Allegations regarding “Butch” Merritt, Watergate, Intelligence Agencies and “Crimson Rose,” Vol. XX

Endgame – Part Seven

Written (and first posted) by Kris Millegan, April 17, 2011

David Rockefeller came in, apparently to induce me to let the shah come to the United States. Rockefeller, Kissinger, and Brzezinski seem to be adopting this as a joint project. – Jimmy Carter, White House Diary, April 9 1979

In the midst of Watergate, Richard Nixon sent career CIA official Richard Helms to Iran as the US Ambassador in January of 1973. Helms had gone to prep school with the Shah in Switzerland and the CIA had put the Shah in power in 1953. Helms served as Ambassador for three years.

The next, and our last accepted, Ambassador to Iran was William H. Sullivan, he had been the ambassador to Laos from 1964-1969, and had personally supervised the most intensive bombing of that country. During this same time opium trafficking in Laos was being supported by American “interests.” Infamous CIA agent Theodore Shackley was the CIA Chief of Station in Laos from 1966-68, and then moved on to Saigon where he served as Station Chief until 1972.

Ted Shackley had an interesting career, from Wiki:

Miami and the Cuban crisis

Shackley was station chief in Miami, Florida during the period of (1962 – 1965). While heading the CIA office (known as “JMWAVE”) shortly after the Bay of Pigs Invasion, Shackley dealt with operations in Cuba (alongside Edward Lansdale). JMWAVE employed more than 200 CIA officers, who handled approximately 2,000 Cuban agents. These included the famous “Operation Mongoose” (aka “The Cuban Project”). The aim of this was to “help Cuba overthrow the Communist regime” (of Fidel Castro Ruz). During this period as Miami Station Chief, Shackley was in charge of around 400 agents and general operatives (as well as a huge flotilla of boats), and his tenure here encompassed the “Cuban Missile Crisis” of October 1962. {emphasis added]

Vietnam, Laos and the “Phoenix Program”

In 1966, Shackley moved on to the Vietnam War, becoming the CIA station chief in Laos between 1966-1968, where he directed the CIA’s secret war of pitting the Hmong villagers against Vietcong who used the Ho Chi Minh Trail. He also helped coordinate local army efforts against the Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese Army in the northern regions of Laos.

He then moved on to become station chief for Vietnam (in what was then Saigon) in 1968. Despite popular opinion Shackley did not in fact run the Phoenix Program. Phoenix was alleged to be an assassination campaign aimed at members of the Viet Cong infrastructure. Allegations that thousands of civilians were killed is not supported by historical evidence. After the US Bureau of Narcotics’ “Operation Eagle” busted a drug-running scheme in 1970, several of the Cuban-Americans involved in the Bay of Pigs Invasion came to work for Shackley and Donald Gregg in Vietnam, including Felix Rodriguez. The Phoenix Program was eventually handed over to the U.S. and South Vietnamese armies. Shackley served in Vietnam through February 1972 when he returned to Langley, Virginia. [emphasis added]

Western Hemisphere Division and Chile

From 1972, Shackley ran the CIA’s “Western Hemisphere Division”. When Shackley took over the Western Hemisphere division in 1972, one mission for him was “regime change” in Chile.

One of Shackley’s jobs whilst in charge of the CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division was to discredit an ex-CIA officer believed to have become under control of the KGB, Philip Agee who was writing an “expose” on the CIA entitled Inside The Company. After Shackley’s best efforts to discredit Agee, the parts of the book that would have caused most damage to the reputation of the CIA were not included.

Deputy Director of Covert Operations

In May 1976, Shackley was made Deputy Director of Covert Operations, serving under director George H.W. Bush, before officially retiring from the organization in 1979. However, it has been widely reported that in reality he was forced out of the organization by Bush’s successor as Director, Stansfield Turner. Turner disapproved of Shackley’s close involvement with agent Edwin P. Wilson and ex-CIA employee, Frank Terpil. [emphasis added]

From Wiki:

Opium in Iran is widely available, and the country has the highest per capita number of opiate addicts in the world at a rate of 2.8% of Iranians over age 15. The Iranian Government estimates the number of addicts at 2 million. Opium and heroin from Afghanistan and Pakistan –known collectively as the Golden Crescent– pass through Iran’s eastern borders in large amounts. Total annual opium intercepts by the Iranian authorities are larger than in any other country, but the government admits that they can only intercept a tiny proportion of the thousands of tonnes that are trafficked through Iran every year. Opium costs far less in Iran than in the West, and is even cheaper than beer. In Zahedan, an Iranian town near the Pakistani border, 3 grams of opium can be purchased for 10,000 Iranian rials, equivalent to $1 USD, and 1kg costs the equivalent of $330. In Zabol, $1 buys 5g of Afghan opium. In addition to having a low price, opium is popular because alcohol is haram (forbidden in Islam), and more tightly controlled by the Iranian Government. According to official Iranian government reports, within Tehran the daily consumption of opium is 4 metric tons. According to UNODC estimates, 450 metric tons of opium are consumed in Iran each year. [emphasis added]

Opium and the CIA, they appear to go well together. Traditionally, Iran has been one of the world’s largest suppliers of opium. In the 1949 United Nations report about the world production of opium, Iran was named as “one of the chief opium-producing and exporting countries” in the world.

Ok, back to Watergate. Nelson Rockefeller didn’t get to be President. After the “Halloween Massacre,” he wasn’t even on the ticket anymore. But brother David had a “friend,” Jimmy Carter, who could keep the seat warm, and if Jimmy wasn’t co-operative he could easily be “dismissed.”

Left to right: Andy Messing Jr., Edwin Lansdale, Medadro Justinano, John Singlaub and Oliver North

According to the Washington Post, North “was already Lansdale-ized when he reached the NSC.” How did that happen?

From http://peacemagazine.org/archive/v04n2p09.htm:

The Secret Team, Part III: Chaos in Laos

The Secret Team Enters South-East Asia

By John Bacher

More bombs were dropped on Laos between 1965 and ’73 than the US had dropped on Japan and Germany during World War II. More than 350,000 people were killed. The war in Laos was a secret only from the American people and Congress. It anticipated the sordid ties between drug trafficking and repressive regimes that have been seen later in the Noriega affair.

AFTER THE CLOSING DOWN OF the United States’s secret war in Cuba, CIA agents Theodore Shackley and Tom Clines were sent eastward to set up a far more massive secret war in Laos. Like its previous “Operation Success,” “Mongoose” and “JM/Wave” assignments, the team was presented with another “mission impossible” — to prop up a reactionary U.S. client state with little indigenous popular support. That the mission succeeded as well as it did, from 1965 to 1973, was only possible because of massive narcotics smuggling and saturation bombing which tended to overshadow any national foreign policy objective.

Prior to the arrival of the Secret Team in Laos, the U.S. had a sordid history of the destruction of neutralist Laotian governments with broad political support, since the country received its independence from France in 1954. The CIA engineered coups in 1958, 1959, 1960, and possibly on other occasions, as William Blum has documented in his The CIA: A Forgotten History. Such manipulation had the effect of driving the Pathet Lao (Communist Party) out of the political arena and into military conflict in alliance with North Vietnam. U.S. President John F. Kennedy did have the intelligence to see the absurdity of this situation and obtained a coalition government with the Pathet Lao backed by international agreement. This neutral regime was, however, overthrown in 1964 by a right wing coup, giving effective control to reactionary generals with close ties to the CIA.To stabilize this regime with so little popular support, the CIA sent Theodore Shackley and Tom Clines to Laos in 1964.

Unlike the war in Vietnam, the secret war in Laos remained in the hands of the CIA and avoided direct deployment of U.S. troops. This lack of American casualties tended to hide its massive scale. After the war’s end, the New York Times observed that “some 350,000 men, women and children have been killed, it is estimated, and a tenth of the population of three million uprooted.” Between 1965 and 1973, more than two million tons of bombs were dropped on Laos — far more than the U.S. had dropped on both Japan and Germany during World War II. This bombing was applied to all regions controlled by the Pathet Lao. A former American community worker in Laos, Fred Branfam, described how “village after village was levelled, countless people burned alive by high explosives, or by napalm and white phosphorous, or riddled by anti-personnel bomb pellets.” In order to wreck the economy in the Pathet Lao area, the U.S. dropped millions in forged currency. At the end of the war in Laos, the Plain of Jars resembled a lunar landscape marked by bomb craters,”stark testimony to the years of war that denuded the area of people and buildings.” Irrigation works collapsed and so many water buffalo had been killed in the war that farmers had to harness themselves to the plows to till fields. Unexploded ordnance are still killing and hampering food production. Such weaponry includes fragmentation weapons with explosives and steel bits released from large canisters.

THE ROYAL LAO ARMY HAD PROVEN unreliable to prop up John Foster Dulles’s puppet American regimes in the ’50s, which were often overthrown by nationalistic officers. Therefore Shackley and Clines developed their own secret army, based on the discontented Meo tribal minority and financed by the narcotics trade. Meo villages that refused to send troops to fight in this secret army were bombed by the U.S. Air Force, as Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman point out in After the Cataclysm. To suit U.S. strategic needs, villages were relocated. Besides 15,000 Meo tribesmen, the secret army included 15,000 mercenaries from Thailand, and U.S.-trained soldiers from South Vietnam, Taiwan, South Korea and the Philippines. The New York Times quipped that the “Secret Army” was secret only from “the American people and Congress.” American advisers killed in Laos were reported to have died in Vietnam.

ONE objective of Shackley and Clines was to monopolize the opium trade in Laos for their Meo ally, Van Pao. In 1965 Van Pao’s opium trafficking competitors were assassinated.

After the end of the Indochina war, the CIA admitted that “certain elements” of its war organization had been involved in opium smuggling. As Henrick Kruger points out in The Great Heroin Coup (Black Rose, 1980), the CIA was forced to admit this because of reports of returning U.S. veterans. One report, by highly-decorated Green Beret Paul Withers, explained that one of his main tasks had been “to buy up the entire crop of opium” of the Meo tribe. About once a week an Air America (a CIA owned company) plane, he reported, “would arrive with supplies and kilo bags of opium, which were loaded on the plane. Each bag was marked with the symbol of the tribe.” Air American flights were exempted from normal customs inspections. In 1971 some 60 kilos of heroin (worth $13.5 million) were seized from the briefcase of the chief Laotian delegate of the World Anti-Communist League.

Shackley and Clines also developed a program to use their secret army for “unconventional warfare” activities, including political assassinations. This is detailed in the lawsuit of the Christic Institute. In 1966 a multi-service operation, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam — Special Operations Group (MACV-SOG) was formed. From 1966-1968 this group supported the assassination activities of the secret army and was commanded by future World Anti-Communist League president and Contra fundraiser, General John K. Singlaub. Serving under Singlaub in Laos in 1968 was the then Second Lieutenant Oliver North. [emphasis added]

From 1968 to 1971 Theodore Shackley and Tom Clines supervised the Special Operations Group in Laos. The secret army assassinated over 100,000 noncombatant villagers: mayors, bookkeepers, clerks and other political figures in Laos, Cambodia and Thailand. These killings established a foundation of terror for the Laotian government, undermined Prince Norodom Sihanouk’s efforts to steer a neutral course for Cambodia, and discouraged the growth of democracy in Thailand. The style of terror resembled the random killings of Colonel Kurtz’s Montagnards in the film Apocalypse Now. Unfortunately movie watchers are deceived into thinking such madness would bring official punishment instead of promotions.

The antics of the Secret Team in Laos would be a prelude to even more destructive activities in Vietnam, where their program of narcotics smuggling and assassination would develop even greater scope. This war was too massive to let the brunt of the fighting to fall to tribal minorities and foreign mercenaries, causing America to officially enter Southeast Asia.

The U.S. client state’s government became so deeply involved in illegal activities, such as the heroin trade and thievery, that it more resembled an organized crime syndicate than a coalition of conservative political parties. The terrorist operations of the Secret Team in Vietnam, such as the infamous Phoenix Program, destroyed both the “third force” and the communist-led National Liberation Front, tending to make the domination of the area by North Vietnam the inevitable outcome of the conflict.

Carter needed to go. From http://www2.fiu.edu/~mizrachs/october-surprise.html:

IV. The Hostage Rescue Mission

On April 23, 1980, an abortive Iranian hostage rescue mission took place, conducted under the utmost secrecy. The plan was to storm the American embassy in Tehran, and bring home the hostages.

8 helicopters, 6 C-130 transport planes, and 93 Delta force commandoes secretly invaded Iran. They were to rendezvous at a place in Iran they called Desert One, move out to another point called Desert Two, and then go on to Tehran to rescue the hostages. But Delta force never made it to Desert Two or Tehran. The mission was aborted after three of the eight helicopters failed, on the way to Desert One. The operation was a miserable failure, resulting in an accident that caused the loss of 8 American lives. Later investigation revealed a surprising level of negligence.

Just before the rescue mission took place, several other countries had finally agreed to level economic sanctions on Iran. Some of them agreed to the sanctions because they thought that if they did, the U.S. would not take any military action. They were quite irate when they heard about the rescue mission after the fact.

At least three central figures in the Iran-Contra Scandal were involved with the Iranian hostage rescue mission: Secord, Hakim, and North.

General Richard Secord helped to organize the abortive rescue mission. After the first mission failed, he was the head of the planning group that eventually decided against another rescue attempt. Because the whereabouts of the hostages were unknown, the second rescue attempt (the October Surprise that the Reagan-Bush campaign was so worried about) never happened.

Secord was later suspended from his Pentagon post because of the EATSCO probe. EATSCO is a company that belongs to Edwin Wilson, the CIA operative who is currently serving time in a federal maximum-security prison for, among other things, secretly supplying 43,000 pounds of plastic explosives to Kadaffi. [emphasis added]

In 1981, he became Chief Middle East arms-sales adviser to Secretary of Defense Casper W. Weinberger.

Albert Hakim is a wealthy arms merchant, an Iranian exile, and CIA informant, who had a “sensitive intelligence” role in 1980 hostage rescue. He worked for the CIA near the Turkish boarder, handling the logistics of the rescue mission in Tehran. Hakim purchased trucks and vans, and rented a warehouse on the edge of Tehran to hide them in until they were needed for the operation. Unexpectedly however, he skipped town the day before the rescue mission. Later on, in July, 1981, Hakim approached the CIA, with a plan to gain favor with the Iranian government by selling it arms.

Oliver North led a secret detachment to eastern Turkey. He was in the mother ship on the Turkish border awaiting the cue from Secord to fly into Teheran and rescue the hostages. [2] [25] After the first aborted rescue mission, he worked with Secord on a second rescue plan.

According to the October Surprise theory, Secord, North and Hakim did not intend Desert One to carry through. The miserable failure of Carter’s Desert One rescue attempt may have been deliberate.

From wiki:

Major General Richard V. Secord, Retired, was a United States Air Force officer convicted for his involvement with the Iran-Contra scandal only to be exonerated after a 1990 Supreme Court case found the statute used to be illegal. He was born in LaRue, Ohio in 1932.

He graduated from West Point in 1955 and was then commissioned in the USAF. He was President of Stanford Technology Trading Group Intl., also known as the “Enterprise”, a company involved with arms sales to Iran during the Reagan presidency.

Since 2002, retired General Secord has held the position of CEO and Chairman of the Board at Computerized Thermal Imaging.

Laos

Richard Secord was involved in the Secret War in Laos during the Second

Indochina War. He flew close air support missions in VietNam in 1962, and was

the CIA chief of tactical air support in Laos on detail from the USAF in 1966,

67 and 68. See his book, “Honored and Betrayed” published in 1992.

Iran-Contra

Secord was

the USAF Chief of the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) in Iran from

1975-78. In this capacity he managed all USAF military assistance

programs in Iran as well as some US Navy and Army programs. During this time he

oversaw Project Dark Gene and Project Ibex. 9emphasis added]

Again from http://www2.fiu.edu/~mizrachs/october-surprise.html:

V. The 1980 Presidential Election

The CIA helped the Reagan-Bush campaign to win the 1980 presidential election. Congressional investigations have revealed that active-duty CIA officers were working with the campaign.

Former agents of FBI and CIA used to gather political information from their colleagues still active in the two agencies. Under the direction of Reagan’s campaign chairman, William Casey, Reagan’s forces had infiltrated Carter’s camp with one or more spies. Casey and Bush were very popular with the CIA. William Casey operated an old-boy network of spies, and George Bush was director of the CIA during the Nixon Administration.

The CIA was down on Carter. Many agents were outraged by Carter-appointed CIA director, Stansfield Turner. He had had removed about 600 people from their jobs in covert operations, and he disciplined Theodore Shackley and Thomas Clines, two popular and powerful agents who were involved with some unsavory operations. (They were mixed up with Edwin Wilson, who sold explosives to Libya, and was associated with Secord through EATSCO.) [emphasis added]

The spies associated with the Reagan-Bush campaign played an important role on the Debategate scandal. The Reagan campaign had somehow acquired copies of briefing books used by Carter to prepare for the 1980 presidential debate.

On October 20, 1980, almost a week before the Carter-Reagan debate, Wayne H. Valis, a former aide to Mr. Reagan, sent debate briefings acquired from Carter’s campaign staff, to Jim Baker, and David R. Gergen.

When the Debategate scandal broke in 1983, Edwin Meese 3rd and Michael K. Deaver denied any knowledge of political espionage in the 1980 presidential race. Neither of them remember anything about Carter’s briefing book, or have any documents or records pertaining to the incident.

Meese insisted that the House subcommittee investigating the conduct of the 1980 presidential campaign have only limited access to the documents the White House wanted to provide, for fear that the committee would stumble upon important but unrelated documents. attempt to set up a criminal investigation was blocked by the Justice Department.

The Reagan-Bush campaign was afraid Carter would rescue the hostages and win the election. Before the election, there were many rumors and security leaks about “October Surprise” hostage rescue attempt. Richard Werthlin, Reagan-Bush 1980 presidential campaign pollster, determined that an “October surprise” would end their chances of winning the election.

On April 20, 1980, days before the actual mission, Mike Copeland ran a hypothetical hostage rescue story in the Washington Star that almost exactly predicted the real thing.

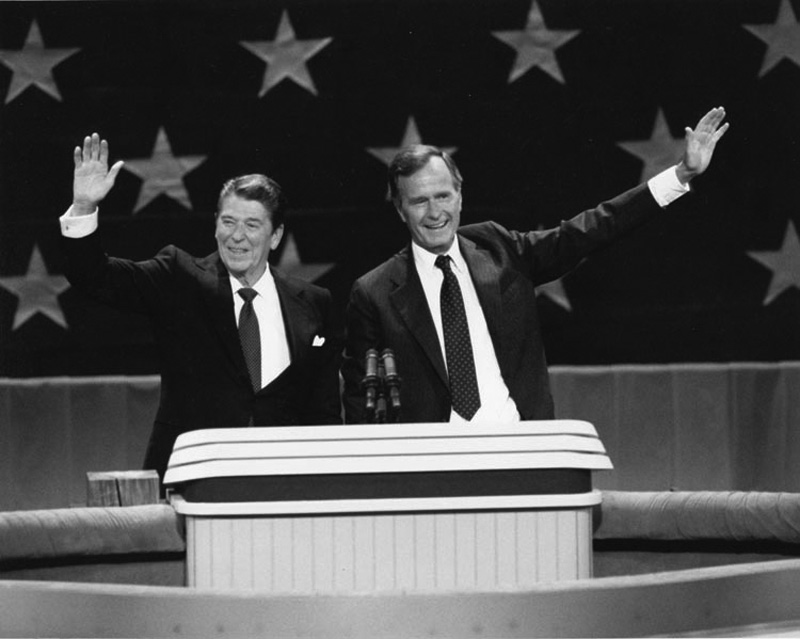

Members of the Reagan-Bush campaign formed the October Surprise Working Group, to keep Carter from bringing hostages successfully home. Richard Allen, Reagan’s foreign policy advisor, was the head of the group. The group included William Casey, Reagan’s 1980 campaign manager, who was later appointed CIA director. Casey was at the heart of the Iran-Contra Scandal, and died before he could testify. The group also included Vice Presidential candidate George Bush, who was eventually elected President of the United States in 1988.

Bush did not have any campaign or public appearances from the 21st to the 27th of October, a week before the election. (Why would they want to keep him out of sight before the election, like they did Dan Quayle?)

According to the October Surprise theory, members of the Reagan-Bush campaign cut a secret deal with the Ayatollah Khomeini, to keep the hostages from being released before the November 4, 1980 presidential election.

Richard Allen met with Robert McFarlane, and an alleged Iranian emissary, in early October 1980, in Washington D.C. They allegedly made a deal to delay release of the hostages until after the election. McFarlane and Allen acknowledge the meeting, but deny that a deal was cut.

Barbara Honegger, a researcher with the Reagan-Bush campaign in 1980, recalls being told then that “Dick cut a deal.” i.e. Richard Allen. Mansur Rafisadeh, former Chief of SAVAK (the Shah’s secret police), and CIA informer, said CIA elements loyal to Reagan arranged a deal to keep the hostages in Iran until Reagan was in the White House. [3] [25] Abol Hassan Bani-Sadr, president of Iran at the time of the alleged deal, said the meeting took place some time during the last two weeks in October 1980, and that Allen and McFarlane met with Hashimi Rafsanjani, speaker of the Iranian parliament, who was the main Iranian contact in subsequent secret arms trading revealed by the the Iran-Contra Scandal.

An investigative subcommittee chaired by Representative John Conyers, Jr. (D-Mich.) is looking into contacts between Iran and the 1980 Reagan-Bush campaign.

VI. The Release of the Hostages

In October 1980, the Carter Administration finally negotiated an agreement between the US and Iran, to unfreeze Iranian assets for the return of the hostages. As a result, the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal is set up at the Hague.

On October 22, the Iranians’ persistent demand of U.S. weapons was suddenly dropped. Bani-Sadr says the demands were dropped because there were two separate agreements: the official one with Carter in Algeria, and the secret one with the Reagan campaign, that the hostages should not be released during Carter’s Administration. In return, Reagan would give them arms.

On Jan 20, 1981, Ronald Reagan was sworn in as President of the United States. The hostages were released moments afterwards.

Endgame … as far as Watergate, but many more games are to be played.

to be continued…

Watergate Exposed: How the President of the United States and the Watergate Burglars Were Set Up (as told to Douglas Caddy, original attorney for the Watergate Seven), by Robert Merritt is available at TrineDay, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, The Book Depository, and Books-a-Million.