Royal Vengeance: The Assassination of Princess Diana and the Ancient Royal Cult of Human Sacrifice: Introduction

INTRODUCTION

Spoon-Fed?

Do you swallow the history you are fed?

Do you really believe that scores of British nobles in the prime of their youth, at the height of their beauty and fertility, would just willingly walk to the scaffold, place their head upon a chopping block, and let their heads be whacked off without a fight, without even protest, simply because they were guilty as charged of crimes that were clearly flimsy pretexts?

Or do you question the history you are fed?

Royal Vengeance: The Assassination of Princess Diana And the Royal Cult of Human Sacrifice is the secret history of the British royal family and the nobles and aristocrats who support it. Royal Vengeance is about how the royal family has survived for centuries, and certainly flourished, within an ancient framework of war, religion, sex, mysticism, magic and ritual murder wherein the monarch, its most prominent and powerful member, is considered divine – a god or goddess incarnate. But even though divine, the British kings did not live forever, nor did they even live quietly. Ancient tradition decreed that the divine king would have to die by murder as his own fertility ebbed so that, while still virile and vital, his blood could nourish the earth, unless a suitable substitute victim was killed in his stead. While Princess Diana was the Royal Family’s best-known victim in modern times, she was far from its first, and certainly will not be its last.

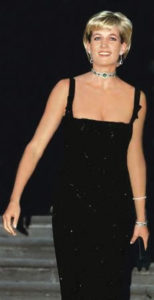

But for now – for us alive today – Diana is the one we know best.

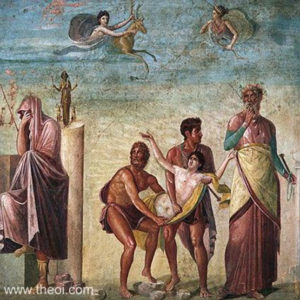

Princess Diana was the most powerful archetype of our age, stirring in our psyches what we recognized to be the never-ending story – a story locked deeply into our most interior, subconscious recesses. The god or goddess comes to earth, assumes mortal form, and is then killed at the height of his or her beauty and effervescence so that the world’s fertility is enhanced and life will continue. Her blood falls upon the ground. Through Diana’s untimely, violent death, we experienced a rare primeval pain that goes back centuries in time, to the earliest days of the first goddess. Through the mixed blessing of a world-wide instantaneous media, all of humanity was able to experience Princess Diana’s life and death.

In older days, holy doves or fleet-winged angels would have broadcast the news abroad. Or else, others would have learned of the divine royal’s death in dreams. Over decades and centuries, the stories would be told and re-told. Princes and kings would change into gods and then change back again, but more divine, more holy than before.

Princess Diana was not just whimsically and coincidentally named for the goddess of hunting, as her brother suggested at her funeral. Diana was the goddess. The entire world was quick to recognize her divine, goddess nature and respond to it. The world watched her every move, and her death in Paris shook the world as fiercely as the destruction of Artemis’s temple at Ephesus centuries earlier.

Some scholars posited that there has only ever been just one god and only one goddess, each with many different aspects that appear as though there is a pantheon. Other cultures, such as Greece and Rome, lived deeply by the Pantheon and easily appropriated gods and goddesses from other cultures – recognizing them as their own divinities. But earlier times needed only these two. Some called them “Isis” and “Serapis,” a combination of Osiris, Isis’s brother-husband, the dying king, and Apis, the ancient bull god. Serapis, even though dying as Osiris, was worshiped as a god of healing and fertility. In his famed cult statue at Alexandria, Serapis was seated on a throne. His head held a bushel of wheat, the heads heavy with grain. His right hand rested on Cerberus, the three-headed hound of the Gates of Death), while his left hand held aloft a king’s scepter, indicating clearly the link between the dying king (heading down) and the fertility and abundance upon which life in the living world depended (heading up). Isis called herself “the mistress of every land” and “she that is called goddess by women.” In Alexandria, their temple was built overlooking the sea. Elsewhere, their temples had aquatic flows or pools of water signifying holy rivers and streams. But they are both even older.

Call them “He” and “She.”

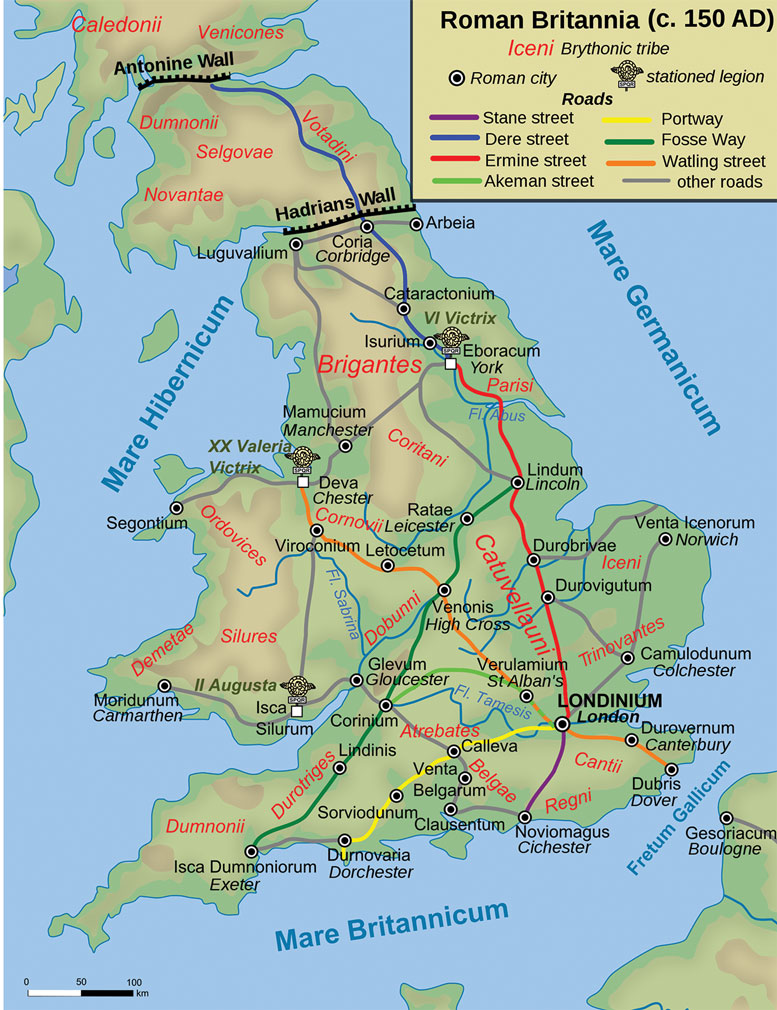

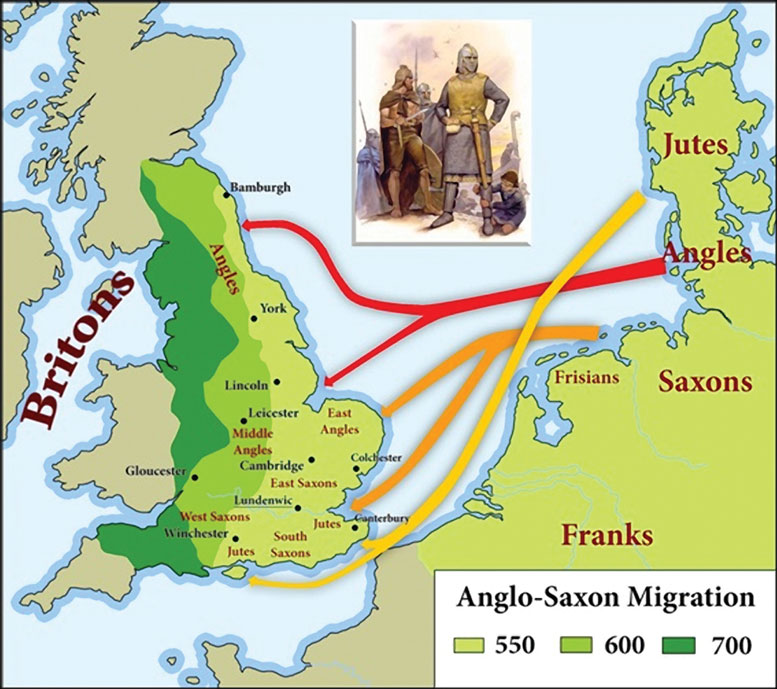

In Britain, long before the Romans and other invaders came, He and She reigned through holy rivers and streams, wells, tree groves, forests, valleys, deep mines and rolling hills. The invading Romans recognized the British gods and their myriad holy places, and made them their own, as well as bringing their own gods into the mix. Invading Saxons, Angles, Jutes, Vikings, and raiders of all kinds mixed in through the centuries, but the gods remained, as did the kings who ruled divinely. Christianity changed very little of this system except to incorporate gods and divine kings into a rather more organized system of saints and martyrs that was itself mostly a retelling of far more ancient tales.

But to give the royal family its due, they did not plan to murder Princess Diana – not in the beginning. She was to be their own living goddess – the young goddess, golden and shining, reflecting the Apollo-like splendor of the family’s eldest prince, Charles, but also providing a more youthful goddess-like reflection of the queen, Elizabeth I. Diana’s role was to give birth to the next generation of royals and to later become queen consort to Charles’s kingship. As the reigning monarch, Elizabeth was aging into a recognizable personification of the Great Mother – the older goddess, Cybele, who ruled over all the gods, and could be terrifying in aspect.

Terrifying. Cruel. Murderous. Needful of blood.

Who imagined in 1981, when Lady Diana married Prince Charles, that her own luminous transcendence would so effortlessly usurp the Mother-Queen herself, as well as every member of the Mother-Queen’s family?

In arranging Princess Diana’s death (in a contrived car crash, her survival of which necessitated killing her in the ambulance by intentionally delaying her arrival to hospital), the royal family was responding with an ancient practice to a modern situation. For them, it was a case of “kill or be killed.” Presented this way, killing Princess Diana was an easy choice for the Royals to make, but it was not all up to them. To put their plan into operation, they needed the approval and assistance of a group Royal Vengeance identifies as the Inner Secret Circle of influential courtiers, officials at the highest government echelons, and power-brokers who surround the monarchy, and who are sworn to perpetuate it – even through the ritual murders of its most beloved and powerful members.

The ancient primitive pattern Royal Vengeance discloses is a simple one: The Divine King (or more rarely, Queen) must be sacrificially killed after a reign-cycle of some years, or else procure a Substitute Victim to die in the monarch’s place. Such a Victim cannot be just any ordinary person, but must possess the qualities, or similar qualities, that set the monarch apart from the rest of humanity as a royal personage. Most importantly, the Substitute must also be a high-status person of a royal lineage similar to the monarch. They may be either royal by blood or by marriage, or they may be a “Prince of the Church,” usually a bishop or archbishop, or other high-ranking official, because their death, even though a substitute for that of the monarch, must have equal or comparable significance; and their blood must fall upon the ground, or something closely connected to the ground, for at its heart (literally), this is a chthonic cult of fertility.

While in older times the most common method of conducting the sacrifice was by decapitation, often on the battlefield, the manner in which the murder is accomplished is not as important as the prime element – that the blood of the Divine King or his Substitute must be spilled upon the ground, or something closely connected to the ground. This spilling of blood was believed to awaken the most powerful forces of all creation – indeed, even depictions of Jesus’s crucifixion show his blood flowing from his body into the ground below.

The death of the Divine King or Substitute has always stirred the following reaction amongst the monarch’s subjects: Great sorrow and unrelenting public lamenting, followed by supernatural apparitions and events, reports of miracles and healings, the creation of temporary shrines, either in the streets, at particular spots or in churches, the construction and more permanent dedication of a memorial, and finally, in many cases, the declaration by the Christian Church that the person killed has become a martyr and, in many cases, has progressed to sainthood, which Royal Vengeance proposes is and always has been an easily recognized pantheon of gods.

Princess Diana’s death followed this ancient English pattern exactly.

Even when the monarch or Substitute is not particularly popular, in and through their death and the flowing of their blood upon the earth, they become instantly beloved, mourned and venerated.  The great public outpouring of mourning and grief following Princess Diana’s death has been much discussed by sociologists and psychiatrists, but one has only to look at the earliest of English history to see that the public’s reaction to Diana’s death was not historically exceptional, and in fact followed a very standard and predictable pattern – although one jarring to modern sensibilities where religion has lost its way. But the public’s grief at Diana’s death only seemed unremitting and permanent; the recent and renewed public expression of love and approval of Queen Elizabeth (as seen at her recent her recent Diamond Jubilee

The great public outpouring of mourning and grief following Princess Diana’s death has been much discussed by sociologists and psychiatrists, but one has only to look at the earliest of English history to see that the public’s reaction to Diana’s death was not historically exceptional, and in fact followed a very standard and predictable pattern – although one jarring to modern sensibilities where religion has lost its way. But the public’s grief at Diana’s death only seemed unremitting and permanent; the recent and renewed public expression of love and approval of Queen Elizabeth (as seen at her recent her recent Diamond Jubilee and 90th birthday celebrations) is proof that the British public subliminally, and with a full collective unconscious, accepted Diana’s sacrifice and soon plunged happily into a new royal cycle.

and 90th birthday celebrations) is proof that the British public subliminally, and with a full collective unconscious, accepted Diana’s sacrifice and soon plunged happily into a new royal cycle.

This practice of killing the Divine King or his Substitute Victim every decade or so stems from an ancient fertility cult that is well-documented in Great Britain, but not widely well-known or understood, and goes unrecognized largely because it is deliberately occluded. In part, it existed in Britain from the time of the first humans there (14,700 years or more ago), who (archaeological evidence shows) practiced human sacrifices and rites, such as drinking the blood of victims from cups made from their skulls, and carried this practice on into the Iron Age – using caves as their cathedrals for religious experience. Later, a whole architecture to re-create the mystery of caves as places of rite and initiation emerged, covering all of Europe, then the Americas and, finally, the world. Britain’s ancient, primitive human sacrifice rites and uses of magic were supplemented by other religions and deities as roaming tribes moved in and out of Britain, bringing with them their own particular gods and goddesses, rites, rituals and sacrificial practices.

When the Roman Army arrived in Gaul and Britain, the Romans found a well-established Druid priesthood that regularly conducted human sacrifices that terrified the Romans (no strangers themselves to the practice of human sacrifice and the concept of divine kingship), but in which the Romans also recognized elements of their own beliefs and practices. These practices became not only more entrenched as Britain faced invasion after invasion of tribes and foreign forces, but they simultaneously and discreetly became fully incorporated into a well-established system of Divine Kingship that soon spread across Britain, which was then composed of various diverse kingdoms – all subject to foreign invasions by peoples who also practiced some form of human sacrifice – and thus united in their diversity by similar beliefs and practices that were considered fundamental to humanity’s continued existence and well-being.

If the ground were not regularly sprinkled with the blood of the Divine King, the crops would not grow, the rain would not fall, cattle would die, and children would not be born.

Although initially in conflict with early Christianity coming from Rome, the system of divine sacrifice fit well with the Church’s own established internal system of martyrdom, and these two disparate systems were soon working in tandem. The result was an exotic, very idiosyncratic and unique form of Christianity that combined with pre-existing paganism – a paganism that was a hardy survivor. Rome despaired of completely curing Celtic Christianity of its pagan habits for many centuries before finally giving up (or being forced to give up), even as the Roman Church dealt with royal houses all across Europe with similar practices. In the 16th century, England’s boldest and bloodiest Tudor king, Henry VIII, made himself the Supreme Ruler of the New Religion (British or Celtic Christianity) which evolved into the State Church, or the Church of England – a title later reduced, for Henry’s daughter and sole surviving heir, Queen Elizabeth I, to the less dramatic but still all-powerful title of Supreme Governor. By the time of the Tudors, the actual power wielded by the monarch had grown exponentially, but was largely hidden from public view under the veil of numerous advisors (who also grew in power but who were held almost completely in check by the cyclic cult of sacrifice). As a result, paganism in Britain – the true “Old Religion”– was never fully wiped out, although the emergence of Parliament as a political force, the execution of James I’s son, Charles I (who publicly contended with Parliament that he was a Divine King and a god), the years of Cromwell’s rule, the threatened execution and forced exile to France of James II of England and VII of Scotland (who, like his father, Charles I, and James I and VI, publicly declared that he was a Divine King), and the seventeenth-century witch trials all pushed Celtic paganism and the Old Religion further underground.

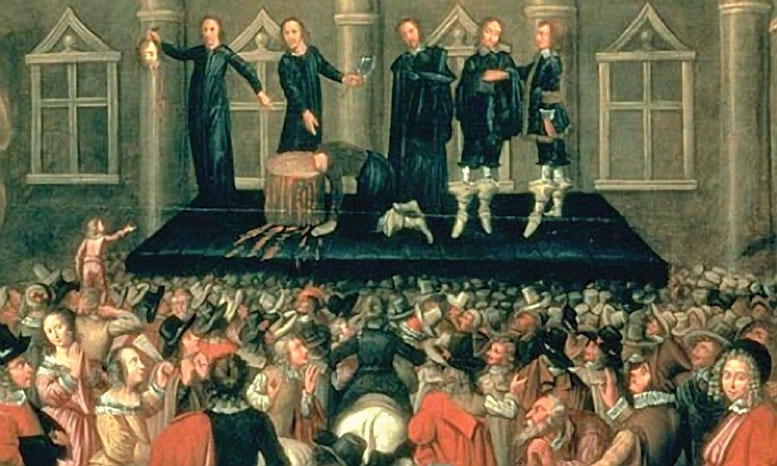

Even the English Army’s explanation for Charles I’s execution was curiously cryptic: that the Army “had come to understand ‘that the Lord’s purpose was to deal with the late King as a man of blood,’ and, electrified by this revelation, ‘we were extraordinarily carried forth to desire Justice upon the King, that man of blood.’” Charles’s “blood” became enshrined in its own feast day as “State Services” for January 30th included this reference to the “Blood King,” along with a prayer for the end of vengeance:

Being the Day of the Martyrdom of the Blessed King CHARLES the First; To implore the mercy of God, that neither the Guilt of that sacred and innocent Blood, nor those other sins, by which God was provoked to deliver up both us and our King into the hands of cruel and unreasonable men, may at any time be visited upon us or our posterity.

Charles I’s bloody shirt (a waistcoat), clothes from his decapitation, and other relics are kept today not only in churches but in the Museum of London, Albert & Victoria Museum, and other secular places, even though the original plan was to place Charles’s relics in shrines and create a church-based cult of the martyred dying king. Although controversy exists over whether there’s an adequate chain of custody for authenticity and whether all the clothing pieces were actually Charles’s, they are splattered with blood and still regarded as valuable relics. John Weesop was an eyewitness to Charles’s execution and famously painted what he saw – not Charles before the moment of execution but Charles just moments after his head was cut off. In Weesop’s painting, Charles’s bloody neck still lies on the block while a man holds Charles’s severed head aloft to the crowd. Blood flows down from the head and from the neck on the block, showing several bits of flesh and pools of blood, to which people in the front are gesturing excitedly to mop up with handkerchiefs (in the belief that royal blood was healing and miraculous). So great was popular demand for Charles’s blood that even the chopping block “was cut into small pieces, and large sums of money were offered for a lock of his hair, or a few grains of sand which had been discoloured by his blood.”

Charles I was canonized as a saint and martyr on May 19, 1660 – the last created saint of the Church of England. His feast day was designated as January 30 – the date of his execution in 1649. Today, his blood cult is small but still exists despite the Church “unjustly remov[ing] him from the Kalendar of The Prayer Book” in 1849. Charles’s execution by “decollation” remains a scholastic source of controversy between ideas of the sacrifice of a divine king and the more political crime of regicide. However, throughout his trial, Charles was presented to an increasingly distressed British populace as “a symbol of suffering kingship.” And even though mainstream historians focus fiercely upon “the repeated upheavals of the period, a political theology based upon patriarchalism and divine right [of kings] remained relevant and resilient amongst large sections of the community well into the eighteenth century.”

Royal Vengeance argues that that this blood cult of divine kingship survived even longer, and still exists today.

More than royalty was restored restored when Charles I’s eldest surviving son, Charles II (officially childless but the father of many bastards) was brought back to reign. A mere eleven years after Charles I was decapitated, Charles II went roundly after John Cook, the anti-royalist barrister who prosecuted his father. Found guilty of regicide, after a trial that modernists consider to have been “outrageously rigged,” Cook was hanged, drawn and quartered – a punishment reserved for high treason, but one which also followed in the footsteps of the ancient pagan practice of dismembering kings and then distributing their body parts throughout the kingdom. Cook (along with some of his co-regicides) was rent asunder at Charing Cross, a place where the Saxons noticed that the Thames River turned to a 90-degree bend (from the Saxon word “bend,” or “cierring”). The place at the Thames, a sacred river personified by a male god usually shown hunting, had been marked between 1291 and 1294 by an

Eleanor Cross, which Parliament destroyed in 1647. During the Restoration, Charles II replaced the demolished Cross with a statue of Charles I astride a great horse, although a subsequent Eleanor Cross was later erected nearby by Queen Victoria. All of this will be explained in Royal Vengeance. At this early point, however, it is enough to note that the free-standing crosses that so mark the British landscape everywhere (especially following the end of World War I) were remnants of an earlier pagan worship of a single tree or wooden pole, a totem held to represent a god. When Charles II marked the spot with his executed father’s statue, he was making an important point: The Divine Kingship of England continued. But he wanted to make the point by publicly showing the larger-than-life body of the god himself – the god who had died by shedding his blood, which had fallen upon the land. The physical person of the king represented the vital link between the secular, or earthly, and the divine, just as the holy trees of Druidism linked earth and sky. And Charles II placed the statue of his murdered father in the virtual center of London – the point from which all distances from the capital are measured.

Like generations of pagan kings long before him Charles II deliberately changed not only the landscape, but public perceptions of that landscape.

Although the English Civil War may have briefly ended the rule of the House of Lords, it did not destroy the Divine Right of Kings. Charles I was killed not by democracy, but by Oliver Cromwell, who “was at that time the ruler in fact though not in name, and though uncrowned and unanointed,” To make the point that Cromwell was king in fact, Parliament brought the Coronation Chair of King Edward I (which was made in 1300 and contained the sacred Stone of Scone) from Westminster Abbey (where almost all English kings are crowned) to Westminster Hall so that Cromwell, dressed in an ermine-lined robe of purple velvet (the exclusive color of kings), could sit in it (under a canopy of state) and hold a golden scepter during his “installation” as “Lord Protector” of the realm. Underlings routinely referred to Cromwell as “His Highness” – with only the “Royal” word of the tradition being dropped. Charles I was not only the divine king, but he was Cromwell’s divine substitute sacrifice. To underscore this particular point, when Cromwell died on September 3, 1658, he’d already prearranged his own funeral – a lavish spectacle modeled on the funeral of the late King James (the decapitated Charles I’s brother). So complicated were the arrangements that the people orchestrating it needed so much time – two long months – that Cromwell’s body began to decompose and stink horribly. The Lord Protector’s body was then interred quietly, without any public participation, so that the actual date of burial is still disputed by historians. However, this was remedied by creating a fake body for the man who was not a king in name but a king in fact. An empty casket was topped with a life-like effigy of Cromwell robed in purple velvet, gold lace trim and ermines. In its right hand was a scepter and in its left, the globe of the world; a crown rested on a cushion near to it. More serious, however, was the rumor that Cromwell had not died at all, or perhaps, had died and come back to life, like Osiris, because of the long delay in having the funeral, and because of the grandness of his effigy, which was paraded before huge crowds in the streets on the way to Westminster Abbey.

On July 30, 1661 (the twelfth anniversary of Charles I’s execution), Royalists dug up Cromwell’s corpse (which had originally been buried, like many English kings, in Westminster Abbey), hung the dead body in chains at Tyburn’s gallows, and then ceremoniously beheaded it. Cromwell’s body was then kicked into a pit at the foot of the scaffold, and his decapitated head was put on a pole and publicly displayed at Westminster Hall – where Charles I had been tried and condemned – until 1685 – an astounding twenty-four years, after which time, Cromwell’s head was said to have been stolen and then privately sold to numerous sequential owners and was sometimes put on public display. Finally, Cromwell’s head (or at least the head believed to be Cromwell’s) was buried underneath the floor at Cambridge’s Sidney Sussex College – where Cromwell had briefly been a student. The rest of Cromwell was also dug up and re-interred under Westminster Abbey’s Guards Chapel’s floor. These floor tombs are a far cry from the grandeur of Cromwell’s original monumental tomb, set in the western wall of the Henry VII chapel (the “Lady Chapel”) amongst anointed kings and queens, including numerous Tudors, Elizabeth I, and Mary Queen of Scots. Cromwell’s original tomb (before its violation and destruction) was described as being made of costly marble and alabaster “surmounted by an effigy of him reclining, dressed in royal robes, a scepter in one hand, a globe in the other, and a crown on the head.”

Cromwell’s postmortem decapitation was no less vivid a sacrificial rite of divine kingship than any living monarch’s.

After the heirless Charles II’s death, the throne passed to his younger brother, the staunchly Roman Catholic James II. The Throne going to James II’s eldest child, the thoroughly Anglican Mary and her thoroughly Protestant husband, William of Orange, forced the Old Religion far into the shadows. But when William and Mary died childless, the throne went to Mary’s sister, Anne, and her Lutheran husband, Prince George of Denmark. As the British monarchy then foundered anew into a crisis on issues of fertility (including Queen Anne’s failure to provide a surviving heir despite no fewer than seventeen pregnancies and five live births), the Old Religion and its royal practice of Divine Kingship were kept utterly secret, but were still known within the monarch’s inner secret circle, and still powerful. This led to increased control over the Divine Kingship system by the most powerful members of the various circles such as the Noble Order of the Garter, Order of Bath, Order of St. Michael and St. George, the intelligence agencies, and the whole aristocratic system – including elite royal assistants called “courtiers.” Individuals from these more “open” and publicly-known groups formed their own group, the Inner Secret Circle, which was closest to the monarch and the royal family (although not necessarily by the family’s choice), and became directly responsible for ensuring coronations of those chosen, and also carrying out assassinations and, in some instances, “mock” assassinations of Divine Monarchs, but mostly of their Substitutes – especially in cases where the monarch, king or queen, had become exceptionally popular, or served some other valuable purpose to the Circle. However, the Circle also selected Substitutes on the basis of safeguarding the overall institution of British monarchy in general.

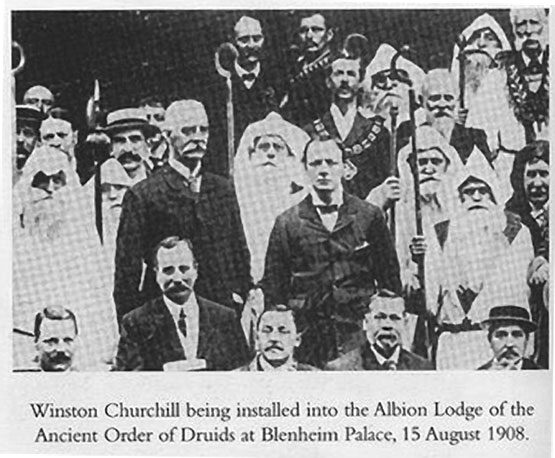

England’s present queen, Elizabeth II, fully but discreetly acknowledged the Old Religion’s survival when she formally and publicly joined its ranks, just prior to her marriage to Prince Philip in 1947, who was also initiated into the Welsh Gorsed of Bards – a revived Society of Druids – as memorialized in little-seen films and photographs located in Life magazine’s and Pathe’s archives. “Gorsed” itself derives from the Welsh word for “throne.” Its symbol, the Awen, represents the Divine Sun. Elizabeth’s parents, as the Duke and duchess of York, had both been previously initiated into Druidism as well. No less a personage than Sir Winston Churchill was inducted on August 15, 1908 into one of the Gorsed’s branch cults, the Albion Lodge of the Ancient and Archaeological Order of Druids at Blenhiem Palace – Churchill’s own family home. To support paganism’s deep and persistent roots in the Church of England, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, also joined. Both the future queen, her consort, and her foremost archbishop (A Wales native named for the Rowan, a tree particularly sacred to the Druids) donned the robes and headdresses of the Druid priesthood, and took vows in a sacred grove in the middle of a circle of Standing Stones before the modern Druids’ high priest.

The Anglican Archbishop’s conversion to paganism did not pass unnoticed. The Guardian newspaper reported quoted The Rev. Angus Macleay, of the evangelical group, Reform, as saying: “Even if to Welsh speakers it is recognised as purely a cultural thing, the appearance of it looks very pagan. You have folks calling themselves [D]ruids, dressed in white and going into a stone circle, reciting prayers which don’t mention Jesus Christ.” In fact, Rowan Williams was not yet fully invested in the Anglican Church’s highest office before becoming a Druid first.

But British monarchs, if they pay lip-service to modern Anglicanism, are free to practice any kind of religion they want in absolute secrecy. They need not attend public “mainstream” Anglican religious services, although they occasionally do, especially for crowd-pleasing royal weddings and the somber yet spectacular royal funerals. Secrecy has been assured for centuries because the churches where Queen Elizabeth herself attends are her very own personal property (and the property of every monarch). These are called “Royal Peculiars,” and and certain aspects of their interiors (such as the Roman Cosmati mosaics of Westminster Abbey installed in the 1260s under Henry III, which reflect not traditional religious scenes but instead cover the floor with brilliant explosions of color portraying the Pleiades and other “star” systems as well as other complex allegorical  patterns and encrypted messages and an end-of-the-world prophecy (not Biblical per se, but determined by the lives of ravens, whales, stags, dogs, horses, and other animals, several of which are totem animals of Mithraism) by way of inlaid stone, gems, brass and colored glass, both clear and opaque, and the pronounced use of purple porphyry, a “royal” or “imperial” stone mined in Egypt from pharaonic times. The green stones used had been originally mined in Sparta; yellow marble from Tunisia, pink beccia giallo, black Egyptian Gabbro, alabaster and Purbeck limestone were all inlaid by hand.

patterns and encrypted messages and an end-of-the-world prophecy (not Biblical per se, but determined by the lives of ravens, whales, stags, dogs, horses, and other animals, several of which are totem animals of Mithraism) by way of inlaid stone, gems, brass and colored glass, both clear and opaque, and the pronounced use of purple porphyry, a “royal” or “imperial” stone mined in Egypt from pharaonic times. The green stones used had been originally mined in Sparta; yellow marble from Tunisia, pink beccia giallo, black Egyptian Gabbro, alabaster and Purbeck limestone were all inlaid by hand.

All this swirling, dervish-whirling patterned esotericism, spilling into an abstraction that has no clear relationship to any mosaic art that came before it, lies before the Abbey’s high altar. Curiously, for centuries, most of the time, the Cosmati floor of Westminster Abbey was kept covered – hidden from sight. It was not even uncovered for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation. The reasons are unclear – did someone merely forget that the spectacular Cosmati Pavement had ever been created? It’s unlikely, given that the same materials and same artisans who constructed the Pavement also used the mystical mosaic materials and designs to decorate the nearby tomb and shrine of St. Edward the Confessor in the Abbey. Perhaps insight can be gained by looking to archaeology. Prior to writing her popular works on the British royal family, kingship and paganism, the Egyptologist Margaret A. Murray helped uncover in Egypt a secret chamber that turned out to be a temple dedicated to Osiris, as well as a place for celebration of various mysteries. Murray and her team of archaeologists found the entrances to the Osirian temple filled with trash from Roman times – deliberately left behind in order to block future access. It is thought that the Romans would have noted valuable stones during their own initiation ceremonies at the temple, and perhaps even dug out and removed items such as prized porphyry and parts of stone floors from these temples.

Some pieces of Westminster Abbey’s Cosmati Pavement, for example, for example, are thought to be many thousands of years old in their own right, and were salvaged from such earlier, non-Christian sites from places like Middle East, North African, and Mediterranean pagan world. But the use of trash and debris to clog the entrance may have another, more profound, purpose, the meaning of which escapes our understanding today because so little is known of mystery cults. For example, archaeologists have long noted that Mithraic temples are often found filled with such debris that is itself very ancient – sometimes even older than the temple itself. The Mithraic temple lying beneath the Christian church of Santa Prisca in Rome was found to have been deliberately stuffed with bricks, broken bottles, and dirt and debris taken from a nearby graveyard. Some of this trashing was originally thought to have been done by angry Christians, who did indeed sometimes invade nearby Mithraiums and topple and deface cult statues, even dragging out pieces of masonry which eventually found its way into nearby churches, homes, and even street curbs, some of which can still be seen today, littering the Aventine. However, some archaeologists theorize that using trash and debris to block ancient religious temples had a different meaning, especially in the use of graveyard debris. As Marleen Martens noted, “[t]he act of burying large quantities of things in the ground is not necessarily a matter of getting rid of ‘rubbish,’ holy or not, but may in its own right be a means of communication with the Other World and an expression of the desire to devote the memory of the event to the gods.”

It is speculation but perhaps, by placing the Cosmati symbols nearest to Westminster Abbey’s high altar in the floor, a group like the Inner Secret Circle was surreptitiously attempting to do something similar – to honor the gods below – the chthonic powers – while also appearing to worship the more traditional God above. In times of Christian conservatism, the Cosmati floor could be covered with wood and carpet, and hidden away, awaiting days of more open propitiation, of which the funeral of Princess Diana before the Cosmati floor is but one example. Intriguingly, at no time did Princess Diana’s coffin touch the Cosmati Pavement; it rested on the Masonic black-and-white checkerboard part of the Abbey’s floor. In order to reach the Cosmati Pavement, one must ascend a flight of five stairs – a short climb that was made in 2011 when Prince William married Kate Middleton on top of the Cosmati Pavement. These are pronounced pagan Old Religion elements not found in a normal Anglican Church.

Princess Diana, killed after a Paris car crash in 1997, was only the latest Substitute Victim in a long history whose origins lie far deeper in the ancient populations of the Mediterranean, Persia, Asia and North Africa. Although some say it was Princess Diana’s death that caused the royal family to enter into a crisis of public confidence, its “crisis” had begun long before 1997. However, by that year, so many pressures had come to bear upon the royals that killing Princess Diana not only fulfilled the ancient need to produce a Divine Sacrifice so that Queen Elizabeth II could continue to reign, but it also solved many other problems for the family that had suddenly converged upon it over a period of years, and then came to a crescendo with Princess Diana’s determination to promote a global ban on land mines– for which she was poised to be awarded the enormously prestigious 1997 Nobel Peace Prize.  Winning the Nobel so proximately to her divorce from the Queen’s heir apparent, and after being so painfully publicly stripped of her “Royal Highness” title, would have dealt a death blow to Prince Charles’s already shaky popularity in the Royal Succession (not to mention an equally fatal blow to the royal family’s popularity). And although Charles championed worthy causes like urban blight, homeopathic medicine and organic farming, none of these stirred the public as Diana’s far more dramatic causes of AIDS and banning land mines had. But the Nobel Prize is not awarded to anyone posthumously. Diana’s death ended that real threat to the crown. It also quelled the fears of the United States government about the far-reaching powers Diana might have to affect this particular aspect of warfare. Subsequently, the Nobel Committee awarded the Peace Prize jointly to Diana’s charity the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) and Jody Williams (a young female American anti-land mines activist) “for their work for the banning and clearing of anti-personnel mines.” However, the image of Diana as an international anti-land mines campaigner was so powerful that numerous news outlets incorrectly reported that she’d won the prize a few months prior to her death, or else had been awarded it after.

Winning the Nobel so proximately to her divorce from the Queen’s heir apparent, and after being so painfully publicly stripped of her “Royal Highness” title, would have dealt a death blow to Prince Charles’s already shaky popularity in the Royal Succession (not to mention an equally fatal blow to the royal family’s popularity). And although Charles championed worthy causes like urban blight, homeopathic medicine and organic farming, none of these stirred the public as Diana’s far more dramatic causes of AIDS and banning land mines had. But the Nobel Prize is not awarded to anyone posthumously. Diana’s death ended that real threat to the crown. It also quelled the fears of the United States government about the far-reaching powers Diana might have to affect this particular aspect of warfare. Subsequently, the Nobel Committee awarded the Peace Prize jointly to Diana’s charity the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) and Jody Williams (a young female American anti-land mines activist) “for their work for the banning and clearing of anti-personnel mines.” However, the image of Diana as an international anti-land mines campaigner was so powerful that numerous news outlets incorrectly reported that she’d won the prize a few months prior to her death, or else had been awarded it after.

Then, there was the Henry VIII factor. Under Anglican Church laws as of 1997, Prince Charles’s divorce from Princess Diana, with her still living, would have made it not impossible, but extremely controversial, for him to become the King of England and Supreme Governor of the Church of England (which did not countenance remarriage of divorced persons whose spouses were still living). The issue arose virulently in 1991, when Charles and Diana’s marital rift could no longer be publicly ignored. By 1991, Andrew Morton was planning to publish his tell-all book that presented Princess Diana’s personal story about how the royal family and Prince Charles in particular had viciously mistreated her, and many other similar books were on their way to being printed – although Morton’s was the only one in which Princess Diana herself had secretly collaborated so that Morton’s book was, in effect, her autobiography. But before these best-selling books were serialized in newspapers and hit the stands, there was a growing awareness in the United Kingdom that the Wales’s marriage had hit not just a crisis, but also a constitutional crisis that could jeopardize the monarchy’s survival. In fact the news extensively reported on not only the Gulf War of 1991 in Kuwait, but also on what became known as “the War of the Waleses:”

“In 1991, a newspaper filmed the couple at a few public engagements together and invited psychologists to analyze the couple’s behavior. One psychologist observed, ‘The emotional temperature is very, very cold. There’s nothing there, not even at the most basic level. It seems as if she is trying to cut him out of the picture entirely, to pretend he isn’t there. It’s not the sort of behavior one would expect from a close, happily married couple living normally as man and wife.’ Prior to Diana, the British people (as did the royals themselves) believed that, for “the Prince of Wales and future head of the Church of England, marriage had to be forever. Divorce was impossible, no matter how dire the circumstances. It was a lifetime commitment, and he had to get it right the first time.”

So in 1991 divorce, an ever-growing marital practice among commoners, nobles and aristocrats alike, was still unthinkable for the heir to the throne. Technically, the Queen herself would have to give permission for it; and it seemed unlikely that the sovereign would ever do that because it would jeopardize the succession and Charles’s right to head the Church of England; Charles could appeal to Parliament for a divorce, but that would cause social and political chaos. If he waited until he became king, Charles might find himself in the same situation as did his great uncle, the former Edward VIII, who was forced to abdicate. However, the death of Diana would make a clean break, enabling Charles to become king, become the Church of England’s Supreme Leader, and freely remarry with neither impediment, shadow, nor the constant upstaging and undermining at which Diana was become so skilled. But at the time, experts agreed that a royal divorce was unlikely: “The very notion, splutter[ed] Charles Kidd, editor of Debrett’s Peerage, is ‘distasteful, damaging, irresponsible and offensive.’” Royal biographer, Brian Hoey, agreed: “[Divorce] is not going to happen. The Prince of Wales considers himself to be the rightful successor to the Queen – not only as the sovereign of Britain, but also as the head of the Church of England. And as head of the Church of England, he cannot divorce.”

However, if Diana were dead, Charles could easily take the throne without incident, and perhaps even remarry. He’d become unpopular, true, but so had many kings before him. Diana’s continued existence as an international superstar now divorced from the heir apparent was not only infuriating, but it threatened Charles’s ability to fully succeed his mother without the Church having to undertake significant changes in its own laws. While these changes may well have been eventually undertaken by the Church on its own initiative, without Diana’s death, they would have gone forward in a state of great controversy; nor would Prince Charles have likely been permitted to remarry to anyone, let alone Camilla Parker-Bowles (who was a witting party to Charles’s adultery), and still be crowned king. Initially, this fact had always been Princess Diana’s trump card in her negotiations with the British Royal Family, including her determination to remain legally married to the heir, until two things: The first was the sensational book, Diana: Her True Story, written by Andrew Morton (but with substantial “input” from the Princess) and published in 1992; the second was Princess Diana’s BBC Panorama interview with Martin Bashir in 1995. In Diana: Her True Story, the Princess accused the Royal Family of abusing her, not recognizing her genius, and driving her to attempt suicide numerous times; in Diana’s Panorama interview, the disgruntled princess stated, among numerous other things hateful to the Royal Family, that “the Establishment” who sought to protect Prince Charles and place him on the throne had sought to have her declared mentally unfit and placed in a home; that Prince Charles was unfit to become king; and that Diana wished for their twelve year-old son, Prince William, to be elevated over his father in the line of succession.

Princess Diana, in both her veiled autobiography and in her televised confession, confirmed the existence of the Inner Secret Circle (although she called it “the Establishment” run by “the Grey Men,” likely referring to both the color of hair and suits of royal courtiers). After her death, Mohamed Al Fayed undertook a personal effort to identify the actual persons who constituted the Inner Secret Circle – an effort that fell flat largely because Queen Elizabeth II, Prince Philip and Prince Charles not only refused to testify under oath, but prosecutors themselves steadfastly upheld the royals’ refusal to appear in what were, after all, the Queen’s own courts. However, the public record both before and after Diana’s death is replete with oblique references to these shadowy courtiers, their families, and the deeply secret support system of government agencies that kicks up the dust at any effort to look beneath the surface. We will explore these in detail herein.

There were numerous other factors that Royal Vengeance discusses, but these two – Diana: Her True Story and Princess Diana’s Panorama interview – sealed her fate to die as a Divine Substitute. That the Princess was also the most glittering popular figure of her age only added to her value as a Divine Substitute Victim from an occult point of view. Moreover, at age 36, her fertility would have been waning, although she regularly and deliberately expressed a desire for at least one more child, who she hoped would be a much-longed-for daughter – although now, the father (and step-father to the two princes) would most likely be Dodi Al Fayed, an Egyptian Muslim. Nor was Dodi Diana’s only Muslim lover. Aided by modern technology, Diana could have perhaps borne more children – naturally, or through some other kind of arrangement and, helped by the Al Fayeds’ considerable fortune, created a rival court to completely undermine Prince Charles – who (as the heir apparent) still would have been stifled in his own remarriage plans as long as Diana remained alive. With or without her “HRH” status, Diana would have been free to remarry, especially if she opted out of the Church of England, and did something dramatic like convert to Islam. Her mother, after all, had converted to Catholicism, and Diana had shown an active interest in Islam since her love affair with Oliver Hoare, a collector of Islamic art.

But in July 1995, Princess Diana reached thirty-six years – the same age as Anne Boleyn when Henry VIII had her killed.

When Lord Rees-Mogg, an early Princess Diana supporter, enthusiastically declared her to be a modern-day “‘Joan of Arc,’ heading armies into battle,” he had not yet imagined that Diana would meet an end in France similar to that of Joan, who was burned to death by her Inquisitors. But like Joan, who claimed at trial to converse with visions of St. Michael, St. Catherine, and St. Margaret, Diana said she regularly consulted with the departed and also with spirits. The English declared Joan to be a witch because of her claims, although Margaret Murry reasoned that instead, Joan was the leader of a pagan witch-cult headed by the “incarnate god” that worshipped the goddess Diana. After burning her to death, Joan’s ashes were dumped into the River Seine – the same river along which Princess Diana drove to her death.

Centuries entwined together that night in France. From November 1995 on, the royal family and the Inner Secret Circle simply waited for the opportunity to rid themselves of their troublesome, increasingly dangerous and increasingly unpredictable daughter-in-law, who had started out her young adult life as a golden goddess showing such promise. Once the Inner Secret Circle concurred that the crown would significantly benefit from Diana’s death and a sacrifice was now especially timely, political strings were secretly pulled to put a plan of Divine Substitute sacrifice into place. Princess Diana’s visits to Paris with Dodi, and without her own security, afforded the royal family and its Inner Secret Circle the opportunity they needed to murder her, and spill her blood upon the ground. Charles and Diana had already divorced in 1996 upon the Queen’s personal command, expressed in two separate letters (one each to Charles and Diana), which had suddenly ended Diana’s game – but not fully, because Diana specialized in playing the long game. The Queen’s command to divorce was a twist, but one which was certainly anticipated by Diana. However, Diana did not anticipate the depths to which the Inner Secret Circle would go to ensure Charles’s path to the throne. Divorce would not sufficiently clear Charles’s path to the throne, nor to the woman he loved. To clear that path, Diana had to die.

In Paris, Diana and Dodi went (to paraphrase a comment Diana made about herself at her 1981 royal wedding) like guileless lambs to the slaughter.

The sole survivor of the Alma Tunnel crash, Dodi’s bodyguard, Trevor Rees-Jones, claims he has no memory of events that night. And to others, Rees-Jones has confided that if he remembers anything and talks about it, “they” will murder him. And the rewards that come to those who keep the secrets of the Inner Secret Circle can be rich indeed. But to thwart them is to almost certainly die.

What the British royal family did in arranging Diana’s death was nothing different than what they have done from time immemorial: They kill people, carefully, selectively, inventively and with great purpose. While it is true that a Victim may be selected in order to not only fulfill the periodic seven-year need for the sacrifice of a Divine King but to also solve other problems or issues, the overall periodic need for a human sacrifice can be easily seen by looking both to history and to the turn of modern events. Royal Vengeance looks at numerous deaths of British monarchs and those closest to them, starting from the earliest pre-Saxon and Saxon kings. It builds upon an older thesis of Divine Kingship promoted by classical scholars such as James G. Frazer (The Scapegoat, The Dying God, The Golden Bough) and more controversial writers such as Margaret Alice Murray (The Divine King in England, The God of the Witches, The Witch Cult in Western Europe) whose books have remained perennially popular despite more contemporary reviews disparaging them for their lack of rigor. Royal Vengeance solves some of the problems of rigor, and takes a scholarly yet fresh and easily readable review of very old evidence, records and eyewitness accounts of “royal deaths,” and the trials and executions of royals and persons close to them, and the aftermath of martyrdom, sainthood, the establishment of shrines, and the whole ancient process. Royal Vengeance traces the path of the Divine King from the earliest English rulers to the Saxon kings (the “Os” kings who believed themselves to be descendants of the god Odin), into the Plantagenet, Tudor, and Stuart (Stewart) bloodlines, and then into the more modern royal houses, including the Windsor branch that rules Britain today. Royal Vengeance shows that while not all deaths around the Crown were part of the sacrificial system of Divine Kings, many were. While the modern record is naturally harder to discern because kings no longer have the power to arbitrarily order people to be killed, Royal Vengeance proves that the ancient practice of Divine Kingship and sacrificial Substitutes has persisted into the present day.

Royals and persons close to them die often under very unusual circumstances. These bear exploring.

Readers of Royal Vengeance will be familiar with some names, such as Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, Elizabeth I, Queen Victoria and Elizabeth II, but other names will be completely unfamiliar to most, and hopefully this adds to the reader’s sense of excitement as Royal Vengeance’s story is told – the first book to fully unfold the entire pattern, and trace it back even further to practices well-documented in ancient Greece, Rome and Egypt. Accounts of the deaths of Edmund (whose death was foretold by St. Dunstan, who saw “the devil dancing” but arrived too late to prevent the murder), Edward the Martyr (whose stepmother stabbed him with a dagger while offering him a cup of wine), Earl Waltheof (the only English noble decapitated by William I after his marriage to William’s niece), and William II (the notorious Rufus the Red, felled by a single arrow while hunting the stag in New Forest) are particularly riveting, and show powerful parallels with the deaths of later royals and their retainers (who served as Divine Substitutes). The murder of publicly well-known figures like Thomas Becket (Henry II’s Archbishop of Canterbury, martyred by soldiers of Henry II in Canterbury Cathedral), and the execution of the Scots’ hero, William Wallace, were all mechanisms to provide a Divine Substitute Victim so that the ruling king could continue to live through another reign cycle, while also getting conveniently rid of the crown’s most powerful foes. Other instances of Divine Sacrifices include the murder of Edward II; Edward’s lover, Piers Gaveston; Roger Mortimer (lover of Queen Isabella of France, consort of Edward II); the young Princes in the Tower (King Edward V and his younger brother, Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York); Perkin Warbeck (pretender to the throne); Ralph Walford (pretender to the throne); Earl of Warwick; Anne Boleyn (the executed second wife of Henry VIII); Catherine Howard (the executed fourth wife of Henry VIII); Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (the great English poet and Howard cousin to both Anne and Catherine)– both allegedly executed for high treason, but in reality, both were married by Henry VIII in order to produce male heirs and, when their fertility failed (for Anne, through miscarriages and stillbirths and, in Catherine’s case, no immediate pregnancy) and the king’s fertility was brought into question thereby, they were used as Divine Substitute Victims and executed so that Henry could continue to reign. Their heads were cut off from their bodies and their blood made to fall upon the ground.

In many cases, readers will have already “seen” the “movie story.” But Royal Vengeance now reveals to them the true story.

Royal Vengeance posits that not even Princess Diana understood her own “true story.”

Princess Diana came from the Spencers, a line of British nobles and aristocrats who, like the Howards, have served as a willing source of Divine Substitutes for centuries. England is a quirky place: the royal system is completely closed, whereas the systems of aristocracy and even gentry are more open. Royal marriage has been exceptionally closed until recently, taking only other royals because, as Prince Charles himself once cryptically said, “The advantage to marrying someone royal is that they do know what happens.” Sometimes, very occasionally, the royals’ gate swings open to members from the more open classes. In the fifteenth century, the royals’ gate swung open to welcome the beautiful, sexy and accomplished Boleyns and Howards; centuries later, the royals’ gate swung open again to allow Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon and Lady Diana Spencer – both daughters of earls – to enter. The price of entry into the royals’ closed system of court and unimaginable privilege has been, occasionally, the lives of some of their family members a factor always balanced with the elevation of other family members). For the Howards, the price was excruciatingly high, but the elevation over centuries was worth it – and if one extends the Howard line to Queen Elizabeth I, the Howards’ influence on not just English history but the western world is enormous. So dutiful and reliable were they that even Queen Elizabeth tired of killing them, and instead just held them occasionally in the Tower of London without even signing their death warrants.

Royal Vengeance also traces Diana’s Spencer lineage to that of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother’s Lyon ancestry (and through the Queen Mother to Queen Elizabeth II), and shows that all three royal women descend from the line of a powerful Scottish witch whom King James V of Scotland ordered be burned to death – Janet Douglas, Lady Glamis – who perished in flames on July 17, 1537 while her surviving son was forced to watch. Later scholars’ opinions of Lady Glamis’s innocence substantiate the need of King James for a Divine Substitute, although it is clear that Lady Glamis was herself well-versed in the ways of the Old Religion, and was well-aware of why she was condemned to die. This was the blood that made the then-Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon particularly enticing as daughter-in-law material to the royals. It did not particularly matter to the royals whether Lady Elizabeth Angela Marguerite was the biological daughter of the family’s French cook, Marguerite Rodiere (as rumored), for her biological father was almost certainly the Earl of Strathmore (just as Diana’s father was also an earl). While not from exclusively royal lines, both the Bowes-Lyons and the Spencers shared the blood of the executed Lady Glamis, and were otherwise aristocrats close enough to royalty for the gate to open.

One of these two brides of royals, Lady Diana, never became queen consort and died young at 36; whether either of her two sons will take the throne remains presumed but uncertain. The other, Lady Elizabeth, who also had only two children, became not only queen consort but also queen mother, and lived an exceptionally long life – an astonishing 101 years. The difference? Diana, a great beauty, could not keep her mouth shut. She shined a harsh spotlight on the closed system of British royalty not just once (which might have been forgivable) but several times (which then made her an absolute threat and sealed her death warrant, as would have been done  in Tudor times).

in Tudor times).  The other, who draped herself in jewels and silks but who was pudgy and dumpy and never a great beauty but a good sport – Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother – stayed indefatigably agreeable and kept her mouth shut her whole life long, all the while greatly enjoying herself.

The other, who draped herself in jewels and silks but who was pudgy and dumpy and never a great beauty but a good sport – Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother – stayed indefatigably agreeable and kept her mouth shut her whole life long, all the while greatly enjoying herself.

Whereas Diana found Prince Charles’s mistress, Camilla Parker-Bowles, insupportable and drew a hard line, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother often openly teased her husband-king about his love affairs, and even called one particularly glamorous actress (a blue-eyed blond dead-ringer for Princess Diana) “Bertie’s girlfriend.”

To the royal court, both were expendable after their childbearing years were done. But the Queen Mother had become the British nation’s jovial, dimply grandma. She was the crone to her queen-daughter’s mother goddess. Princess Diana was the younger goddess, but childbearing was something that Princess Diana was not quite done with yet. She was aging, true, but she had modern medical technology on her side, as well as a willing suitor in Dodi Al Fayed. In fact, at various times in her marriage to Prince Charles, even at its most dire collapse, she’d pestered him about having another baby – something he’d refused to do. And even the British public agreed with Charles – as long as Diana was married to him. But if Diana divorced and married anew, the public recognized that she’d naturally want another child. Childbearing was something Diana was good at. Pregnancy only enhanced her natural radiance. But what of the man who would be by her side? Such a man would be able to influence Diana’s first two children, including the heir apparent to the throne. If Diana married Muslim Dodi and converted to Islam, or at least because a cheerleader for Islam, what kind of effect would that have on Prince William, a likely future king? What of the race-mixing issues? The fact of her fertility alone made Diana infinitely more dangerous to the royals than anyone in their orbit.

But killing the Royal Substitute had become even more difficult than killing the Divine King. Charles I, who publicly proclaimed and fervently believed in his own personal divinity as monarch, was the last king to openly die by execution – his head severed from his body – so that a new king, a soldier who was king in all but the crown that touched his head only as a golden band around his hat, could live and reign. After this, the monarchs who followed the Restoration wrestled with Parliament and, in theory, a kind of royalist democracy that pushed the ritual killing of the monarch and his Divine Substitutes more deeply underground.

However, the British royal family does not have complete control over the sacrificial killing system, and it is obviously important today that no overt acts ever be traced back to them. Murder staged as an unlucky accident became more common in the royals’ world. The “accidents’” choreography requires meticulous planning. This is the work of the Inner Secret Circle. Collateral damage is not unexpected. Sometimes, collateral damage is even welcomed because it distracts the public from focusing on the key victim. Other times, such collateral deaths are simply necessary, as in the case of Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard (whose respective alleged lovers, including Anne’s brother, were also killed). In Princess Diana’s case, the driver of Diana’s car was collateral damage, and Dodi certainly could not be left alive – luckily for the Inner Secret Circle, the driver and Dodi died almost instantly from a severed spine and ruptured aorta. The bodyguard Trevor Rees-Jones’s survival of a wreck that killed two persons immediately and a third somewhat later has always raised questions: Did Trevor, a former professional soldier serving with the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment who served a tour of duty in Northern Ireland, and later went on to work in dangerous “hot spots” like Iraq and East Timor, know of a plan to deliberately cause the car to crash, and so prepared himself to survive? Or was he just “lucky?” Only now, does he know the truth and lives in fear, as some have said? But the Circle’s members are masters at handling the action as well as the publicity and any fallout.

Dead men may tell no tales, but the terrified living are deterred from talking, too.

And wealth also induces silence. Following his recuperation from the crash, Trevor understandably took time to recover, and then went to work “in security” in Iraq, but this time, in a highly-paid position. He then became a security director for Haliburton, working at its Houston offices, and “earned a fortune.” He returned to a newly-bought million-dollar home in the village of Oswestry in Shropshire, England – the town where he grew up from age ten, having been born in Germany to a British army surgeon and nurse. Oswestry is an ancient Iron Age village on the Welsh border, traditionally the birthplace of King Arthur’s Queen Guinevere and her father. Its name derives from “Oswald’s tree,” and came about after the Battle of Maserfield on August 5, 641 or 642, when the pagan king, Penda of Mercia, defeated the newly-Christianized King Oswald of Northumbria. King Oswald’s very name tells a story that was ancient even at the time of his own birth in 604 A.D. “Os” meant “god,” and “Wald” derived from “wealed,” meaning “rule.” The Old High German name was “Answald,” and in ancient Norse, “Asvaldr.” Christianity later turned Oswald and the “Os” line of divine kings into saints from pagan gods. The family’s ancestral crest is, variously, a six-or-eight-pointed star, or comet. This comet crest was also the personal sign of Julius Caesar, the Roman emperor-turned-god. Caesar’s Comet, also known as the Great Comet of 44 B.C., was seen for seven days in July 44 B.C. after Julius Caesar’s assassination, and was considered proof that, through a murderous death, Julius Caesar had become a god. Augustus, Caesar’s nephew and adopted son who succeeded him, had a comet star medallion affixed to the forehead of Julius Caesar’s statue which stood inside the temple dedicated to him, reflecting the words of the poet Ovid, who wrote, “To make that soul a star that burns forever.” This deification was encouraged and made official by Augustus. However, Augustus was merely the heir to much older traditions of linking stars (and especially blazing comets) with gods. In a post-battle pagan rite, Penda cut off Oswald’s arms, hands and head, apparently while Oswald was still alive; his wounding in the battle was unclear. Oswald’s head and appendages were put on poles while the rest of his body still writhed on the ground.

A raven then swooped down, seized one of Oswald’s arms, and flew with it to an ash tree, where the raven dropped the arm, and blood from the arm fell upon the tree and flowed to the ground. A freshwater spring, called Oswald’s Spring, suddenly burst forth, and many other miracles were attributed to Oswald’s tree and the waters flowing near it. In the Middle Ages, even hundreds of years after Oswald met his death, the town named for him and his ritual death thrived, and his cult spread across Europe. Comparisons were made to Jesus being crucified on a cross – a “tree” – and Oswald’s arm being put on a tree. Oswald’s name itself – derived from the pagan god, “Os,” or “Odin,” was deliberately minimized by the Church – as was Oswald’s entire bloodline of “Os” kings. But not even the Church could escape the belief that Oswald had died in the manner of a pagan king being ritually sacrificed. A statue of the raven – a symbol for Odin – grasping Oswald’s severed arm marks the site of Oswald’s Spring (now a well) even today. Oswald’s decapitated head eventually found its way to Durham Cathedral, where it is said to rest with the remains of St. Cuthbert – who is sometimes depicted in art as gently cradling Oswald’s severed head in his arms. Competing European shrines dedicated to Oswald similarly claim to have various of his body parts, which in fact may be true, since accounts say that Oswald’s kin dug his body up from Maserfield, and delivered it to holy places. Hildesheim Cathedral in Germany claims to keep Oswald’s severed head in an elegant reliquary, where it regularly delights pilgrims and is said to bring forth miracles.

Oswestry became famous and remained famous because it is a place that marks where the king died so that the new king could live, and the kingdom prosper. Even the grass there where Oswald had walked and died and where his blood was spilled was held to be special, if not sacred. And this was typical not just of Oswald, but of kings generally, who were traditionally slain in “the ritual king-laying of paganism” practice. Christianity made these ritually-murdered kings into popular saints, but paganism turned them into gods. The very name-prefix, “Os,” was an identifier meaning “Divine.”

Some scholars of royalty and religion (now deceased) would have certainly recognized Princess Diana’s murder as just the most recent Divine Substitute sacrifice, but like all its precedents, Diana’s murder is encoded in a system of powerful magical and religious primeval symbols and archetypes that exist largely in our subconscious, and are seldom recognized outside it. However, something about Princess Diana’s life – her obvious goddess-like attributes, her avatar nature, her gamine boyishness tied to real glamour – opened wide a crack in the world’s subconscious that now gives people the correct impression that her shocking death in Paris was not accidental, and that an ancient story of mythological proportions was being re-enacted in a seemingly incongruously modern time and setting.

And yet, incongruity is merely a perception; the story is an eternal one.

Royal Vengeance makes comparisons to other assassinations and attempted assassinations in both ancient, classical and modern history, using original sources wherever possible. The United States has no kings, but it did have Huey Long, a populist Louisiana senator who declared “Every man a king!” and called himself “the Kingfish.” America also had a figurative king and queen in President John Fitzgerald Kennedy and his glamorous wife, Jacqueline, who called their White House years “Camelot” – after the idealized reign of King Arthur. However, despite claims that Jackie plagiarized the Camelot metaphor from JFK’s favorite Broadway musical, one cannot help but note the eerie similar parallel between the Camelot show that is actually a tragedy and mystic tale of a murdered king, and another popular novel and film that was a JFK favorite, The Manchurian Candidate, that foretold JFK’s assassination by a former soldier who was brainwashed to shoot the president by foreign communists – years before Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested as JFK’s assassin. Just like the monarchs of Britain and their Sacrificial Victims, both Long and Kennedy were violently assassinated and their blood was made to fall upon the ground. And for both Huey Long and John Kennedy, their assassins (or those believed to be their assassins) were also deliberately murdered, with their blood made to fall upon the ground. Kennedy, scion of an ancient Irish family descended from royalty, was allegedly assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald, whose surname also invokes ancient divinity. Oswald was then himself murdered by Jack Ruby. So, who was the real sacrifice?

A similar analogy is possible for Huey P. Long, murdered by Carl Austin Weiss—“Austin” deriving from the Irish name Oistin, meaning “august” (as in the Roman emperor), “dignified,” and “holy – a divine personage.

So now, let us return to the history you swallowed before.

In 1542, a young, beautiful and vivacious queen who was very much the celebrity of her day – Catherine Howard – was suddenly found guilty of taking lovers while married to Henry VIII. Before she herself was executed for treason against the king, her lovers (on trial for their lives) were interrogated by her uncle, Thomas Howard, third Duke of Norfolk – one of the most powerful peers in the realm (and also the older brother of Edmund Howard, Catherine’s deceased father). The French Ambassador, Charles de Marillac, observed the proceedings and expressed his horror in reports to his sovereign, Francis I. The Duke, Marillac reported, laughed uproariously throughout the trial of his niece’s lovers “as if he had cause to rejoice,” even though the Duke must have certainly known he was sending all three of these handsome and fertile young people to their deaths. The Duke’s son, Henry Howard, also attended the trial and supported his guffawing father. Catherine’s own brothers were observed parading around town on horseback while their sister’s life slipped away. Even young Catherine herself, a teenager, was engaged in what can only be described as giddiness. The Spanish ambassador, Chapuys, wrote to the Emperor Charles V on January 29, 1542, of the almost overly-royal behavior of Henry’s doomed young queen: “It is to be feared that the Queen will soon be sent to the Tower, who is still at Syon [House] making good cheer, fatter and more beautiful than ever, careful in her attire, and more imperious and difficult to serve than when she was with the King, although she expects death, and only asks for a secret execution.” And when she realized there was no escaping her fate, little Queen Catherine Howard did not spend her whole last night on earth praying or bewailing her cruel fate, but dutifully practiced for her own beheading, asking that the actual chopping block be delivered to her Tower rooms so that she could figure out how to properly place her head there the next morning.

Shortly after 7 a.m., following a night of careful practice, Queen Catherine Howard was decapitated, encircled by all the King’s councilors except for the Duke of Suffolk (who pleaded illness) and her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, who’d absented himself but sent instead his young, handsome eldest son, Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. Shortly after her execution, The Spanish ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, wrote the Emperor Charles V that Henry VIII “has been in better spirits and during the last three days before Lent there has been much feasting.”

“Much feasting?”

Henry was said to have invited twenty-six ladies to join him – which Margaret Murray identifies as “two covens of thirteen.”

What in God’s name was going on?

And in which god’s name?

Marillac, who’d spent three years as the French Ambassador in Constantinople before coming to London, blamed it on England’s peculiar ways: “Such is the custom of this land,” he cryptically wrote the French king. Fenelon, the French Ambassador Marillac replaced, had earlier said of the Howard family: “They are subject to be beheaded and cannot avoid it, because they come of a race naturally given that way.”

Do you see something new yet? Anything different?

Centuries later, the beauteous Lady Diana Spencer’s maternal grandmother, herself a lady-in-waiting to the Queen’s mother, tried to warn her granddaughter away from marrying Prince Charles and entering the royals’ fold. In an oft-quoted advise that was the purest form of understatement, Lady Fermoy told Diana: “I don’t think marrying into the royal family will suit you. Their sense of humor and their lifestyle are very different.”

Marriage within the royal fold was not only “different” but incalculably dangerous.

The history you swallowed all your life says that this is normal politics – that killing queens, nobles and aristocrats is all perfectly normal – just power politics played large and showy; that there are no gods and no goddesses, and no need for kings to routinely die or for nobles to die in their stead, or to have any divine human blood spilled upon the land. The history you swallowed says that Princess Diana died in a run-of-the-mill traffic accident at the hands of a drunk driver in a tunnel that ran underneath the Seine in Paris – something so mundane that could happen to anyone. Every royal death and every death close to the royals is explained away as “normal” and understandable in the history you swallowed. Religion, we’re told, doesn’t enter into it. And paganism isn’t even mentioned.

And yet, scratch the surface, and one finds paganism everywhere in Britain – even in holiest Christian places. It was there thousands of years ago, long before Christianity ever came. Even today, paganism persists. It thrives in the divine monarchs. It bursts throughout country churches and great cathedrals alike in the displays of nature carved in wood, vines running in and out of humans’ eyes, ears and mouths, in jarring stained glass telling the most mysterious of stories, in mischievous imps and even toothy, eye-popping stone snakes encircling columns that were looted from far older temples; even the locks atop old baptismal fonts stem from a papal order to prevent witches from stealing the churches’ holy water to craft their powerful spells. Paganism was born with Britain, it survived the great purges, and it will be there tomorrow because this is the system not just of English kings, but of the English people. It’s a system they intuitively respond to and intuitively obey. They will be the first to cheer when the old monarch dies, and a new monarch lives. It is on their backs that an old dead monarch is brought to burial, and on their shoulders that a new, younger monarch is carried into divine kingship. Along the way, blood will be shed.

Let’s take a deeper look.