Allegations regarding “Butch” Merritt, Watergate, Intelligence Agencies and “Crimson Rose,” Vol. XII

The Dynamics of Sophistication – Part Three

Written (and first posted) by Kris Millegan, March 29, 2011

At no time will the CIA be provided with more equipment, etc., than is absolutely necessary for the support of the operation directed and such support provided will always be limited to the requirements of that single operation. — President Dwight Eisenhower, NSC 10/2

Ike, JFK, Earl Warren, LBJ and Nixon at JFK’s Inaugural

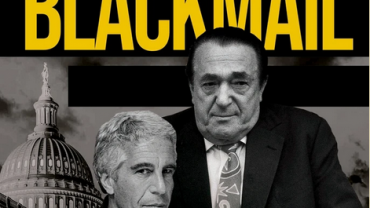

How do “interested parties” turn a republic into empire? It takes time, a few twists and turns behind the scenes (psy-ops), and “grease.” The grease is blackmail.

How does one gather the material for blackmail? You can be at the “wrong” place at the right time, and discover a “terrible” secret. Or by gathering information surreptitiously, or by using “secure” reservoirs of private information held either by commerce or government.

Watergate was one of the psy-ops on the road to empire. A very convenient stop, much was accomplished. And “they” got rid of Nixon, while weakening the Office of the President of the United States.

The excerpt below shows how “they” got rid of a foreign president, from Fletcher Prouty’s JFK, The CIA, Vietnam, and the Plot to Assassinate John F. Kennedy:

… on an inside page of the New York Times on July 25, 1985, a tiny two-inch article, datelined Zaragoza, Spain, describing one of these Cold War battles, being fought with these secret tactics.

TWO SPANISH OFFICERS SENTENCED FOR ROLES IN FAKE EXECUTIONS

ZARAGOZA, Spain, July 24 (UPI)- Two army officers who herded villagers into a public square for mock executions were sentenced today to prison terms of four and five months, military authorities said.

A military tribunal ruled Tuesday that officers, Capt. Carlos Aleman and Lieut. Jaime Iniguez, had been overzealous in carrying out orders. ‘They were ordered to stage a mock invasion of a town and to make it as realistic as possible, but they went too far,” said a Defense Ministry spokesman, Lieut. Jesus del Monte.

This bizarre incident occurred in Spain. Similar events, using the same tactics, take place somewhere in the world almost daily, despite the apparent demise of the Cold War. They have one unique characteristic, seldom if ever seen in regular warfare, that sets them apart. Incidents such as this one, reported by the Times, serve to incite warfare rather than to bring it to an end. To give the age-old concept new meaning, “They make war… out of practically nothing.”

The methods used in Spain are almost precisely those used by the CIA in, among other cases, the Philippines in the early 1950S and Indochina from 1945 to 1965. These will be discussed in later chapters. It is important to note that tens of thousands of foreign “paramilitary” and Special Forces troops have been trained at various U.S. military bases under CIA supervision and sponsorship. Some of this training is highly specialized, using advanced weapons and war-related material. Some of it takes place at American universities and even in manufacturing plants, where advanced equipment for this type of warfare is being made.

The Spanish application of this tactic of the secret war is interesting and threatens us all. In this case, the two army officers had been ordered to attack a town, with regular Spanish troops (albeit some of them disguised as natives), and to make it look and feel realistic. As undercover warriors, they were trained to do this. (No doubt, some were trained in the United States, where many of the weapons, activities, and techniques mentioned below are used in training.) Under other conditions at other times, these same t rained men might have been told to hijack a civilian aircraft; they might have been told to set up a mock car-bombing; they might have been told to run a mock hostage operation. There is no difference. The only military objective of these battles, and of this type of global conflict, is to create the appearance of war itself.

Now, the Spanish, for reasons of their own, had decided to teach this town a lesson. To initiate this campaign, a psychological-warfare propaganda team arrived in town. They put up posters, made inflammatory speeches in the village square, and showed propaganda films on the walls of buildings at night to stir up the village, warning of the existence and approach of a band of “terrorist-trained insurgents.” That night, as the movies were being shown before the assembled villagers, a firefight kit, prearranged to explode in sequence to resemble a true skirmish, was detonated on a nearby hillside. Flares and rockets filled the sky. A helicopter gunship or two joined the mock battle scenario. By the time this Special Forces PsyWar team left that town, the whole region had been alarmed by the presence of these “insurgents, ” The stage was set for the “mock invasion of the town,” as ordered.

A few nights later, these two Spanish army officers (was the CIA involved?) divided their regular force into two groups: (a) the pseudo-insurgents and (b) the loyal regular forces. The “insurgents” took off their uniforms and donned native garb, the uniform of the “Peoples’ Insurgents.” Then they faded into the darkness and began to attack the town. First there was sporadic gunfire. Then some buildings went up in flames. Several big explosions occurred, and a bridge was blown up. The “insurgents” attacked the town as the villagers fled into the night. There was more gunfire, more burning and explosions. The “terrorists” looted the town and fired into the woods where the townspeople were hiding.

As the sun rose, an army unit in a convoy of trucks raced toward the town, entering it with guns ablaze. Above, a helicopter gunship added to the firepower. The “terrorists” were gunned down, left and right (all staged with blank ammunition). The others were rounded up and thrown into extra trucks under heavy guard. In short order, the victorious regular army captain had liberated the town. A loudspeaker in the helicopter called the villagers to return. All was safe! Fires were extinguished. Things returned to near normal.

Meanwhile, the captain remained with his interrogators, questioning the prisoners. Two “insurgent” leaders were discovered with false “terrorist” papers in their pockets and led back to the village square in chains. Charges were read against them, and the villagers observed them backed against the wall and shot! No sooner had the bodies hit the ground than they were picked up and tossed into the nearest truck. Justice had been done.

All trucks moved down the road. The battle was over. Before leaving, the captain turned to the town’s mayor and warned him against further terrorism. The townspeople cheered the heroic captain as he left the town in command of the convoy. The forces of justice had been victorious. They drove on a few more miles, and the whole gang – loyal army and “terrorists” – had breakfast together. The “dead” men joined the feast.

This was the “mock battle.” Although I have added technical details to the Spanish scenario, I have been to such training programs at US military bases where identical tactics are taught to Americans as well as foreigners. It is all the same. As we shall see later, these are the same tactics that were exploited by CIA superagent Edward G. Lansdale and his men in the Philippines and Indochina.

This is an example of the intelligence service’s “Fun and Games.” Actually, it is as old as history; but lately it has been refined, out of necessity, into a major tool of clandestine warfare. Lest anyone think that this is an isolated case, be assured that it was not. Such “mock battles” and “mock attacks on native villages” were staged countless times in Indochina for the benefit of, or the orientation of, visiting dignitaries, such as John McCone when he first visited Vietnam as the Kennedy-appointed director of central intelligence. Such distinguished visitors usually observed the action from a helicopter, at “a safe distance.” A new secretary of defense, such as Robert McNamara, who had never seen combat, especially combat in Southeast Asia, would be given the treatment. It was evident to other, more experienced observers that the tracks through the fields had been made by the ‘Vietcong” during many rehearsals of the “attack.” The war makers of Vietnam vintage left nothing to chance.

During the 1952-54 time period, when I flew in to the Philippines, I spent many hours talking with Ed Lansdale, his many Filipino friends, such as Juan C. “Johnny” Orendain, Col. Napoleon D. Valeriano, and members of his CIA “anti-Quirino” team and heard them tell these same stories. They all worked with Ramon Magsaysay in those days and related how he would divide his Special Forces into the “Communist HUKs” and the loyal military and then attack villages in the manner described above. Before long Ramon Magsaysay had been “elected” president of the Philippines, and President Quirino was on his way out. Later, when I worked in the same office with Lansdale in the Pentagon, he would relate how he and his Saigon Military Mission teammates applied similar tactics in Indochina, both North and South.

Not long after the CIA had been created, limited by law “to coordinate intelligence,” the National Security Council authorized the super-secret Office of Policy Coordination, under the wartime OSS station chief in Romania, Frank Wisner, to carry out certain covert operations of a similar nature. This is the organization Ed Lansdale was assigned to in November 1949. There he worked under an experienced Far East hand, Col. Richard G. Stilwell, in the Far East /Plans division. The clandestine warfare in Greece and Bulgaria, which occurred at about the same time, is another example of OPC’s undercover work. [emphasis added]

During the late forties, the CIA organized itself and grew. In these same years the OPC grew faster, and when Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, General Eisenhower’s chief of staff during WWII, returned from Moscow, where he had been the US ambassador, to become the director of central intelligence, one of his first official acts was to have the OPC removed from the secretary of state and the secretary of defense and to have it placed directly under his control in the CIA. Although there was no lawful basis for this momentous move, it was done without formal protest. Everyone involved knew that the real reason for the creation of the CIA was to be the lead brigade of US. forces during the Cold War period.

Then, with the election of President Eisenhower in 1952, Allen W. Dulles was made the director of central intelligence, General Smith became the deputy secretary of state, and John Foster Dulles was made secretary of state. The high command for the Cold War was in place, and the stage was set for the CIAs dominant role in the invisible war. The Korean War, which had begun in 1950, had served to cover the CIAs rapid expansion into that field.

By 1952 it had been decided that the time had come to replace Quirino as president of the Philippines. Since he was, ostensibly, a good friend of the United States and avowedly an anti-Communist, it would require some delicate diplomacy to bring that about. The reasons for the forced removal of a national leader do not always follow ideological or political lines. It is more likely, as in the case of Quirino, that he had relaxed his business priorities with the United States in favor of other countries, thus reducing American exports to the Philippines. And that could be sufficient grounds for the removal of a leader in the big power game of the nation-states.

While the United States maintained the customary diplomatic relations with the Quirino government and had a strong ambassador in Manila, that ambassador had on his staff a strong CIA station chief, one George Aurell. This cloak of normalcy could not be changed. The ambassador urged Quirino to hold an election. Elections would be good for Quirino and would serve to quell the opposition, said to consist of a Communist-supported HUK rebellion. Other than that, Quirino saw no opposition and no problems with an election. An election was scheduled – for later.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to the ambassador and Aurell, the CIA slipped into the Philippines an undercover team headed by one of its superagents, Edward G. Lansdale. Although the true reason for his presence in Manila was not divulged to these senior Americans, this agent had access to certain anti-Quirino Filipinos. His ostensible role was to train selected Filipino army troops in PsyWar and other paramilitary tactics; his primary role, in fact, was to oust Quirino and to install Ramon Magsaysay in the office of president. The men selected for duty with Lansdale were put on regular training schedules with the US. Army and were trained outside of the Philippines. Then they were slipped back later into the Philippines and into their usual army units.

At the same time, all throughout the islands, the “HUK insurgency” was escalated by secret operations. News began to surface about the growing HUK insurgency. The HUKs were beginning to be found everywhere. There were reports of “HUK detachments” on all the islands. The rise of this notional “Communist” influence gave President Quirino what he thought was a strong platform. The Cold War “make war” tactic was well under way.

Then the CIA made its move. Lansdale had selected a handsome young Philippine congressman, Ramon Magsaysay, to play the role we have seen in the above scenario from Spain. He was to stage “mock attacks” and “mock liberations” on countless villages throughout the islands. Villages were attacked and destroyed by the “HUKs.” Captain Magsaysay and his loyal band charged into town after town, killing and capturing the “HUKs” and liberating each village. This CIA agent had been equipped with the equivalent of a bookfull of blank checks that he used to finance the entire campaign. The CIA pumped out a flood of news releases, produced and projected propaganda movies, and held huge rallies – all to build up the reputation of the new “Robin Hood,” Ramon Magsaysay. The plot was a success, and soon Magsaysay was made secretary of defense. Then, when the election campaign began, he ran for president against Quirino. Quirino was stunned by the entry of the “HUK Killer” hero into the campaign. But the president had one more ace up his sleeve: He had the traditional power to control the ballot boxes and to count the votes. An honest election was quite impossible in the Philippines.

The election was held. Magsaysay was certainly more popular than Quirino. Just prior to the election, the “HUKs” stirred themselves and rekindled Filipinos’ memories of the gallant captain who had liberated their villages with a hot machine gun slung across his arm. The votes for Magsaysay poured in from all the islands. Then, from his office in the army, he sent out a command. He ordered his own loyal army troops to guard every voting site. Anny men sealed and loaded the ballot boxes into trucks and drove them to Manila, where all the votes were counted, in public. As they said on the streets, “Under those conditions a monkey could have won against Quirino.” Quirino was outmaneuvered by this new tactic. Magsaysay won easily and became president of the Philippines.

In Manila, Quirino was not the only man stunned by these events. So was the American ambassador and, even more so, his CIA station chief, George Aurell. They fin ally realized that the CIA had kept them in the dark by concealing the true role of one of its most powerful undercover teams. The CIA had quietly pulled off the deal, right under their noses. Another battle in the Cold War had been won over “the forces of communism” – or so they were led to believe.

Magsaysay had become president as a result of the application, many times over, of the same scenario that those two officers in Spain had used in their mock attack. With Magsaysay president, the city was too small for the US. ambassador, CIA station chief, and CIA secret agent – the Magsaysay creator, with his Madison Avenue-type warfare and election campaign. Also, quite magically, it seemed that the HUKs had vanished. Cecil B. deMille could not have staged it any better.2

These are examples of the new intelligence methods that are actually “make war” tactics. The Spanish incident and the Magsaysay “election campaign” serve to illustrate how they work. The incidents recounted below will serve to broaden the reader’s understanding of the CIA’s worldwide operations. During the late forties, there was trouble in Greece, and the fledgling CIA got a foothold there and began to develop a major empire in that region. Greece became a base for overflight reconnaissance aircraft. Secret airfields were used in Greece and in Turkey; and from the time of the murder of Premier Muhammad Mossadegh of Iran, in 1953, the CIA was the most potent force behind the shaky throne of the Shah of Iran.

…, more than one-half of all the military materiel once stockpiled on Okinawa for the planned invasion of Japan had been reloaded in September 1945 and transshipped to Haiphong, the port of Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital. This stockpile had amounted to what the army called a 145,000 “man-pack” of supplies, that is, enough of everything required during combat to arm and supply that many men for war.

Once in Haiphong Harbor, this enormous shipment of arms was transferred under the direction of Brig. Gen. Philip E. Gallagher, who was supporting the OSS, and his associate, Ho Chi Minh. They had come from China to mop up the remnants of the defeated Japanese army. Hos military commander Col. Vo Nguyen Giap, quickly moved this equipment into hiding for the day when it would be needed. By 1954, that time had come.

On January 29, 1954, a meeting of the President’s Special Committee on Indochina convened in the office of the deputy secretary of defense, Roger M. Kyes. The ostensible purpose was to discuss what could be done to aid the French, who had made some urgent requests for military assistance. A major item on the agenda of this meeting was the reading of the “Erskine Report” on Indochina. Gen. Graves B. Erskine, USMC (Ret’d), was assistant to the secretary of defense, special operations, 1953-61, and under President Eisenhower was chairman of the Working Group of the President’s Special Committee on Indochina3 This important report “was premised on US action short of the contribution of US combat forces.”

At the end of the meeting Allen Dulles, then the director of central intelligence, suggested that an unconventional-warfare officer, Col. Edward G. Lansdale,4 be added to the group of American liaison officers that Gen. Henri Navarre, the French commander, had agreed to accept in Indochina. The committee thought this arrangement would prove to be acceptable and authorized Dulles to put his man in the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), Saigon. [emphasis added]

The start of a new phase of the a SS/CIA activity in Indochina, this step marked the beginning of the CIA’s intervention into the affairs of the government of Indochina, which at that time was French. It was not long before the reins of government were wrested from the French by the Vietminh, after their victory at Dien Bien Phu under the leadership of our friend of OSS days, Ho Chi Minh.

With this action, the CIA established the Saigon Military Mission (SMM) in Vietnam. It was not often in Saigon. It was not military. It was CIA. Its mission was to work with the anti-Vietminh Indochinese and not to work with the French. With this background and these stipulations, this new CIA unit was not going to win the war for the French. As we learned the hard way later, it was not going to win the war for South Vietnam, either, or for the United States. Was it supposed to?

This is the way the CIA’s undercover armies work, as they have operated in countless countries since the end of WWII. They move unobtrusively with a small team, plenty of money, and a boundless supply of equipment as backup. They make contact with the indigenous group they intend to support, regardless of who runs the government. Then they increase the level of activity until a conflict ensues. Because the CIA is not equipped or sufficiently experienced to handle such an operation when combat intensifies to that level, the military generally is called upon for support. At that time the level of military support has risen to such an extent that this action can no longer be termed either covert or truly deniable. At that point, as in Vietnam, operational control is transferred to the military in the best way possible, and the hostilities continue until both sides weary of the cost in men, money, materiel, and noncombatant lives and property. There can be no clear victory in such warfare, as we have learned in Korea and Indochina. These “pseudowars” serve simply to keep the conflict going. As we have said above, that is the objective of these undercover tactics.

This concept of the necessity of conflict takes much from the philosopher Hegel (1770-1831). He believed that each nation emerges as a self-contained moral personality. Thus, might certifies right, and war is a legitimate expression of the dominant power of the moment. It is more than that. It is a force for the good of the state since it discourages internal dissent and corruption and fosters the spiritual cement of patriotism.

And in this excerpt we get to see how our republic used to work. Please notice the players. Again, from Fletcher Prouty’s JFK, The CIA, Vietnam, and the Plot to Assassinate John F. Kennedy:

In late 1960, when the departing President, Dwight Eisenhower, met with his successor, John F. Kennedy, he told him that the biggest trouble spot would be in Laos and that with Ngo Dinh Diem in Saigon, he had little to worry about there. U.S. participation in Laos is another story, but one factor of the fighting in Laos did have a most significant impact upon the escalation of the war in South Vietnam: It began the evolution of an entirely new set of tactical characteristics of that warfare.

A full squadron of U.S. Marine Corps helicopters had been secretly transferred, at the request of the CIA, from Okinawa to Udorn, Thailand, just across the river from Laos. The helicopters that saw combat in Laos were based and maintained in Thailand by U.S. Marines. These military men did not leave Thailand; the helicopters were flown to the combat zones of Laos by CIA mercenary pilots of the CAT Airlines organization, under the operational control of the CIA.

In those days, in accordance with the provisions of National Security Council Directive #5412, every effort had been made to keep U.S. military and other covert assistance at a level that could be “plausibly” disclaimed. The theory was that if these operations were compromised in any way, the U.S. government should be able to “disclaim plausibly” its role in the action. In other words, these helicopters had been “sterilized.” There were no U.S. Marine Corps insignia on them, there were no marine serial numbers, no marine paperwork, no marine pilots. This was at best a thin veneer; but the veneer was needed to make it possible to use the marine equipment.

Back in Saigon, CIA operators wanted those helicopters transferred to Vietnam. Many of the CIA agents who had been infiltrated into South Vietnam, contrary to the provisions of the Geneva Agreements, had been moved there secretly from Laos. While in Laos they had become accustomed to the use and convenience of this large force of combat helicopters. They wanted them in Vietnam, where they proposed to use them to transport South Vietnamese army troops to fight the fast-growing numbers of “enemy” who were rioting for food and water in the rice-growing areas of the Camau Peninsula. This helicopter movement was planned to be the CIAs first operational combat activity of the Vietnam War. It turned out to also be the first step of a decade of escalation of that war.

At that time, all American military aid to South Vietnam was strictly limited by the “one for one” replacement stipulation of the 1954 Geneva Agreements. The CIA could not move a squadron of military helicopters into South Vietnam, because there were no helicopters there to replace. So movement of those helicopters from Laos would have to be a covert operation. Any covert operation could be initiated and maintained only in accordance with a specific directive from the National Security Council and with the cooperation and direct assistance of the Department of Defense.

The CIA’s first attempt to have these helicopters moved for combat purposes came in mid-1960 and was an attempt to beat the system. Gen. Charles P. Cabell, the deputy director of central intelligence, called one of his contacts (who happened to be this author) in the Office of Special Operations (OSO), a division of the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), to see if these helicopters could be moved to Vietnam quickly and quietly, on an emergency basis, because of the outbreak of rioting all over the country.

In those days, the Office of Special Operations followed the policy set forth by Secretary of Defense Thomas Gates, which closely followed the language of the law, that is, the National Security Act of 1947. The pertinent language of that act states that the CIA operates “under the directions of the NSC.”

At the time of General Cabell’s call, OSO had received no authorization for such a move, and the request was denied on the ground that such a move would be covert and that the NSC had not directed such an operation into Vietnam. During the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations, the letter of this law was followed carefully.

In most cases, the CIA did not possess enough assets in facilities, people, and materiel to carry out the operations it wanted to perform. Therefore, the CIA had to come to the military establishment for support of its clandestine operations. The Defense Department would not provide this support without an agreed-upon NSC directive for each operation and usually without a guarantee of financial reimbursement from the CIA for at least “out-of-pocket” costs. This kept the CIA at bay and under reasonable control during these more “normal” years.

There is an interesting anecdote from this period that reveals President Eisenhower’s personal concern with clandestine operations. Control of the CIA has never been easy. During the early part of Eisenhower’s first term, the NSC approved a directive – NSC 10/2 – that governed the policy for the development and operation of clandestine activity. The NSC did not want covert operations to be the responsibility of the military. It said, quite properly, that the military’s role was a wartime, not a peacetime, one. Therefore, such operations, when directed, would be assigned to the CIA. At the same time, it had long been realized that the CIA did not have adequate resources to carry out such operations by itself and that it was better that it didn’t.

Thus, the NSC ruled that when such operations had been directed, the CIA would turn to the Defense Department, and when necessary, to other departments or agencies of the government, for support.

Sometimes the support provided was considerable. President Eisenhower was quite disturbed by this policy. He saw that it would create, within the organization of the CIA, a surrogate military organization designed to carryout military-type covert operations in peacetime. It would follow, he thought, that the CIA might, over the years, become a very large, uncontrollable military force in itself. He could not condone that, and he acted to curb such a trend.

President Eisenhower had written in the margin of the first page of the NSC 10/2 directive, on the copy that had been sent to the Defense Department: “At no time will the CIA be provided with more equipment, etc., than is absolutely necessary for the support of the operation directed and such support provided will always be limited to the requirements of that single operation.”

This stipulation by the President worked rather well as long as the Office of the Secretary of Defense enforced it strictly. Later, certain elements of the military turned this directive around and began to use the CIA as a vehicle for doing things they wanted to do- as with the Special Forces of the U.S. Army, but could not do, because of policy, during peacetime.

This situation was confronted seriously by President Kennedy immediately following the failure of the Bay of Pigs operation in April 1961.3

By the early 1950s, former President Harry S. Truman was saying that when he signed the CIA legislation into law, he made the biggest mistake of his presidency. In those same years, President Eisenhower had similar thoughts, and he did everything he could to place reasonable controls on the agency. Both of these men feared the CIA because of its power to operate in secrecy and without proper accountability.

During the Eisenhower administration, the Defense Department was usually scrupulous about this note penned on NSC 10/2 by the President and was careful to limit support to that needed for the current operation. The result was that there was always close cooperation and collaboration between the agency and the Defense Department on most clandestine operations. In other words, the clandestine operations carried out during that period were usually what might be called joint operations, with the CIA being given operational control. This applied to the development of all “military” activities in Vietnam, at least until the marines landed there in March 1965.

This NSC policy applied to that request for helicopters from General Cabell of the CIA and accounts for the fact that his original request was vetoed by the Defense Department. This veto required the CIA to prepare its case more formally and to go first to the NSC with its request for the helicopters. In those days, the NSC had a subcommittee, the “5412/2 Committee,” or “Special Group,” that handled covert activities. This group consisted of the deputy undersecretary of state, the deputy secretary of defense, the President’s special assistant for national security affairs, and the director of central intelligence, the latter serving as the group’s “action officer.” In 1957, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff also became a member. Approval for these helicopters was eventually obtained from this Special Group, and the secretary of defense authorized the Office of Special Operations to make all arrangements necessary with the Marine Corps to move the aircraft to Vietnam – secretly – from Udorn, Thailand, to an area south of Saigon near Camau.4

Perhaps more than any other single action of that period, this movement of a large combat-ready force in 1960 marked the beginning of the true military escalation of the war in Vietnam. From that time on, each new action under CIA operational control moved America one step closer to intervention with U.S. military units under U.S. military commanders.

By 1960-61, the CIA had become a surrogate U.S. military force, complete with the authority to develop and wage warfare during peacetime.5

In the process, the CIA was fleshed out with U.S. military personnel who had been “sheep-dipped”6 to make it appear that only civilians were involved. This process was to have a detrimental impact upon the implementation of the Vietnam War: It put CIA civilian officials in actual command of all operational forces in the fast-growing conflict, at least until 1965. As an additional factor, the concealment of military personnel in the CIA led to many of the problems that the armed forces would later delegate to the League of Families of Prisoners of War in Southeast Asia.

By the time this policy giving the CIA “operational” control over all American pseudomilitary units in Vietnam was changed, the “strategy” of warfare in Southeast Asia had become so stereotyped that such true military commanders as Generals Westmoreland and Abrams found little room to maneuver. They were required to take over a “no-win,” impossible situation without a military objective, except that of the overriding Grand Strategy of the Cold War: that is, to make war wherever possible, to keep it going, to avoid the use of H-bombs, and to remember Malthus’s and Darwin’s lessons that the fittest will survive.

Therefore, when the NSC directed a move of helicopters to Vietnam, it ordered the Marine Corps unit at Udorn to be returned, with its own helicopters, to Okinawa. New helicopters of the same type were transported from the United States – meaning, of course, that new procurement orders of considerable value were placed with the helicopter-manufacturing industry, a business that was almost bankrupt at the time.

At the same time, the CIA had to put together a large civilian helicopter unit, much larger than the original Marine Corps unit, with maintenance and flight crews who were for the most part former military personnel who had left the service to take a job at higher pay and a guarantee of direct return to their parent service without loss of seniority. This meant that overseas, combat wage scales were paid to everyone in the unit, at a cost many times that of the military unit it replaced.

As soon as the helicopters arrived and were made ready for operational activities, the CIA’s “army” began training with elite troops of the new South Vietnamese army. They were being hurried into service against those villages where the most serious “refugee-induced” rioting was under way. This operation opened an entirely new chapter of the thirty years of war in Vietnam.

Now who was the enemy? When CIA helicopters, loaded with heavily armed Vietnamese soldiers, were dispatched against “targets” in South Vietnam, who could they identify as “enemy”? It was during this period that we heard the oft-repeated reply “Anyone who runs away when we come must be the enemy.”

… in December 1960, President-elect Kennedy made a surprising announcement. He had decided to keep Allen W. Dulles as his director of central intelligence and J. Edgar Hoover as head of the FBI. With this announcement, the stage was set for the 1960s – the decade in which hundreds of thousands of American fighting men would see action in the escalating war in Vietnam.

to be continued…

Watergate Exposed: How the President of the United States and the Watergate Burglars Were Set Up (as told to Douglas Caddy, original attorney for the Watergate Seven), by Robert Merritt is available at TrineDay, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, The Book Depository, and Books-a-Million.