Royal Vengeance: The Assassination of Princess Diana and the Ancient Royal Cult of Human Sacrifice

Royal Vengeance: The Assassination of Princess Diana and the Ancient Royal Cult of Human Sacrifice

Copyright ©2020/2021 Sarah Whalen. All Rights Reserved

Published by:

Trine Day LLC

PO Box 577

Walterville, OR 97489

1-800-556-2012

trineday@icloud.com

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021941425

Epub (ISBN-13) 978-1-63424-149-6

Print (ISBN-13) 978-1-63424-148-9

1. Diana — Princess of Wales — 1961-1997 — Death and burial. 2. Monarchy — England — History — To 2000. 3. Great Britain — Kings and rulers — Religious aspects. 4. Paganism — England — History — To 2000. 5. Occultism. 6. Conspiracy. I. Title

Portions of this book have been serialized on our website and Facebook.

First Edition

Distribution to the Trade by:

Independent Publishers Group (IPG)

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

312.337.0747

www.ipgbook.com

Publisher’s Foreword

I come no more to make you laugh: things now,

That bear a weighty and a serious brow,

Sad, high, and working, full of state and woe,

Such noble scenes as draw the eye to flow,

We now present. Those that can pity, here

May, if they think it well, let fall a tear;

The subject will deserve it. Such as give

Their money out of hope they may believe,

May here find truth too.

– William Shakespeare, The Life of King Henry the Eighth

Now learn the parable from the fig tree: when its branch has already become tender and puts forth its leaves, you know that summer is near; so, you too, when you see all these things, recognize that He is near, right at the door. Truly I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place.

– Matthew 24:32-34

Time will tell, it is said. But what is it that time tells? The truth? Does everything come out all right in the end? What is the power of time? Will we as a people ever know the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth – so help us God? Does the passing of time get us closer to the truth? Do we know the truth of our past? Does it matter?

Sarah Whalen’s Royal Vengeance: The Assassination of Princess Diana and the Ancient Royal Cult of Human Sacrifice is a deep, deep dive into our hoary past. Sarah presents persons and events that we are familiar with, plus she weaves a backstory that has eluded many. Building upon the works of obscure authors and years of research, Royal Vengeance takes readers on a wild ride down the rabbit holes of history.

Onward to the Utmost of Futures!

Peace,

RA “Kris” Millegan

Publisher

TrineDay

June 21, 2021

By this, the boy that by her side lay kill’d

Was melted like a vapour from her sight,

And in his blood that on the ground lay spill’d,

A purple flower sprung up, chequer’d with white,

Resembling well his pale cheeks and the blood

Which in round drops upon their whiteness stood.

– William Shakespeare, Venus and Adonis

PREFACE: Where the Road May Lead…

All roads of western civilization lead to Rome, goes the adage, and yet history is oddly quiet, even mysterious, about from where these roads originated, the detours taken, and whether Rome was always the final destination.

In England, the roads leading famously to Rome came early, with Julius Caesar’s conquest of Gaul. These roads did not survive local uprisings and soon fell victim to Caesarian Rome’s own over-extension of itself; but Rome did leave behind an indelible influence. But one road leading to Rome was, centuries later, famously severed by Henry VIII, who then built quite a different highway for himself and the English nation. But in fact, Henry’s highway was erected atop an already well-worn by-path of peoples and cultures that crisscrossed the nation he strove to reign over – and these peoples and cultures were far older than Rome’s. Some of these pathways were hacked out from the earliest peoples who came from the most ancient human enclaves. They settled at the fringes of ancient Britain, chasing wild deer and game, and then electing to remain. They worshiped gods and goddesses of fertility, worshiped the sun and the moon and the stars, believed deeply in the gods of rivers and the goddesses and nymphs of sacred, fresh-water springs, and bowed long and low to the cosmic forces which held their world together. These cosmic forces were universal and, at the same time, particular to the tribe.

And there were many different tribes, each of which took a territory and then fought to the death for that land and for the people inhabiting it.

But the tribes, both “native Britons” and invaders, of what later came to be called “England” had in common one special thing – they were led by a man whose body – whose self – was considered sacred, and they called him their “king;” and the king himself was the center of the cult of his own worship as a living god.

Call him the Divine Man who becomes the Divine King.

The Divine King and its concepts was present even amongst the cave-dwellers of Britain’s earliest human inhabitants. This belief – codified into a distinct practice – stayed and thrived through countless incursions and invasions, including those of the later Saxons, Normans and Plantagenets. The practice of the Divine King (and Queen) reached its apex during the reign of the Tudors – particularly under Henry VIII. The most fixed, mystical and occult of its tenets was that the old king must die so that the new king could live, and the people be saved thereby, and the world, enmeshed by cosmic forces beyond human control, would not only continue but do so prosperously.

The key was in spilling the Divine King’s blood upon the ground, where it would fertilize and re-nurture the world.

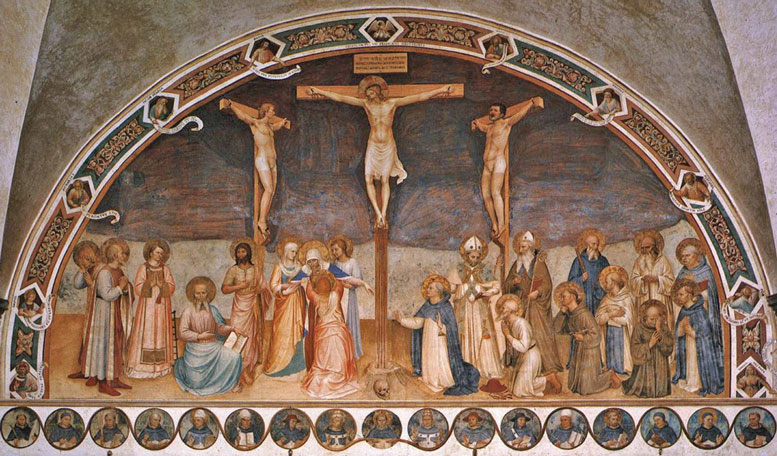

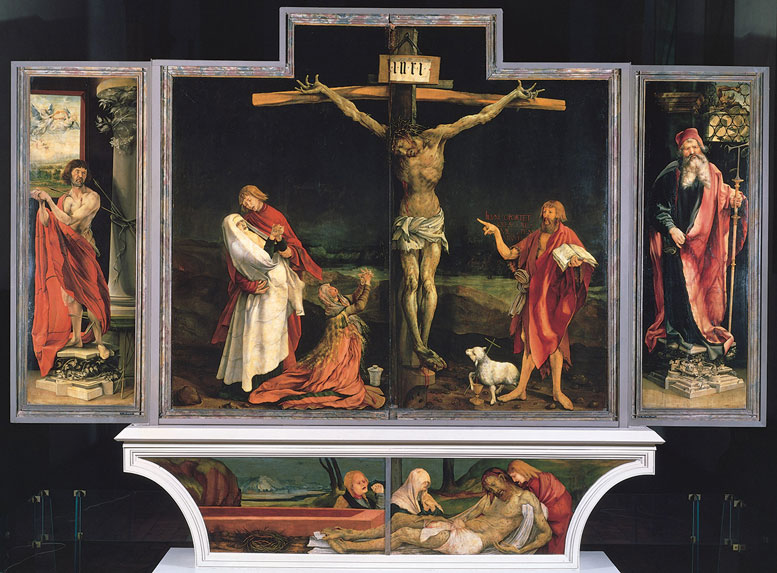

It is certainly no accident that, in the most famous of all divine living sacrifices – that of the “King of Kings,” religious art consistently shows the blood of Christ crucified as dripping down from his bodily wounds suffered upon the cross until it falls upon the ground below. Sometimes, as in Hendrick ter Brugghen’s “Christ on the Cross Between the Virgin and St. John the Evangelist” (1625), upon the ground are seen a human skull and bones – said to be that of the first man – Adam, whose original sin of the Garden of Eden is now redeemed by being touched by a mere trickle of the Savior’s holy blood. St. John the Evangelist is portrayed looking at Christ’s blood not in horror, but in deep and respectful contemplation – a process which led to St. John writing the Book of Revelations in which the bloody robes of the martyrs are said to have been made white when “washed in the blood of the lamb.” Fra Angelico’s “Crucifixion” (1420-23) similarly portrays the tableaux with Jesus’s dripping blood as the focal point. Innumerable Greek icons and Byzantine art typically portray the crucified Jesus’s blood falling on the ground – often in gushing flows. But one in particular shows the Virgin Mary not collapsing at the sight of her son’s blood dribbling upon the earth, but instead watching it, with measured awareness, strike the skull and bones of Adam. Matthias Grünewald’s “Crucifixion” (1512–1516) shows blood dripping down Jesus’s legs, twisted in pre-death spasms of agony, where it falls in a rivulet directly upon the ground; alongside, a white lamb – a substitute sacrificial figure – holds a cross and a cup into which its own gushing blood flows. It is a subsequent innovation that artists like Van Dyck, Rubens, El Greco and Simon Vouet show Jesus’s blood not falling on the ground, but being vigorously wiped clean off from the cross itself by Mary Magdalene and angels – a reflection on the growing practice of dipping one’s handkerchief or other cloth in the blood of dead royals or their substitutes.

These were no mere grisly souvenirs; the blood of slain kings and their Substitutes was considered life-giving, health-restoring and even magical. In more occult works, like Luca Signorelli’s “The Crucifixion with Mary Magdalenee” (1500), the crucified Jesus is beheld by Mary Magdalene, and his blood and her flowing life-force cause tiny flowers to bloom around them in a broken circle of budding fertility just beginning to fill itself into wholeness; even Adam’s grotesque skull has a snake-like vine or root (or is it a snake?) curling around its jaw. More enigmatic is an ivory Crucifixion plaque from seventh-century Reims that shows a coiled snake beneath Jesus’s feet, licking up the blood.

English kingship was, and is, a cult of fertility. The king was a living god who linked the land and the people to the even greater gods. Even the Christian God was understood as a heavenly monarch. Middle pagan genealogies traced monarchs’ descent to Odin, or Wodin; after Christianization, genealogies traced monarchs’ decent from Noah or, more recently, cousins of the Virgin Mary (and, even later, from the Virgin Mary herself). One thing striking about the many tribes of early England is that, in eventually receiving the Christian Bible, some recognized a kinship of interest with the twelve tribes of Israel; as a result, social mores of the time often reflect the more warlike qualities of the tribes of Israel rather than the more pacific, deliberate and organized qualities that evolved from the Roman state, which not only briefly and previously conquered England, but also, once Christianized, remained the organizing influence behind the Roman Church. But it is the same Roman Church which found only an unsteady foothold in England before being expelled and dispossessed almost entirely during the Reformation and beyond – an exile so deep that Roman Catholics could barely be suffered to live.

Roman Catholic families like the Howards were allowed to remain steadfast in their religion and possessed of at least some of their great wealth because, for centuries, they cooperatively served a unique purpose for the English king – one that Henry VIII made use of the most. The Howards showed a willingness to dutifully sacrifice themselves so that the king could live.

While cycles of kingship sacrifice were based on the monarch’s “luck” – the obvious favor of the gods as shown in good or bad weather, plague, drops or surges in fertility, or comets or even the seasonal appearance of stars – sometimes, but not always, a Divine King (lucky or unlucky) might escape his necessary death by providing a substitute sacrificial victim – the Substitute Victim. The Substitute Victim was a person who, like the king himself, was of royal blood or similar royal or at least aristocratic status. Later, kings also used archbishops and “Princes of the Church” as Substitute Victims. And why not? Kingship had become far more comfortable than in Britain’s earliest past, and kings wanted to live to enjoy it. As English society modernized and the pagan forces that shaped it were being increasingly driven underground, the use of a Substitute Victim in place of the actual Divine King (or Queen, in later Tudor times), became more common. A very idiosyncratic legal system made it exceptionally easy to disguise these divine sacrifices as the judicial killing of people found to be criminals (usually for some variety of treasonous behavior – which is a defining factor even abstractly because it implies usurpation, or acting like a king) became increasingly common. As laws became more refined and popular notions of democracy took root (in part, beginning with the 1524 Peasants’ Revolt), enterprising royals and the courtiers who served them became more inventive in how to procure the deaths of Substitutes – many of whom were now less than willing to die so that the king could live.

Princess Diana infamously recalled that, as she walked down the aisle of St. Paul’s Cathedral at her 1981 wedding to Prince Charles, she felt like the sacrificial “lamb to the slaughter.” But as her spirited life and her secret literary efforts show, Diana was far from wanting to die as a Substitute Victim. It was a fate she truly believed she’d escaped from by her divorce – but when faced with death in the hellhole of the Alma Tunnel and, hours later, in the ambulance, she resisted and raged against it, right up until the end.

Princess Diana fought hard for every last minute of her life, against impossible odds and evil people – men and women – who sought to murder her. In this last fight, she was transformed from Virgin to Princess to Goddess to a Warrior, the legendary Amazons and even her own ancient ancestors would have been proud to call one of their own.

And yet, it is exactly the many other historical examples opposite Diana’s fight to the finish that are so very striking to our modern sensibilities – that so many noblemen and women went so readily, willingly and even eagerly to their own deaths, accused of the most heinous crimes for which there was rarely any evidence at all.

Sometimes, the familial power, wealth and prestige that came (sooner or later) once a family member had died as a Substitute Victim was so enormous and tempting (at least, to the survivors) that certain families, such as the Howards and Boleyns, became renowned for their willingness to serve as Divine Substitutes. But even with the Howards and Boleyns, pure religiosity and a “joy” that was both genuine and determined seem to be the main motivators behind these willing walks to the scaffold – once the die had been truly cast and despair set aside.

And, from most ancient times, cutting off the head was the oldest, and most glorious, kind of death.

William A. Chaney, in his seminal work, The Cult of Kingship in Anglo-Saxon England, calls this idea an “extreme theory.” He particularly singles out the work of Margaret Alice Murray, an anthropologist, whose researches on witchcraft, paganism and royalty stirred controversy and evoked ridicule from scholars, admiration from readers, and fear from the descendants and heirs of the personages she studied so dexterously and, some said, creatively.

After much study and consideration, I not only acknowledge the truth and evidence of Murray’s “extreme theory,” but take her theory further, into our current day. Murray claimed that all practice of Divine Kingship in England ended with the execution of Charles I (or even before) – but I doubt this. My research shows deaths associated with royalty and political figures, elected royals, nobles, and aristocrats and their retainers occurring at least once every royal generation that are unusual and not easily explained. I also discuss a few modern attempted assassinations of monarchs that appear to be almost ritual pantomimes of earlier, more fatal practices. To survive – covertly – into modernity, the old practice of Divine Kingship and the deeply religious beliefs that were wedded to it underwent a deep transformation, mixed in with a Christianity that was itself significantly transformed by the process.

And that brings us to the seminal question: Was Princess Diana murdered by the British Royal Family? My answer is again yes, and the reasons for this were complex. Was Diana a Divine Substitute? My answer is yes. Her 1997 death in Paris is one reason British aristocrats have so firmly slammed shut many doors to marriage with a modern member of the Royal Family. For the first time ever in its history, all close members of the Royal Family are now married to (or were married to, in the case of Prince Andrew) commoners. Even wealthy aristocrats have fewer surviving children than in the past (lower birthrates being what they are) and they are now loathe to offer up their precious offspring to a life of wealth, privilege and mystical uncertainty that may end in that child’s violent death so that the king may live. No modern English aristocratic families seem as willing as the Howards and Boleyns were to achieve enormous social and financial elevation at such a wrenchingly high price – at last, after following the death of the Spencer family’s most beautiful and youngest daughter. The Kate Middleton and Meghan Markel arrivistes (along with their colorful extended families), whose brazen, fierce ambition would have been frozen out by notoriously controlling courtiers, the infamous “Men in Grey,” even half a century ago, are now spouses of high-ranking royals and in-laws of a reigning queen, two future kings.

However, royal families “move with the times” while still keeping their older customs alive. But bloodlines (or lack of them) aside, Kate Middleton’s and Meghan Markel’s royal marriages have ennobled them, but have also made them expendable players in the royal cult of English kingship.

In examining Princess Diana’s death and the forces behind it, I also examine the lives of others who may have unwittingly served as similar Divine Victims. These include Diana’s lover and bodyguard, Barry Mannakee (allegedly killed in a freak automobile accident); Alethea Savile, fiancé of Diana’s lover and “Squidgeygate” confidante, James Gilbey (who allegedly committed suicide by drug overdose, found dead with a fatal head wound); Alisa Dmitrijeva, a 17-year-old Latvian immigrant girl whose murdered dead body was found by a dog walker on New Year’s morning, 2012, at the Queen’s Sandringham estate near the Royal Stud (where the Queen herself oversees the breeding and training of her racehorses); and Hugh Lindsay, a former courtier married to another courtier, who was killed on a royal ski trip by an avalanche said to have been triggered by the Prince of Wales and his skiing party. Whether intentional or accidental, there is a clear mark of death on those who travel closely with the king (or king-to-be) in England – and there always has been. Shortly before her own unexpected death at age 45, Tara Palmer-Tomkinson, the sexy, beautiful and engaging London “It” girl whose parents are Prince Charles’s best friends (whose parents were skiing with Charles when Hugh Lindsay died, and whose mother, Patty, was seriously injured in the avalanche but survived), made flirty and even lascivious and pedophilic-erotic suggestions that she’d not only had sex with the future king (gleefully asking a talk show host if he wanted to know “how big” Prince Charles’s penis was), but had “kissed him every day since she was four years old.” She was seen quite clearly “sharing” a kiss with Prince Charles on the slopes in 1995 – while he was deep in the throes of negotiating his divorce from Princess Diana. Charles had reportedly banned Tara from his après-ski soirees after she’d flashed her naked breasts at a young and impressionable Prince Harry during a Klosters house party. Later, she was seen with an older man, a “new boyfriend” who reportedly would not let her go around to her old neighborhood pub anymore and chat up the bartender, as she regularly did. A few months later, she was found dead in her chic London apartment by her cleaning lady. Was it from an untreated ulcer? A brain tumor? Had Tara’s old demon drug-habit finally killed her? Did she kill herself with drugs in the throes of some despair? Was the grey-haired “older man” Tara’s drug dealer or someone even more sinister?

Or was it all something more than that?

Who will next die so that the king will live?

And do not think that all these things only happen in England. When the English came to America, the cult of kingship, murder and royal blood came with them; nor did the cult depart from the thirteen colonies after the American Revolution. Murders of American “royalty” like that of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy (“Camelot’s King”) and Louisiana Senator Huey P. Long (the “Kingfish” whose campaign slogan was “Every Man a King”) and, in the case of Presidents Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford, attempted murders, are all part of the persistent and deeply royal cult of blood sacrifice. Much further speculation about such persons who appear as gods and goddesses in life today includes Hollywood “royalty,” at least four other presidents, senators, rock stars, and heroes.

Queen Elizabeth II once famously said, “I must be seen to be believed.”

This nonagenarian, white-haired, dripped-in-diamonds monarch sits upon a throne washed in centuries of human blood. The blood running through her veins is fat with the genes of ancestors whose kingships were established and extended by people who died so that they could live. Supporting the monarch and her descendants in their hunger is a super-select Inner Secret Circle that has operated from time immemorial, and continues to move in the shadows today to safeguard the royals from their own deadly traditions – and that means that others near to them are always in danger.

Like Princess Diana and Dodi, sometimes they die in the most mysterious ways; and yet, with time, a pattern can be seen.

Believe it.

This is what my book is about.