Allegations regarding “Butch” Merritt, Watergate, Intelligence Agencies and “Crimson Rose,” Vol. X

Nixon on Drugs – Part Three

Written (and first posted) by Kris Millegan, March 25, 2011

What I meant is, you could get a million dollars. And you could get it in cash. I know where it could be gotten. — Richard M. Nixon, March 21, 1973, Oval Office

Where does one get $1,000,000? In cash? And in secret?

Again, the evidence is in, Nixon was very comfortable with blackmail. It was his modus operandi, his mileu.

Watergate got rid of a blackmailer, but not before the blackmailed got their money’s worth. Nixon had things to do, before he could be “let go” … leaving the Presidency in disgrace. “They” knew they could always embroil “Tricky Dicky,” with a scandal. The Townhouse affair wasn’t quite sexy enough. But along came a very controlled scandal, Watergate, and Nixon was in the bag.

Again, some detail (notice the players and the assassination squads) from the 1980 out-of-print book, The Great Heroin Coup – Drugs, Intelligence, & International Fascism by Henrik Kruger:

SIXTEEN

THE FRIENDS OF RICHARD NIXON

Richard Nixon’s connections to the Syndicate and its stooges are a matter of record. The only question is when they began. Some say it was 1946, when Nixon ran for Congress in California and Murray Chotiner, a top Syndicate defense attorney, ran his campaign with support from the gangster Mickey Cohen.[1]

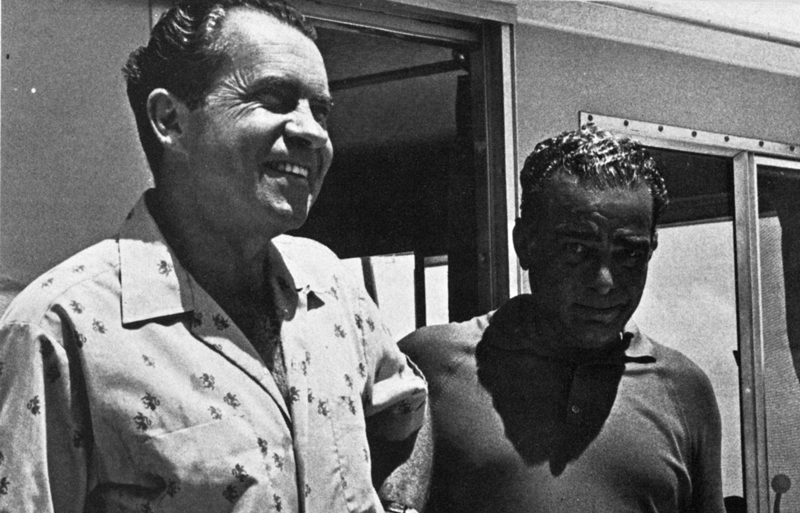

Others place the Nixon‑underworld wedding as early as 1943, when Nixon was working in the Office of Price Administration, at a desk responsible for controlling the market in rubber goods. There he allegedly met his future pals George “The Senator from Cuba” Smathers and the Cuban‑American Bebe Rebozo who later struck it rich in real estate. The two were then small time: Smathers a lawyer for a Syndicate front smuggling auto tires from Cuba, Rebozo the owner of a gas station that sold the tires.[2]

The Florida clique was a happy family. Nixon liked to take fishing jaunts with the likes of Rebozo, Meyer Lansky’s associate Tatum “Chubby” Wofford,[3] and Richard Danner, who would later manage the Sands casino in Las Vegas for Howard Hughes.[4] He also got to know people even closer to the Syndicate, who had extensive interests in Cuba. In 1952, one short month after the dictator Batista’s comeback, Nixon and Danner joined throngs of tourists who unloaded their savings at one of the Syndicate’s Cuban casinos.[5] Nixon would return frequently. He, Rebozo, and Smathers allegedly invested in the island during the fifties,[6] and in 1955, as vice president of the United States, Nixon would pin an award on Batista, with whom he was photographed in the dictator’s palace.

Nixon also helped plan the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1959. Chairing the 54/12 Group, a National Security Council subcommittee in charge of covert actions, the vice president pushed for the plan’s approval before his 1960 presidential race against John F. Kennedy.[7] According to Howard Hunt, Nixon was the invasion’s “secret action officer” in the White House.[8] President Eisenhower, who would later plead ignorance of the plan’s extent, assumed it was limited to support for anti‑Castro guerillas in the mountains.[9] When JFK took over the oval office, he was presented with a fait accompli.

If Eisenhower was really left out in the cold on the plan’s magnitude, then William Pawley must have been among Nixon’s co‑conspirators. As mentioned earlier, Pawley talked Eisenhower into arming the anti‑Communist Cubans.[10] Pawley was and would remain one of Nixon’s most ardent supporters.[11]

When the invasion proved a bust, Nixon’s voice was among the loudest accusing Kennedy of undermining it by refusing reinforcements. In the years that followed he continued to cultivate support among the Cuban exiles and other right wing constituencies. Cubans for Nixon and Asians for Nixon touted him as a man who would not forsake the cause of anticommunism. The Nixon of near‑hysterical anticommunism would win additional allies in the Syndicate and in powerful business circles tied in with the military and espionage.[sic]

Fortunately for Nixon, forces behind the above lobbies were also influential in organized labor, especially the Teamsters Union. Teamster boss Jimmy Hoffa became a pawn of the Lansky syndicate, which borrowed millions from the union’s pension fund. However, Hoffa’s obsequiousness towards the Mob was dampened by Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s aggressive investigation of Teamster policies. In 1967, prior to Nixon’s decisive electoral campaign, Hoffa landed in jail with a thirteen‑year sentence for misuse of union funds. The new Teamster strongmen, Frank Fitzsimmons and Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano, were friends of Nixon and in the hands of the Syndicate.[12] When Nixon pardoned Hoffa just prior to Christmas 1971, Hoffa had to promise to stay out of organized labor.

In the sixties Nixon grew even closer to his friends in Miami, who by then had made millions in land speculation. Dade County north of Miami became known as “Lanskyville,” as a string of seemingly legitimate real estate firms handled the Lansky Mob’s enormous holdings. Among the more prominent firms were:[13]

1) The Cape Florida Development Co., run by Donald Berg and Nixon’s pal Rebozo. The two worked closely with Al Polizzi, the former head of the Syndicate’s Mayfield Road Gang in Cleveland, then in charge of the Syndicate’s Florida contractors. An investigation into the placement of stolen securities at Rebozo’s bank was nipped in the bud.

2) The Mary Carter Paint Co., which in 1967 became Resorts International, that now runs the world’s most profitable casino in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and was purportedly the brainchild of Mr. Lansky. Resorts’ Paradise Island casino in the Bahamas was managed by Ed Cellini, a longtime Lansky casino operator.

3) The General Development Corp., run by two Lansky strawmen, Wallace Groves and Lou Chesler. Its board of directors included Lansky broker Max Orovitz and the gangster Trigger Mike Coppola. Groves bought up half of Grand Bahama Island for the Syndicate and contracted with Nixon’s law client, National Bulk Carriers, to construct a harbor there.

4) The Major Realty Co., whose controlling shareholders were Senator Smathers and Lansky’s men Orovitz and Ben Siegelbaum.

Through his friends, Nixon acquired land on Key Biscayne and Fisher’s Island, off the Florida coast. In return he readily made himself available for personal appearances. When Mary Carter in 1967 opened the Nassau Bay Club casino on Grand Bahama Island, Nixon was the guest of honor. One year later he was there when Resorts International opened its casino on Paradise Island.

Nixon also expressed his friendship in other ways. Hoffa was not the only one who did not have to pay his full debt to society. Neither did Leonard Bursten, Carl Kovens, or Morris Shenker, all Syndicate associates, the last two solid Nixon campaign supporters.[14] Robert Morgenthau, the federal attorney for the southern district of New York, became interested in some of Nixon’s friends in 1968. He proved Max Orovitz guilty of willful violation of stock registration laws, and was investigating Syndicate money transfers to Switzerland. The latter threatened to lead to an indictment of Nixon’s friend John M. King of Investor’s Overseas Service (IOS).[15] Morgenthau, however, was removed from office.

Glancing at major contributors to Nixon’s 1968 and 1972 campaign chests, one finds the names of Miami straw men Lou Chesler and Richard Pistell, Resorts’ president James Crosby and John M. King, the Texas billionaire Howard Hughes, master swindler Robert Vesco, and the California millionaire C. Arnholdt Smith, a close associate of the gangster John Alessio and later convicted of misuse of bank funds.

The list of Nixon’s major personal and political supporters starts with Rebozo, Smathers, Dewey, Hoffa, and Frank Fitzsimmons, all with their Syndicate associations; and goes on to include William Pawley and the China Lobby’s Madame Anna Chan Chennault.

Nearly all of Nixon’s major supporters in Florida were involved in one way or another in the Bay of Pigs operation. The same can be said of the top Syndicate figures, four of whom escorted the invasion force in a yacht for part of the voyage, while Trafficante’s lieutenants in Miami and the Dominican Republic stood ready to seize the casinos.

Moreover, one cannot overlook Nixon’s particular connection to IOS‑multimillionaire Vesco, who until recently was in exile in Costa Rica, where he allegedly financed the smuggling of narcotics.[16] Vesco provided covert financial aid to Nixon’s reelection campaign, and was closely associated with Nixon’s brother Edward and nephew Donald, Jr. Richard Nixon himself is alleged to have met secretly with Vesco in Salzburg, Austria.[17] The White House, finally, came to Vesco’s aid in a case brought against him by the Securities and Exchange Commission,[18] just as an investigation of his narcotics activities was similarly choked off.[19]

pps. 153-157

–[Notes]–

1. H. Kohn: “Strange Bedfellows,” Rolling Stone, 20 May 1976.

2. C. Oglesby: “Presidential Assassinations and the Closing of the Frontier,” in Government by Gunplay, S. Blumenthal and H. Yazijian, eds. (New American Library, 1976).

3. The 1950 Kefauver investigation discovered that one of Lansky’s largest back room casinos in Miami was set up in the Wofford Hotel run by Tatum “Chubby” Wofford.

4. Howard Hughes helped Nixon out as early as 1956 with a secret $100,000 donation, as well as a $205,000 loan to his brother Donald.

5. J. Gerth: “Richard Nixon and Organized Crime,” in Government by Gunplay, op. cit.

6. Kohn, op. cit.

7. H.G. Klein in the San Diego Union, 25 March 1962.

8. Kohn, op. cit.

9. Oglesby, op. cit.

10. M. Acoca and R.K. Brown: “The Bayo‑Pawley Affair,” Soldier of Fortune, Vol. 1, No. 2,1976.

11. J. Hougan: Spooks (William Morrow, 1978).

12. Time, 18 August 1975. Six months after an 88‑count indictment, Frank Fitzsimmons’ son Richard, a Teamsters organizer, was recently sentenced to thirty months and a $10,000 fine for accepting bribes from trucking company officials (Boston Globe, 16 February 1980).

13. Information on the four firms is from the October 1972 NACLA Report.

14. Bursten, a friend of Hoffa’s who was at one time a director of the Miami National Bank, saw his fifteen‑year sentence, in connection with the bankruptcy of a Beverly Hills housing development that had received a $12 million Teamster pension fund loan, reduced to probation after the intervention of Murray Chotiner. Kovens, another leading Florida Teamster official, was convicted in the same pension fraud case as Hoffa, but released from federal prison with the help of Senator Smathers. and then went on to collect $50,000 for Nixon’s 1972 reelection campaign. Shenker, whom Life magazine in 1971 called the “foremost mob attorney,” saw the Justice Department’s multi‑year investigation of his tax violations turned down by Nixon’s Attorney General Richard Kleindienst on the basis of “insufficient evidence,” after which the files on Shenker at the offices of the U.S. Attorney at St. Louis disappeared; see Gerth, op. cit.

15. NACLA Report, op. cit.

16. Hougan, op. cit.

17. Ibid.

18. Time, 6 May 1974.

19. L.H. Whittemore: Peroff (Ballantine, 1975). As of November 1979, a federal grand jury in New York City was investigating Vesco’s masterminding an alleged scheme whereby Libyan government officials were to pay off members of the Carter administration to facilitate Libya’s purchase of American C‑130 transport planes; see the New York Times, 4 November 1979. Five months later, in the midst of Jimmy Carter’s reelection campaign, an assistant U.S. attorney announced that a second federal grand jury in Washington had returned no indictments following its investigation of allegations that Vesco had attempted to bribe Carter administration officials to fix his long‑standing legal problems. The grand jury’s foreman, Ralph Ulmer, immediately criticized the incompleteness of the announcement, charging that “the statement is incomplete and thus misleading, which is about par for the course for the Justice Department.” (New York Times, 2 April 1980).

Ulmer had earlier charged that “cover‑up activities are being orchestrated within the Justice Department under the concept that the Administration must be protected at a costs… Among other things information was withheld from the grand jury… a witness was encouraged to be less than candid with the FBI.” (Boston Globe, 30 August 1979.)

SEVENTEEN

WHITE HOUSE HANKY PANKY

Never had Richard Nixon’s White House staff been so preoccupied with narcotics matters as in the summer of 1971. They were obsessed with two projects: a new White House intelligence and enforcement unit as envisioned by the Huston Plan, and a comprehensive narcotics control apparatus, similarly under direct presidential control. The two idees fixes converged in a conspiratorial and political‑criminal network of hitherto unimagined dimensions.

That summer the White House set up the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention alongside the Special Investigation Unit, otherwise known as the Plumbers. Several of the Plumbers also worked on narcotics affairs. The groups’ key figures included:

Egil Krogh (chief Plumber)—who followed John Erlichman (for whose law firm he had worked part time) to the White House in 1968 within months of his graduation from the University of Washington Law School. He was named deputy assistant to the president for law enforcement, and within three years found himself in charge both of Nixon’s narcotics and law enforcement campaign, and of the “Plumbers squad. His single‑minded ambition surfaced in a declaration to the noted psychiatrist and narcotics expert, Dr. Daniel S. Freedman, when the latter refused to support one of Krogh’s programs: “Well, don’t worry. Anyone who opposes us we’ll destroy. As a matter of fact, anyone who doesn’t support us, well destroy.”[1] Krogh would wind up in jail for the break‑in at the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, Dr. Lewis Fielding.

Walter Minnick (temporary Plumber)—a young graduate of Harvard Business School and former agent of the CIA, who joined Krogh’s narcotics staff in spring 1971 and later helped draft the reorganization plan that created the DEA.

John Caulfield (Plumber)—a former agent of the New York City Police Department’s Bureau of Special Services (BOSS), which specialized in narcotics and “monitoring the activities of terrorist organizations.” In the 1960 presidential campaign he had been assigned to protect candidate Nixon in New York City. That and his close relationship with Nixon’s personal secretary, Rose Mary Woods (of eighteen and one‑half minute tape gap fame), gained him a foot in the door of the White House.[2]

Myles Ambrose—the former Customs Commissioner, who was named head of the narcotics campaign’s domestic strike force. He would later leave government service in disgrace.

G. Gordon Liddy (Plumber) ‑a former FBI agent whose narcotics intelligence job at the Treasury Department had been terminated, only weeks prior to his recruitment by the White House, for his outspoken lobbying against gun‑control legislation. Eventually, he would get six‑to‑twenty for his role in the break‑in at the Watergate complex and one‑to‑three for the job at Fielding’s office.

Howard Hunt (Plumber)—a former CIA agent closely connected to the agency‑trained Cuban exiles, many of whom had emerged from Santo Trafficante’s Cuban narcotics Mafia. Hunt was employed as a special advisor on narcotics problems in Southeast Asia. In November 1973 Judge John Sirica would sentence him to two‑and‑a‑half to eight years — reduced from an initial thirty‑five — for the Watergate break-in.

Lucien Conein—a CIA agent, Ed Lansdale’s right‑hand man in Vietnam, and an expert on Southeast Asian narcotics centers and the Corsican Mafia. He was brought into the White House by his old buddy Hunt.

David Young—a young lawyer who put up a sign outside his office, “Mr. Young, Plumber,” when apprised that he would be plugging leaks and that the trade had run in his family. He came to Krogh’s staff from Henry Kissinger’s National Security Council.

It was a strange mix of novices and experienced agents with the most intriguing pasts.

Hunt and Liddy were located in Room 16 of the Executive Office Building, headquarters for the Plumbers group’s secret narcotics missions and other, crooked operations on behalf of the Committee to Re‑Elect the President (CREEP). The Plumbers’ first assignment was the break‑in at the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist.[3] For the break‑in dirty work, Hunt enlisted Bernard Barker, Eugenio Rolando Martinez and Felipe de Diego, three of his Cuban friends who had been involved in the Bay of Pigs invasion. Martinez and de Diego also took part in the CIA’s follow‑up Operation 40, and the ubiquitous Martinez was in on Trafficante‑masterminded boat raids on Cuba.[4]

By the summer of 1971 the White House Death Squad was well on its way. Hunt sought out Barker in Miami for what Hunt called “a new national security organization above the CIA and FBI.” Barker would assemble a force of 120 CIA‑trained exiles for Operation Diamond, which, under cover of narcotics enforcement, would kidnap or assassinate political enemies. Barker signed up.[5]

In the fall of 1971 Hunt asked another of his Cuban friends, Bay of Pigs veteran Manuel Artime, to set up “hit teams” for the liquidation of narcotics dealers. As later revealed, Artime’s primary target was to have been the Panamanian strongman, General Omar Torrijos.[6]

Krogh and his staff, meanwhile, tightened their grip on narcotics control. After the BNDD takeover of customs’ international jurisdiction, Krogh pushed Bureau chief John Ingersoll for results to feed Congress and the press. In September 1971 Krogh was named to direct the newly formed Cabinet Committee on International Narcotics Control. In collaboration with the State Department, BNDD, CIA and Henry Kissinger’s office, the committee coordinated the international struggle against narcotics. State Department narcotics advisor Nelson Gross, chosen to supervise the joint actions, was later sentenced to two years for attempted bribery and income tax evasion.[7]

Egil Krogh was less than satisfied with existing narcotics efforts, especially those of the CIA, whose intelligence reports, according to Ingersoll, were decisive for the work of the BNDD. Krogh wanted the White House instead to handle the BNDD’s intelligence work. Nixon’s staff would then decide which drug traffickers to pursue. Krogh’s dissatisfaction was expressed to Hunt, who immediately proposed an Office of National Narcotics Intelligence (ONNI) where all narcotics intelligence reports would be analyzed and follow‑up actions decided.[8]

Hunt told Krogh he could enlist for the office experienced CIA figures, starting with Lucien Conein at its head.[9] Nixon, however, chose William C. Sullivan instead. Once second to J. Edgar Hoover in the FBI, Sullivan had managed Division Five, which investigated espionage, sabotage, and subversion.[10] He also directed Operation Cointelpro, the bureau’s vendetta against dissident political and cultural groups (such as the Black Panthers), and had been Nixon’s choice to direct the Huston Plan’s elaborate surveillance of U.S. citizens.[11]

Hunt, nevertheless, found a niche for his friend. Conein was assigned to the BNDD as a “strategic intelligence officer,” and came to control overseas narcotics intelligence, originally the domain of ONNI,[12] while Sullivan concentrated on domestic affairs.[13]

The White House now controlled narcotics intelligence at home and abroad. But that still wasn’t enough. Nixon’s staff also sought to control enforcement itself, and that required effective strike forces. In January 1972 the White House set up the Office for Drug Abuse Law Enforcement (ODALE) according to a plan conceived by Gordon Liddy. It became the domestic strike force under Myles Ambrose — whose government career ended with news of his pleasure trip to the ranch of a Texan indicted for narcotics and gun‑running.[14] ODALE soon became notorious for its record of illegal raids, no‑knock entries into private homes, and beatings of innocent people.[15] Some called it the American Gestapo.

Overseas, as well, the White House was dissatisfied with the BNDD’s enforcement powers. Dr. J. Thomas Ungerleider, a member of the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse, noted in a record of his conversations with BNDD officials: “There was some talk about establishing hit squads (assassination teams), as they are said to have in a South American country. It was stated that with 150 key assassinations, the entire heroin refining operation can be thrown into chaos. ‘Officials’ say it is known exactly who is involved in these operations but can’t prove it.”

Hunt, Liddy and others in Room 16 did not confine themselves to narcotics campaigns and political assassinations. On behalf of CREEP they raised campaign funds from more or less shady sources and sabotaged the campaigns of George Wallace, Hubert Humphrey, Edmund Muskie, and George McGovern. Hunt’s CIA colleagues are among those who suspect he spiked Muskie’s lemonade with an LSD-like substance prior to the candidate’s famous tearful speech.[16]

Besides Hunt’s Cubans, the familiar Frank Sturgis, who had earlier taken orders from Santo Trafficante, took on narcotics work and special assignments for CREEP.[17] According to a 1972 FBI report, sources in Miami had claimed Sturgis was then associated with organized crime activities. He later told an interviewer that he had aided Hunt in a 1971 investigation of the drug traffic reaching the U.S. from Paraguay via Panama.[18] He was in on several actions connected with the investigation, which focussed exclusively on Auguste Ricord’s Grupo Frances.[19]

Sturgis was everywhere in the hectic spring of 1972. In May he was among the men who assaulted Daniel Ellsberg on the steps of the Capitol. Later that month he and Cubans including Bernard Barker arranged a Miami demonstration in support of Nixon’s decision to mine Haiphong harbor. Sturgis himself was at the wheel of the truck leading the procession. He helped recruit agitators to disrupt the Democratic national convention, and in the June 17 Watergate break‑ in Sturgis joined CIA/ Trafficante Cubans and White House narcotics conspirators.[20]

As the noted Berkeley researcher Peter Dale Scott put it in 1973: “In my opinion it is no coincidence that the key figures in Watergate — Liddy, Hunt, Sturgis, Krogh, Caulfield ‑ had been drawn from the conspiratorial world of government narcotics enforcement, a shady realm in which operations of organized crime, counter‑revolution and government intelligence have traditionally overlapped.”[21]

In July 1973 Nixon’s narcotics forces were essentially consolidated according to Reorganization Plan Number Two worked out by former CIA agent Walter Minnick and Egil Krogh. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was formed out of the BNDD, ODALE, ONNI and Customs Intelligence. Four thousand operatives, including fifty CIA agents (many of them Cubans from the ODALE hard core), five hundred customs agents and most of the BNDD staff made the DEA a powerful new agency.

Ingersoll of the BNDD, Ambrose of ODALE and Sullivan of ONNI all resigned as John R. Bartels became the DEA’s first director. His was no small task. Earlier rivalries persisted. The strange brew of agents with widely varying backgrounds and assignments made the DEA difficult if not impossible to steer. U.S. narcotics enforcement has a history of corruption, scandal and exposure of agent collaboration with the criminals it has been assigned to police.

Still, no bureau has been as plagued by scandal as the DEA has in seven years of existence. The exposes and charges run the gamut from trafficking in drugs, teamwork with the Mob and protection of major traffickers, to thievery, gunrunning, torture, and assassination of drug traffickers.[22]

When Lucien Conein became the head of the DEA’s Special Operations Branch he allegedly carried out an assassination program after setting up the DEA’s Special Operations Group (DEASOG), under cover of the B.R. Fox Company and housed on Connecticut Avenue in Washington.[23] DEASOG’s twelve members—the Dirty Dozen —were hard‑nosed and experienced Latino CIA agents transferred over to the drug agency for the occasion. Prior to DEASOG, Conein had set up another DEA “intelligence” operation, Deacon I, employing Cuban exile veterans of CIA training camps, who were supervised by thirty other Cubans, all formerly of the CIA’s Clandestine Services.[24]

In response to the claim that DEASOG was a “hit team,” Conein told journalist George Crile: “That is a big ‑‑‑‑‑‑‑ lie. That is bull ‑‑‑‑‑However, a DEA official had told Crile: “When you get down to it, Conein was organizing an assassination program. He was frustrated by the big‑time operators who were just too insulated to get to.” DEA officials also told Crile that “meetings were held to decide whom to target and what method of assassination to employ. Conein then assigned the task to three of the former CIA operatives assigned to the Connecticut Avenue safe house.”[25]

DEASOG shared its Washington office with an old friend and colleague of Hunt and Conein’s from OSS China, the weapons dealing soldier of fortune and specialist in assassination, Mitch WerBell III.26 WerBell told Crile he had been a business partner of Conein’s as late as 1974, and that he and Conein had worked together on providing the DEA with assassination devices.[27] Among WerBell’s other associates were Frank Sturgis, Cuban exile leaders, and Robert Vesco, who, like WerBell himself, has been charged with bankrolling narcotics smuggling.[28] Carlos Hernandez Rumbaut, the bodyguard of Vesco’s close friend and business partner, former Costa Rican President Pepe Figueres, is a former Conein agent who fled the country to avoid imprisonment on a drug conviction.[29] He has reportedly reentered the U.S. twice with a U.S. diplomatic passport.[30]

Assassination, it can be argued, became a modus operandi under Richard Nixon. The CIA carried out assassination and extermination campaigns in Vietnam, Guatemala, Argentina, and Brazil[31]—aided in Latin America by the local Death Squads. The White House appears to have‑sponsored a secret assassination program under cover of drug enforcement. It was continued by the DEA, which seemingly overlapped with the CIA in political rather than drug enforcement.

Until 1974 the training of torturers and members of Latin American death squads came under the auspices of the CIA and USAID’s Office of Public Safety. Some 100,000 Brazilian policemen, for example, were trained and 523 of them were chosen for courses in the U.S.A.[32] They were trained at the International Police Academy in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. and at a secret CIA center in the same city on R Street, under cover of International Police Services, Inc. When school was out the prize pupils returned home to work, beside CIA advisors, as functionaries or torturers in such effective repression apparatuses as Sao Paulo’s Operacao Bandeirantes.[33] Many would moonlight with the Death Squads.

After Tupamaros guerillas kidnapped and killed U.S. police advisor Dan Mitrione in Uruguay, Washington’s schools for foreign police came into the limelight and Congress cut off their funding.[34] Nonetheless, the training program and direct assistance and supervision continued. A 1976 investigation authorized by Senator James Abourezk revealed that the U.S. torture academies had not in fact been completely closed down. According to Jack Anderson, Abourezk found such a school had been in operation since 1974 in Los Fresnos, Texas at the site of a former “bomb school.” Another journalist, William Hoffman, later confirmed the existence of a school for torture in Los Fresnos, which had since moved to Georgia, where it was known as the Law Enforcement Training Center.[35] Interestingly, Conein’s friend WerBell runs his own large training center in Georgia, The Farm. It’s used for, among other things, the training of law enforcement officers.[36]

Much of the old police support apparatus was simply transferred to AID’s International Narcotics Control program (INC), which really spelled DEA. In 1974 the DEA had some 400 agents in Latin America, or roughly the number of advisors recalled from the OPS program. INC’s budget for technical equipment abroad, meanwhile, jumped from $2.2 million in 1973 to $12.5 million in 1974.

The politics of the new drug effort were exposed when, in 1974, the man behind Argentina’s death squad (the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance), Social Minister Lopez Rega, appeared on TV with U.S. Ambassador Robert C. Hill to publicize the two nations’ antinarcotics collaboration with the words: “Guerillas are the main users of drugs in Argentina. Therefore, the anti‑drug campaign will automatically be an anti‑guerilla campaign as well.”[31]

It’s striking how close the various extermination and repression campaigns have been to the narcotics traffic. The Meo Army deployed by the CIA in Laos smuggled large quantities of opium. Lopez Rega and his Argentine AAA henchmen were eventually exposed as keys to a cocaine ring.[38] One of the chief AAA hatchet men, Francois Chiappe, was a lieutenant in the Ricord/David heroin network.[39] Paraguay’s most ruthless high‑ranking officers were exposed as heroin profiteers. Christian David took part in extermination campaigns in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. Operacao Bandeirantes’ chief, Sergio Fleury, and several of his colleagues pocketed large protection payoffs.[40] Fleury’s number two man in the Sao Paulo Death Squad, Ademar Augusto, de Oliveira, alias Fininho, fled to Paraguay after he was charged with murder. There, under the name Irineu. Bruno da Silva, he worked for the Ricord gang.[41] When David’s successor, the Brazilian narcotics dealer Milton Concalves Thiago, alias Cabecao (The Brain), was arrested in 1975, it was learned that he had been paying off the entire Rio de Janeiro Death Squad, which included four narcotics police lieutenants .42 And finally as we go to press we learn that the dictator, Pinochet, assumed control of Chile’s cocaine trade, then turned it over to his secret police, DINA, which shared the profits with its Cuban exile henchmen.[43]

The political violence set in motion by the White House narcotics offices ran smoothly. But what of actual drug enforcement? From its inception it focused on dismantling the French narcotics network. When that was done, America would be free of the heroin plague, or so said Nixon and his staff. Reports of increasing amounts of heroin from Southeast Asia and Mexico were obscured by the great public relations campaign on the struggle against the Corsicans.

The Turkey/ Marseilles/ U.S. heroin pipeline was indeed shut down, and the French Corsican Mafia was almost totally decimated. But major new suppliers in Southeast Asia and South America were left untouched — despite warnings and reports — and despite the many CIA “experts” on the Latin American drug scene. Not only were most major heroin suppliers in the two regions left alone, they were protected. And they were aided by the arrest of small‑time competitors.

At home the story was nearly the same. ODALE and DEA nabbed only minor distributors and sidewalk pushers.

pps. 159-169

–[Notes]–

1. L. Lurie: The Impeachment of Richard Nixon (Berkeley, 1973).

2. J.A. Lukas: Nightmare (Viking, 1976).

3. It is interesting to speculate whether Ellsberg’s knowledge of top‑secret operations in Vietnam touched on narcotics. His supervisors in Southeast Asia had been General Lansdale and Lieutenant Colonel Conein. Ellsberg and Conein were apparently quite close in Vietnam. Conein reportedly saved Ellsberg’s life when the latter got romantically involved with the mistress of an Corsican Mafia capo. The gangster threatened to kill Ellsberg. Conein, in turn, told the gangster it would lead to his own funeral and war between the CIA and the Corsicans ‑see J. Hougan: Spooks (William Morrow, 1978).

4. See chapter fifteen.

5.1977 CBS interview of Bernard Barker; see also G. Crile III in the Washington Post, 13 June 1976.

6. J. Marshall: “The White House Death Squad,” Inquiry, 5 March 1979.

7. E.J. Epstein: Agency of Fear (Putnam, 1977).

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. D. Wise and T.B. Ross: The Invisible Government (Random House, 1964).

11. S. Blumenthal: “How the FBI Tried to Destroy the Black Panthers,” in Government by Gunplay, S. Blumenthal and H. Yazijian, eds. (New American Library, 1976).

12. H. Messick: ‑Of Grass and Snow (Prentice‑Hall, 1979).

13. A 1971 New York investigation revealed that 47 percent of the city’s 300,000 addicts were Black, 27 percent Hispanic and only 15 percent White‑see C. Lamour and M.R. Lamberti: Les Grandes Maneuvres de l’0pium (Editions du Seuil, 1972); i.e., there were some 150,000 Black addicts in New York City alone. Still, Nixon named as director of ONNI, William C. Sullivan. The man who had planned and executed Operation Cointelpro would now battle the forces doping the potentially troublesome elements of the Ghetto. Ironically, Malcolm X and the Panthers, prime Cointelpro targets, had been the only ones to make significant headway against ghetto drug addiction.

14. T. Meldal‑Johnsen and V. Young: The Interpol Connection (Dial, 1979).

15. Epstein, op. cit.

16. M. Copeland: Beyond Cloak and Dagger (Pinnacle Books, 1974).

17. H. Kohn: “Strange Bedfellows,” Rolling Stone, 20 May 1976.

18. True, August 1974.

19. In his book Cygne (Grasset, 1976), intelligence agent Luis Gonzales‑Mata describes being assigned a special task by CIA agent “Robert Berg.” He was to convince the Paraguayan dictator Stroessner that Ricord was behind a planned coup attempt against him financed with heroin from Red China. Stroessner was in a bind, since he very well knew that the source of the heroin was not Red China but his bosom buddies in Taiwan.

20. C. Bernstein and B. Woodward: All the President’s Men (Warner Books, 1975).

21. P.D. Scott: “From Dallas to Watergate,” Ramparts, November 1973.

22. U.S. Justice Department DeFeo Report, 1975; the list of DEA abuses has recently been expanded to include a computerized information system covering 570,000 names (a number which may be compared with the 8000 federal drug arrests each year)‑see E. Rasen: “High‑Tech Fascism,” Penthouse, March 1980.

23. Hougan, op. cit.

24. Ibid.

25. Crile, op. cit.

26. Another OSS China hand, Clark McGregor, replaced John Mitchell as the head of CREEP.

27. Crile, op. cit.

28. T. Dunkin: “The Great Pot Plot,” Soldier of Fortune, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1977;

L.H. Whittemore: Peroff (Ballantine, 1975).

29. Hougan, op. cit.

30. Crile, op. cit.

31. Cuban exiles took part in an extermination campaign in Guatemala between 1968 and 1971. According to Amnesty International, 30,000 people were murdered there between 1962 and 1971, most of them in the last three years. Similarly, anti‑Castro Cubans had their hand in the Argentine AAA’s murder campaign believed to have claimed 10,000 lives. In Brazil the Sao Paulo Death Squad alone is estimated to have assassinated 2000 between 1968 and 1972, while many others perished in the torture chambers.

32. Skeptic, January/ February 1977.

33. A.J. Langguth: Hidden Terrors (Pantheon, 1978). 34. Ibid.

35. Gallery, May 1978.

36. Dunkin, op. cit. Among other antiterrorism trainees at WerBell’s camp in Powder Springs have been several members of U.S. presidential candidate Lyndon Larouche’s U.S. Labor Party. The Marxist turned extreme rightist and anti‑Semitic U.S. Labor Party has voluntarily sent the FBI and local police forces “intelligence” reports on left wing movements, and regularly exchanges information with one Roy Frankhouser, the self‑proclaimed Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan in Pennsylvania and active member of the American Nazi Party — see the New York Times, 7 October 1979.

37. P.Lernoux: “Corrupting Colombia,” Inquiry, 30 September 1979. In July 1978, DEA chief Peter Bensinger strongly recommended that Colombian authorities militarize the Guajira Peninsula, home of the marijuana/cocaine traffic. Two months later, newly elected (and current) President Julio Cesar Turbay issued a security statute empowering the military to arrest any Colombian deemed subversive, without recourse to habeas corpus or other constitutional guarantees. In April 1980, the Colombian Army was about to abandon its U.S.‑financed multi‑million dollar drug war, its failure connected, no doubt, to an estimated $110 million in protection money distributed annually by the smugglers (New York Times, 3 April 1980). Meanwhile, the military has assumed the dominant position in what was one of Latin America’s few remaining democracies. U.S. military aid to Colombia — where, according to Amnesty International’s April 1980 report, military personnel torture political prisoners in thirty‑three locations throughout the country, resorting to fifty identifiable techniques ‑totalled $155 million between 1946 and 1975; 6200 Colombian military personnel were trained by the U.S. in the same period (N. Chomsky and E.S. Herman: The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism, South End Press, 1979). U.S. military aid for 1979 was $12.7 million, the highest amount in Latin America.

38. Latin America, 19 December 1975.

39. L’Aurore, 31 May 1976; Liberation, 19 July 1976.

40. Le Nouvel Observateur, 21 May 1973; A. Lopez: L’Escadron de la Mort (Casterman, 1973); H. Bicudo: Meu Depoimento sobre o Esquadrao da Morte (1976).

41. Le Nouvel Observateur, 21 May 1973. 42. Diario, de Noticias, 7 May 1975. 43. See the foreword, footnote 52.

to be continued…

Watergate Exposed: How the President of the United States and the Watergate Burglars Were Set Up (as told to Douglas Caddy, original attorney for the Watergate Seven), by Robert Merritt is available at TrineDay, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, The Book Depository, and Books-a-Million.