrived in the United Slates. Ten years after these contracts were signed, immigration officials would argue that these agreements were actually bribes: money to be paid to the OSS agent if McClaussen got Malaxa into the United States.

“Malaxa’s dealing with the OSS did not preclude, however, his making similar overtures to the Russians. For reasons never disclosed, the Communist government of Rumania in April 1945, issued decree without precedent: Malaxa received $2,460,000 in American money for steel manufacturing plants which had been appropriated by the new Rumanian government and then given to the Russians as reparation payment.

“But, despite this ability to make unique deals with the Communists, Malaxa remained intent on immigrating to the United States. On September 29, 1946 Malaxa arrived in New York as part of a Rumanian government trade mission. He was never to return to Europe.

“In 1948, Malaxa formally applied for permanent residence in the United States, appealing for admission under the Displaced Persons Act. For the next ten years Malaxa was to fight a legal battle to remain in America – the best legal battle his money could buy. Malaxa’s first step was to claim millions of dollars which had been deposited before the war in the Chase National Bank in the name of one of his corporations. These funds had been frozen as enemy assets during the war by John Pehle of the Treasury Department. Normally, such funds are used for postwar compensation to American companies (such as Standard Oil) which had property confiscated by Rumania. However, John Pehle had since returned to private practice and Malaxa shrewdly hired the law firm of Pehle and Loesser to argue his case. This time, Pehle and Malaxa won.

“Similarly, Ugo Carusi was United States Immigration commissioner when Malaxa first attempted to enter as a displaced person. When Carusi resigned his job, Malaxa hired him. Other former government officials and their associates were recruited – and compensated – to assist in Malaxa’s legal suits: Secretary of State John Foster Dulles’s law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell; former Air Force Secretary Thomas K. Finletter’s law firm; and the firm of former Undersecretary of State Adolph A. Berle, who personally testified on Malaxa’s behalf before a Congressional Subcommittee on Immigration.

“The briefs of these lawyers, though, were no match for the vivid eyewitness testimony detailing Iron Guard atrocities which were heard at every Immigration hearing. A victim of justice, Malaxa tried, instead, privilege. At Malaxa’s urging, the junior senator from California, Richard Nixon, introduced a private bill in 1951 which would allow Malaxa to remain permanently in the United States. Congressman Emanuel Celler, head of the House Immigration Committee later said on television, “I saw something suspicious about the bill … I held up the bill.”

“The bill was never passed. The bill was defeated, but it was not the end of Nixon’s involvement with Malaxa. The Rumanian (or one of his lawyers or advisors) now had new scheme. In May 1951, at the height of the Korean War when all industry was under war-time control, Malaxa organized the Western Tube Corporation. The company, of which Malaxa was treasurer and sole stock owner – a thousand dollars worth – planned to manufacture seamless tubes for oil refining. Athough most similar manufacturing was done in the East, Malaxa’s plan was to construct facilities on the West Coast, near the California oil fieIds. It had taken Malaxa five years in the United States to locate what he insisted was the perfect site for new industry – a small suburb east of Los Angeles, Whittier, California. And for Malaxa’s purposes, the site was perfect. It was, coincidentally, the hometown of the then junior senator from California, Richard Nixon. This was, for Malaxa’s purposes, just the first of many perfect coincidences.

“Western Tube’s California address was 607 Bank of America Building, Whittier. This was the same address as that of the law firm Bewley, Kroop & Nixon. Throughout his Senate career, Nixon’s name remained part of the official firm title and Nixon used the office on his vacations in California.

“Thoma Bewley, Nixon’s long-time friend and law partner, was secretary of Western Tube.

“Herman L. Perry, the vice president of Western Tube, was an old Nixon political supporter, the same “family friend” whom Pat Nixon credited as the man who “got Dick … to oppose Congressman Jerry Voorhis.”

“On May 17, 1951, the Western Tube Corporation filed for a “certificate of necessity” to give top war-time priority to its materials and personnel. Also, the company filed a petition seeking “first preference quota” for its treasurer, Nicolae Malaxa, on the grounds that he was indispensable to the operation of Western Tube. These two applications were personally promoted by Senator Nixon. Nixon telephoned the executive assistant to INS Commisioner James Hennessy to plead for Malaxa’s permanent entry. And a letter sent by Nixon to the Defense Production Administrator marked “Urgent” insisted, “It is important strategically and economically, both for California and the entire United States, that a plant for the manufacturing of seamlees tubing for oil wells be erected … urge that every consideration it may merit be given to the pending application.”

“Both appeals were successful. The application for Western Tube was quickly approved and on September 26, 1953, Malaxa was admitted from Canada under a special first-preference petition as a permanent resident.

“Yet, once Malaxa obtained permanent residence in the United States, nothing further was ever done to make Western Tube a reality. Neither Malaxa nor Nixon nor any of the corporation’s other sponsors ever again concerned themselves with Western Tube. Congressman John Shelley of California was later to observe, “It is impossible to discover any reasons for creating Western Tube and seeking a certificate of necessity other than to give Malaxa a springboard for entry into the United States.”

“A year after becoming a permanent resident, Malaxa visited with Juan Peron in Argentina. Malaxa also met in Buenos Aires, according to the CIA, with Otto Skorzeny, the Nazi parachutist who had rescued Mussolini in 1943. Skorzeny, now settled in Madrid, remained a close associate of other Rumanian exiles, including Horia Sima, the head of the Iron Guard.

“When, ten months later, Malaxa attempted to re-enter the United States, he was challenged once more by the INS. In 1958, after two years in the courtroom, Hearing Officer Arnold Martin ruled against Malaxa and ordered him deported. Malaxa appealed the decision and won. Another Nixon friend, U.S. Attorney General William Rogers, affirmed the Immigration Appeals Board’s ruling. “How interesting,” Congressman Shelley noted with judicious understatement, “that this man … found sanctuary in the United States thanks to the special favors accorded him by Mr. Nixon and Mr. Rogers. This was at a time when thousands of deserving displaced persons, victims of Mr. Malaxa’s Nazis, Iron Guardists, and Communists, were unable to obtain admission. Maybe they would have done better if they transported plunder and been friendly enough with Richard Nixon to obtain his personal intervention in their behalf.”

Kris Millegan, March 16, 2011

to be continued …

Watergate Exposed is available at TrineDay, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, The Book Depository, and Books-a-Million.