The Dark Arts of Empire: Part Two

By: Douglas Valentine

(Originally published on CounterPunch)

In the nearly fifty years since the Vietnam War ended, Vietnam has evolved from ecological and economic devastation into a must stop for American tourists. Ukraine recently approached Vietnam as a mediator in its “dispute” with Russia.[1] America, meanwhile, continues to suffer from the Vietnam Syndrome, as discussed in my book Pisces Moon: The Dark Arts of Empire from which the following chapters are excerpted. The book is written as a daily journal. As autobiography, it reveals why investigating the CIA was both a social quest to understand the dark side of the American psyche, and a personal quest to better understand myself and where I fit within my country. I embarked, fittingly, as the sun was about to enter Pisces, the astrological sign ruling deception, espionage, foreign things, prisons and religion. (Part One can be read here.)

Robby in the Lobby: Wednesday, 27 February 1991

“Straighten out your affairs. Slow down your pace. Stop worrying about things you cannot change. Prepare for the full Moon.”

In the summer of 1992, a team of British zoologists traveled to the Vu Quang Nature Reserve in Central Vietnam to search for the elusive “forest goat,” otherwise known as the “Asian unicorn.” They weren’t even sure it was a goat. It might have been a miniature ox, or a tiny water buffalo, or an antelope. As of 1992, no Western zoologist had ever seen one and thus they did not officially exist. That any creatures still existed in the region was in itself remarkable, given the millions of bombs the US military dropped on it and in neighboring Cambodia and Laos during the war.

As proof of existence, the zoologists had two long, slender antlers the unicorns used to fend off tigers and other predators. The antlers were obtained through Vietnamese scientists in contact with members of the Bru people living in the nature reserve. The Bru were familiar with the forest goat and for generations had ground its horn into powder for use as an aphrodisiac. Like many indigenous tribes throughout Southeast Asia, the Bru hunted with crossbows and blowguns, cannibalized their enemies and practiced sorcery.

As I’m sure the Bru would agree, the effects of a full moon are inescapable. And this particular full moon would peak at nine degrees in the sign of Virgo – exactly where the moon had been when I was born – activating the Pisces-Virgo axis that existed at the moment of my birth. Helen described it as “the most delicate axis in the Zodiac: Virgo is the awareness and settling of your karmic affairs: Pisces is their inevitable dissolution into the whole. But the prevailing instinct now is to maintain individual integrity at all costs.”

Settling my affairs meant smoothing things over with the Vietnamese authorities and getting to Thailand for my interviews. The authorities had done nothing to lead me to believe I was in trouble. I’d registered the car before I left and the Tay Ninh cops had treated me well. I believed they were flexible and forgiving. Unlike BBC. I didn’t trust BBC to tell the truth about anything. To appease the CIA, they’d isolated me without any translation services or support of any kind. It was a mean-spirited set-up and I was not about to follow their edict to stay in the hotel.

I slept a few hours and felt somewhat refreshed, and after breakfast I walked over to the Vietnam Air office to confirm my flight. And there I discovered that all was not well. The English-speaking clerk told me, in a perfunctory and unpleasant manner, that my name was not on the manifest. My flight out of Vietnam had not been confirmed. I couldn’t leave.

The Caravelle Hotel was a few blocks away, so I walked over to see Julie. I rang her room at the front desk and she said she’d be right down. While waiting, I asked if Lillian Morton was there. She was not. Lillian had gone north to Hanoi on the second leg of her journey.

Julie appeared moments later and we sat in the lobby amid a group of lounging Vietnamese. Their stares made her squirm in her seat. She asked if I was feeling better. I said I was adapting and asked how she was doing. “I can’t wait to go home,” she replied. At the thought of home, a tear glistened in the corner of one eye. She was haggard, fidgeting, a nervous wreck. I felt sorry for her. “I’ve been here nearly a month,” she added emotionally.

Stiffening her upper lip, Julie got down to business. She said the Vietnamese were upset and that I must stay in my hotel room until Mrs. Huong from the Ministry of Culture, Information, Sports and Tourism contacted me. She said I was under house arrest and that my departure from Vietnam had been indefinitely postponed until my status was resolved. She asked, disapprovingly, if I’d gotten her note telling me to stay in my room.

I said I had but that it hadn’t mentioned anything about my being under house arrest – let alone confined to my room. “As you know,” I said, “I’m required to confirm my flight and it wasn’t until I got to Vietnam Air that I learned it’s been delayed.”

During our chat Julie had become so disconcerted by the unabashed staring and listening of the Vietnamese around us that she stood and said rather brusquely that she had some pressing chores to do for Molloy. She asked if we could continue our chat over lunch at the Majestic. I agreed and returned to my hotel. I’d been in my room for two minutes when the phone rang. It was Mrs. Huong from the Ministry of Culture. “Mr. Valentine,” she said frantically, “I’ve been trying to reach you for days!”

“Hello, Mrs. Huong,” I replied. “How are you?”

“I’m fine, Mr. Valentine,” she said, nonplused. “How are you?”

“I’m okay, thanks. But I’m concerned. I was just at the Vietnam Air office and they said my flight to Bangkok tomorrow was indefinitely postponed. I have important business in Thailand. I hope we can straighten things out quickly.”

“Mr. Valentine!” she exclaimed, peeved by my insouciance. She let my name hang in the air while she composed herself. “Mr. Valentine,’ she repeated angrily. “You must explain what you’ve been doing before you can leave Vietnam. We cannot have tourists traveling around the countryside without permission. Everyone must follow the rules.” I didn’t respond, so she continued. “We’re sending someone to your hotel to speak to you. He’ll be there at six-thirty this evening. You must stay in your hotel until he arrives and this matter is straightened out. Do you understand?’

I understood.

“Good. You are in serious trouble, Mr. Valentine. I hope you will comply with our wishes.”

“Of course, Mrs. Huong,” I said. “But you’ll find that the problem is not of my making.”

“We’ll see, Mr. Valentine. Goodbye.”

***

I walked onto the balcony and contemplated what it meant to be under house arrest in a country that didn’t have diplomatic relations with mine. Not that any US official would ever help me, but there was nowhere to go for help. Not a soul in my address book I could call for help, either. More distressing was the prospect of a missed opportunity of a lifetime. Saigon was spread out before me and beyond was Thailand, waiting to be explored. But I was trapped and the feeling led to a moment of panic, like I was in a car skidding out-of-control on black ice, hurtling headlong at on-coming traffic. The next few moments were filled with crushing loneliness and apprehension so profound I literally had an out of body experience. I felt my consciousness leave my body, as if it were trying to travel back home on the astral plane. I pulled myself together, focused on the street scene, spied the cyclo driver with the baseball cap. He was smiling and looking up at me from the corner. He waved merrily. In The Quiet American, a cyclo driver in Fowler’s employ signals Pyle’s doom. Synchronicity?

I chuckled and realized I was being melodramatic. I wasn’t facing time behind bars. They might chew me out but no one was going to break my arm. “Stop worrying about things you cannot change,” Helen had advised. Which is what a writer does when he can’t get involved. He records. So I wrote about everything that had happened and then I did some tai chi.

At 12:45 the desk clerk called to say Julie was downstairs. I’d run out of Lomotil and Septra and had flushed my malaria pills down the toilet. The health crisis had passed but I needed a joint.

I met Julie in the lobby and asked where she’d like to sit. She chose a table as far from the veranda as possible. She was cocooning and didn’t want to see the street. It was all she could do not to gripe about the heat and the heathens. I asked what she wanted for lunch. She blanched at the mention of food and ordered a chicken sandwich. When it arrived, she was horrified to find that it was not the white meat and mayonnaise kind of sandwich she had envisioned. The meat was dark and stringy and came on the bone. “Some people say it’s pigeon,” I cruelly observed. She gagged.

While we talked, Julie used her fork to pull short strips of stringy meat off the bone. She manically segregated the meat on a corner of her plate and nibbled the dry parts of bread that hadn’t touched it. A part of me sympathized, but I couldn’t tolerate her contempt for the Vietnamese. And for me. She looked down her long thin nose at me like a sniper aligning the Patridge sights on a rifle.

We made small talk. I asked if BBC was accomplishing what it had set out to do. Had they gotten into the National Interrogation Center in Saigon or any province interrogation centers?

Julie said things had gone “as well as could be expected in Vietnam.” BBC had done a lot of filming in Long An Province. They’d shot scenes of village life and yes, they’d gotten into the province interrogation center, which was “shabby, like everything else in Vietnam.” The film crew had asked to get into the National Interrogation Center but it was being used and was off limits.

I mentioned that I’d been to the Cao Dai Temple, and she said that BBC had filmed a service there. They’d also been to Vung Tau, southeast of Saigon on the coast. Vung Tau was where the CIA had trained its counter-terror and political action cadres.

Filming at the Cao Dai Temple, Vung Tau and an interrogation center were things I’d suggested they do. Giving me credit, however, was not in BBC’s script. Sensing that she had told me too much, she turned the conversation back to my situation. “Doug,” she said with a sniff, “You do know that you’re being detained and that you’ll have to stay in the hotel today? I believe Mrs. Huong is sending someone to speak to you tonight. Isn’t that right?”

“That’s right,” I acknowledged.

“If all goes well, you’ll only be detained for one day. You’ll be leaving on Friday instead of Thursday. Incidentally, Friday is Orderly Departure Program Day, the day each week when refugees are allowed to leave Vietnam. ODP Day gets to be something of a madhouse, but if you follow instructions, it should all go well. In any event, as soon as the people from the Ministry give us the green light, we’ll straighten out your hotel bill and then you can go. Okay?”

“Great,” I said agreeably. That was encouraging news, though between the lines she was hinting that BBC would not pay my hotel bill unless I toed the line. Which was okay. I was not about to make a fuss. I asked if she would contact the Mandarin in Bangkok and change my hotel reservation. She said I should call myself, that BBC would be paying my phone bill as well.

“Thanks,” I said dubiously.

“You know, Doug,” Julie said indignantly, “people in your predicament have been detained for up to a month! The people from the Ministry held one of our film crews in some wretched village for a week, simply because one of our people didn’t have the proper clearances.”

Should have had a few Benjamins, I thought, but didn’t say it. Julie had raised the subject of my arrest, however, so I asked what had happened “at their end” that fateful day. Peter, she said, had gotten furious about my “escapade.” The ministry people had contacted BBC on Tuesday morning about my paperwork, prompting Julie to send the first note. Later that day, while BBC was on location in Long An, the police appeared on the set and suspended filming while they sorted out my status. During that time, several phone calls had gone back and forth from Tay Ninh to Saigon and the film crew had to sit around and watch the precious daylight fade.

There was more, of course, to the story. Julie did not mention the ten grand I had carried or that Molloy had denied that I worked for BBC. But I’d already decided not to press the issue. Instead, I politely asked if she had read my first book?

“No,’ she replied. She seemed interested. “What’s it about?”

I told her my father had been a POW in the Philippines, the only American in a camp with 120 Australians and 44 Brits. The camp commander was an English major who, on Christmas Eve, 1943, informed on four Australians who had escaped that night. The Japanese re-captured the Aussies and beheaded them on Christmas morning. That same night the Aussies held a war council, drew straws and sent three men, including my father, to murder the major.

I believe Julie was a good person doing her boss’s bidding. Frightening her was not something I enjoyed. But I wanted to let Molloy know I had horns too.

Julie got the point. Knowing I was unrepentant and angry, she abruptly left, dabbing at her lips with her napkin, warning me not to walk alone in the park at night.

***

Thuan our driver at Giau’s house.

Thuan our driver at Giau’s house.

After Julie left, I walked over to the cubby hole bar by the veranda and ordered a Grand Marnier. I peered over the topiary on the veranda onto Bach Dang at the parade of motorbikes and cyclos, conical hats and black pajamas. Across the sun-drenched park, assorted barges and boats plowed up and down the Saigon River, flying the red Vietnamese flag with its single yellow star. To accompany my second soothing brandy, I asked the black jacketed bartender for a cup of coffee. He poured the lukewarm, syrupy liquid from a thermos.

I was alone and feeling as blue as can be when from out of nowhere a pack of Parliament Lights landed on the bar beside me. I was overcome with nostalgia. Parliament Lights were my brand. I looked at the pack lying there invitingly and I wondered – could it be that an American was standing beside me?

I heard the man order a beer in English. I couldn’t believe it. Nothing in my horoscope had foretold this. Loneliness and the desire for an American cigarette compelled me to turn and ask, “Can I bum one of your smokes?”

“Sure,” he replied, causally shaking one out of the pack. He gave me a light with a steady hand.

Feeling awkward and wanting to return the favor, I asked if I could pay for his beer.

“Oh, no,” he said, “that’s not necessary.”

“Please. It’d make me feel better. It’s really only fair.”

“Well in that case, sure,” he smiled. “Take as many as you want. I got a carton back in my room.”

“You came prepared,” I observed. “Where’re you staying?”

“Two blocks up at the Bong Seng. There’s much more going on in Vietnam this time than the last time I was here. So much more business this time, I couldn’t get a room at Cuu Long or Saigon Mini. A good friend of mine lives at the Mini. How about you? Where are you staying?”

“Right here,” I said, introducing myself. We shook hands and he introduced himself as Robby from upstate New York. He was medium built with short brown hair, shaggy mustache, soft brown eyes, casually dressed in blue jeans and a pale blue, short sleeved shirt. Everything about him put me at ease. I asked him what he did for a living.

Robby was an engineer for a company out of Chicago. The company had a contract with the US government inspecting hydraulic systems on military aircraft. Robby had learned his trade as a technician on fast attack submarines in the navy. He’d gone to work for this company right after leaving the navy in 1979. He’d worked all over the world since then doing instrumentation and calibration. “Avionics,” he called it.

His story got interesting. He’d been working in Kuwait when Iraq invaded. Curious to know what that experience was like, I offered to buy another round. Robby had nothing to do that afternoon, so we took our drinks to a table in the shade on the veranda where he described how he and a co-worker had driven a company jeep out of Kuwait mere hours ahead of the encroaching Iraqi tanks.

The day was bright and hot as we watched the boats on the river. It was dreamy, sitting on the veranda sipping drinks and listening to the tring-a-linging of cyclos and the sweet voices of kids peering over the hedges trying to sell us chewing gum. Robby described how he and his colleague drove across the desert on a dusty “half-assed” road jammed with traffic and refugees most of whom were “Pakistanis carrying bundles tied with string.” At the end of the road was a crowded Saudi army outpost where he and his buddy were processed and given three-day visas.

I asked if he knew how the war was progressing. He said that Saddam was trying to withdraw his troops, but US warplanes were mercilessly bombing the retreating columns. The Americans, he said, had already taken about 30,000 prisoners.

I asked him why he thought Bush was reacting so violently.

“Money,” he said without hesitation. “No one stepped into Cambodia to stop the Khmer Rouge, because no one had any financial interests there to protect. But Bush’s family and friends have heavy financial interests in Kuwait. Oil interests. Protecting those interests is the military’s top priority. For ten years they’ve been preparing for a fight, building underground complexes, stocking them with supplies, waiting for the day when they could establish a permanent military presence in Iraq. That’s why they sold Saddam so many guns. And that’s why they told him it was okay to invade Kuwait when he found out it was slant drilling into Iraq. It was a provocation, something to get Saddam to overreact.”

“Like the ‘provoked response’ in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1964,” I said.

“Same thing but more sophisticated.”

“Why are you in Vietnam?” I asked.

He laughed. “I can’t go back to Kuwait until they’ve cleaned up the mess. Meanwhile I get to fly anywhere I want for free. Been to Thailand sixteen times. That’s the place I really like. I’m going there for a few weeks to do the raft and elephant thing, spend some time in Bangkok. Then to the Philippines. Thought I’d stop here for a few days along the way. It’s my second time. The first time, last year, I couldn’t get out of Saigon. This time around I want to check out the beach at Vung Tau, the tunnels of Chu Chi, get up to Hue. I’m going to try to get into Laos too.”

I asked if he always traveled alone and he said, “Yeah.” When I asked him why, he said without hesitation, “Total independence.”

“What about getting lonely?”

“Getting lonely is the price you pay for independence. If you get lonely, do something.”

That was great advice. Robby was articulate and forthright, so I asked him, “How does your family feel about your traveling around the world alone?”

“I’m thirty-eight,” he said. “Been married since just after high school. Got a couple of kids. I’m making more money than I ever imagined and that keeps my wife happy. She likes taking care of the house, living in town near her family, having security. I always wanted to travel; you know, ‘See the world.’ I’m restless as hell, can’t help it,” he said with a self-deprecating laugh. “Get cranky if I sit at home. So my wife doesn’t mind. We’ve been married twenty years. It works.

“What about you?” he asked. “What brings you to Saigon?”

I told him I’d written a book about the Phoenix program and was working for BBC as a consultant for a series they were doing on the CIA in Vietnam. I told him about The Hotel Tacloban too.

“Oh, yeah,” he said. “I had an uncle who was a POW in Korea. He’d really like to read that book.”

We agreed that I’d send him a copy when I got home. Then we sat in comfortable silence for a while, sipping our drinks, watching the boats on the river. I mentioned that I was going to Thailand and he recommended places to visit in Bangkok – the Golden Buddha, the Floating Market, the Reclining Buddha – as well as bars catering to Americans in Bangkok’s red-light districts on Patpong Road and Soi Cowboy. He also recommended hotels that specialized in servicing sex tourists and gave me the name of a reliable female escort. Evidently, sex was another reason Robby traveled abroad.

Robby said he was meeting an Australian friend named Chapman for dinner and graciously invited me along. I explained that I was under house arrest and due to meet a person from the Ministry at 6:30. “That’s the sort of thing that happens in Vietnam all the time,” he sighed. Concerned about my well-being, he made me promise to call him later that evening. We agreed that if things worked out we’d spend time together on Thursday. Then he went off to meet Chapman and I went up to my room to prepare to meet the ministry man. I washed, put on a tie, grappled with my apprehensions. At 8:00, the desk clerk rang to say that a man was waiting for me in the lobby.

+++

The ministry man was a tough looking character, dark and tall. He did not speak English and our stilted conversation was conducted through the desk clerk, a nervous middle-aged woman. There was no need for her to be intimidated. Despite his imposing presence, the ministry man was relaxed and low-key. He said the Ministry was sending a van to pick me up at 9:00 am tomorrow for a meeting at its offices on the other side of town. He kindly asked if I had any concerns. When I asked permission to eat at Jackie’s, a nearby Chinese restaurant that Robby had recommended, he said with a big grin that I was free to do what I wanted as long as I didn’t leave Saigon.

So much for house arrest. Nevertheless, my meeting with the ministry man had a visible impact on the hotel staff, with the faint of heart taking a few steps back as I passed, while the adventurous sought to get me alone and tell their war stories.

I was hungry as hell and walked alone through the park to Jackie’s, across from the floating hotel not far from the Saigon Mini where Chapman was staying. It was a decent meal – fluffy rice, white chicken meat, a cold beer that settled my stomach and made me feel optimistic. There was no rest for a weary American in Saigon in 1991, however, and on the way out the door I was buttonholed by a middle-aged waiter. A former officer in South Vietnam’s air force, he’d been recruited by the CIA and was wondering why he’d been left behind by those he’d served so loyally. He said he once had responsibility, respect and power, but now had nothing. Desperate for answers and escape, he asked me why none of his former sponsors would help him get into the US.

I asked him for the names of the people he’d worked for, but he wouldn’t say. I told him without knowing who his bosses were, I couldn’t possibly help. Dejected, he went back inside.

I walked to the Majestic alone through the park, thinking how ironic it was that the same CIA officers who had raped Saigon twenty years earlier were now holed up with their BBC cohorts re-writing history – telling, like Morley Safer had, how some mythical Vietnamese ally had “died for democracy” while the real thing, like the air force major who had believed their promises and done their dirty deeds, waited tables or sold postcards and wondered where their saviors were.

I bought a few bottles of beer at the hotel bar and walked up to the forbidden top floor to honor the full moon. I stood amid the charred remains of what had once been a disco lounge, pulled a padded chair over to the balcony and gazed at the silvery reflection of the moon in the Saigon River, the floating hotel, a Konica sign in the park, the shadowy past, at me.

According to Helen, my Virgo Moon makes me selective in expressing my feelings. “This self-censoring quality prevents you from becoming an emotional wreck and helps you effect your need to be useful. You know where you begin and others end.”

Maybe so. I was going to find out soon enough.

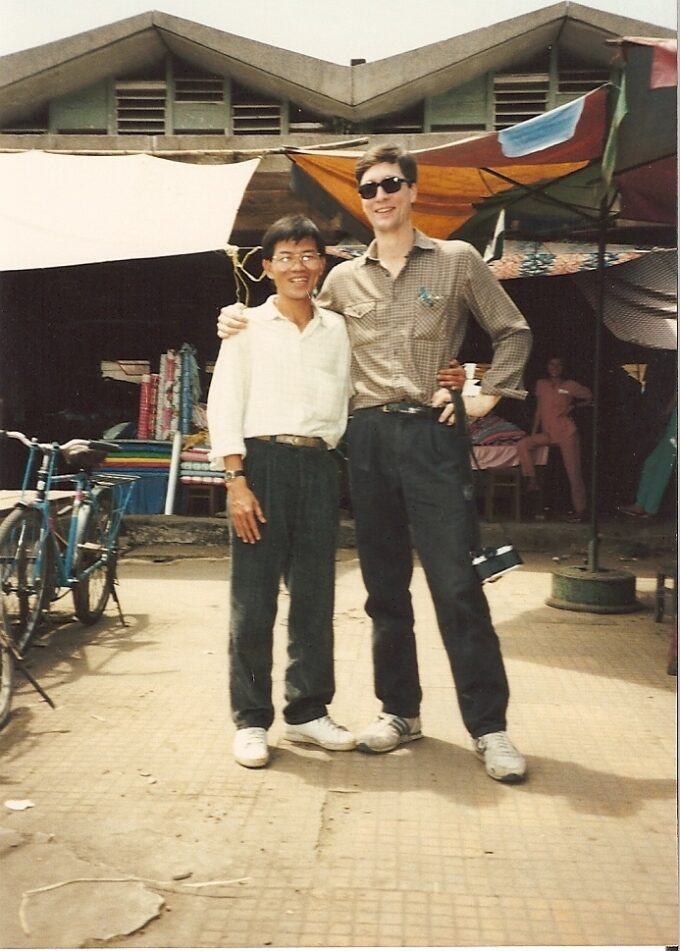

Vinh and the author in Tay Ninh.

Vinh and the author in Tay Ninh.

Madre Cadre: Thursday, 28 February 1991

“Full Moon. Strive for simplicity.”

I was in a bark canoe on Nauro Creek in New Guinea. Standing aft like a gondolier was a Papuan with a long wooden paddle and an ivory bone stuck horizontally through his wide flared nostrils. His curly hair was a black halo. A machete dangled from his loin cloth. Sitting behind me was Bill Shakespeare dressed like the joker in a deck of cards with red pointed shoes, a blue hat with bells, and a ruffled collar. Bill was writing love sonnets. Someone sat in front of me holding the sides of the canoe for balance. His back was a maze of runic tattoos. Birds squawked and huge iridescent butterflies swooped at us from the shoreline as the canoe hurtled past jutting boulders and under moss laden tree branches dripping with deadly green and red snakes. We skated the churning white rapids toward a waterfall and just as we were about to shoot over, the tattooed man turned and I woke up sweating, distraught, tangled in the sheets, trying to forget what I saw.

Morning in Saigon. Sitting and spinning on Saturn’s rings. Settling down, trying to remember when and where, what and why. In a few hours, the people from the Ministry would arrive to collect me. A moment of choking angst. Give us this day our daily dread.

I decided to go to the park to stretch. No point hiding in my room, twiddling my thumbs. Might as well get my blood pumping among the tai chi and badminton players. The few minutes I spent there, however, made me feel like a freakish intruder. Everyone stared with eyes like icicles.

Back at the hotel, I stopped to see if there’d been any messages while I was out. The desk clerk, Cuc, said “No messages,” and gave me a quizzical look. The hotel staff knew I was under house arrest. No one wanted to get in trouble by associating with me, but curiosity got the better of Cuc. She asked what I was doing in Vietnam. I told her.

“You’re a writer, not a journalist?” she said. “So why do you work for BBC?”

I shrugged. Cuc said she’d been a journalist for a Japanese newspaper for seven years before “the Liberation.” She sighed. Times were hard and like many people, she longed for the occupation.

It occurred to me that if BBC were, indeed, paying my bill, the staff would know. I asked Cuc if BBC had arranged to pay my bill. They hadn’t. Trouble was brewing.

Back in my room I placed a call to Robby and we agreed to meet upon my return from the Ministry. Four people from the Ministry of Culture arrived at 9:00 am in a van. We drove to the International Service Centre at 58 Quan Su Street. It reminded me of a ride I had in a paddy wagon in January 1973 in San Francisco. The four people were Messrs. Dung, Trien and Dang, plus my designated contact, Mrs. Huong. Madre Cadre. We sat in chairs and sofas in the corner of a vast empty room on an upper floor wrapped in windows, with a panoramic view of Saigon. Tea was served. Everyone was casually dressed but edgy. Mrs. Huong led the discussion. They had called Saigon Tourist to check my story and were satisfied. The issue was my relationship with BBC. She asked me to explain.

I told her that Molloy knew that I’d written a book on the Phoenix program and that in order to get access to my sources in the CIA, he hired me as a consultant for the BBC documentary. I handed Mrs. Huong The Phoenix Programdust jacket, which I’d brought along just in case. She passed it around. I had everyone’s undivided attention.

Molloy came to my house, I said, and while he was there, I told him how the CIA was organized and operated in South Vietnam. After he left, he contacted all of my CIA sources, some of whom were principals in the documentary. In exchange I was to receive credit and an all-expenses paid, round trip to Vietnam. I produced a copy of the contract, which I’d also brought along just in case. They made a copy.

Their jaws dropped when I added that I’d carried ten-thousand cash, for which I never even received a “thank you” from Molloy. Despite all my good faith efforts, I said, BBC isolated me at the insistence of its contingent of CIA officers. They treated me like a leper and despite our agreement, denied me the rare chance to participate in the filming of the documentary. I’d asked for a driver and interpreter but was denied that too. When I told them I was going to Thanh Ta and Tay Ninh, they made no effort to dissuade me. They merely asked if I had any names of people for them to contact. When I read the list of revolutionaries and progressives, Molloy had recoiled in horror, I said. He was only interested in spewing the right-wing revisionist story.

As further proof of its bad faith, I recalled how BBC had told the Tay Ninh police that I had no business with them. Then I showed them the letter Julie sent me saying BBC would pay for my accommodations. I mentioned that I still had not gotten my plane ticket and was concerned they were not going to pay the hotel bill, either. Then I expressed my belief that former CIA officers Tom Polgar, Frank Snepp and Orrin DeForest, who were consultants to BBC and currently in Saigon, were war criminals determined to revise history under the guidance of reactionary screenwriter John Ranelagh, in order to protect themselves and their CIA sponsors. The CIA hated me for writing the Phoenix book, I said, and in my opinion, BBC had served the CIA by putting me in a separate hotel and cutting me off. They set me up, I said, and in my humble opinion, they were setting up the Vietnamese, too. I rested my case.

“We knew nothing about any of this,” said incredulous Mrs. Huong. Then, holding the Phoenix dust jacket, she asked, “How could you write book about the war without having been here?”

It was a good question. “I did a lot of interviews,” I meekly replied.

+++

Mrs. Huong said I could relax. It was like we were best friends. She gave me her business card and said Desert Storm had ended and the US now occupied Kuwait City. Then the happy gang drove me back to the Majestic. All was well. There was a note from Julie saying my plane ticket had been arranged and that I should call the Mandarin in Bangkok to tell them I was coming. Then she asked me to meet her at the Caravelle at 4:30. I agreed, hoping she would settle my hotel bill then.

I called Robby and we agreed to meet for lunch. It was fun. We took a walk, saw some sights, had a few drinks and a leisurely chat atop the Rex Hotel. Then he asked if I would like to visit a man he knew in the Cholon underground. It didn’t occur to me that someone who had only been to Saigon once would have a contact in the Cholon underground, but I agreed. It was 4:00, however, and first I had to see Julie.

Walking up Dong Khoi, I felt a little like Fowler hoping the police would not revoke his “order of circulation.” I was tired when I met Julie in the Caravelle’s gaudy lounge. A guy was listening, of course, and Julie was cold. Molloy, she said, was terribly upset. After speaking to me, the ministry people had read him the riot act. He wanted to meet for dinner at 7:00 to discuss the situation.

Julie had affected her constipated smirk and she nearly fainted when I politely told her to tell Molloy, “No, thanks.” That I was going to dinner with friends.

Fifteen minutes later I met Robby at the Saigon Mini for a cyclo ride to Cholon to meet his friend Lac Long. It was the only time I actually felt in danger while in Vietnam. Guilty too, riding like a pasha with a coolie working his ass off to move me around. The streets were level, and that helped, but lined with sullen people. We passed a little girl lying under a shroud on the sidewalk. I thought she might be dead. The streets got narrower and more congested the deeper we got into Cholon. The cyclo driver weaved in between people staring hard at me.

Robby showed no concern. He was not embarrassed about being an American. “Don’t make eye contact,” he said. The cyclo drivers parked and vanished as we peered in the window of Lac Long’s curio shop. His sons were there but he was at home. One son went to get him. Robby, apparently, was important. While we waited, people appeared and disappeared inside the shop as if from the woodwork. Robby stood casually, his elbow resting on top of a cabinet of curiosities: rocks and minerals, Buddhas and dolls, carved animals, good luck charms. Everyone wants good luck. The ones who have it are favored by the gods.

Lac Long looked at me angrily when he arrived and said he could only stay a minute. Robby shrugged it off. Then Lac Long gave a short lesson on the realities of why people were forced to create the underground economy that existed in Vietnam. He said, “Being at war changed the meaning of freedom.”

I’ll paraphrase the rest. The US-backed government forced people from their ancestral homes into cities, where boys became drug dealers and tens of thousands of girls became sex slaves to American men so their families could survive. If Morley Safer were honest, he would have said, “They sucked dick for democracy.”

Thank you for your service, girls.

Then Nixon and Kissinger sold out South Vietnam to gain China as a trading partner. But the revolutionaries understood what sanctions meant and allowed the underground to thrive; and BBC to make its documentary; and me to bring in ten-grand in cash. The brutal truth is that everyone has to move on.

+++

I was in a sober mood when we met Robby’s friend Keith Chapman back at the Saigon Mini. An Australian agriculturalist with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Keith was a stocky man with a beard and brown eyes. He knew everyone. When we got back to the Majestic and took a table outside, two cute little girls hopped over the hedge to talk to him. Keith was knowledgeable as well as popular. He said the rural Vietnamese still flocked to Saigon but would be better off in the countryside where food was plentiful. He also said not to worry, that they would survive and prosper. Unlike us, they had plenty of fuel and food and didn’t need imports. The problem, he said, was the environmental disaster the Americans had visited upon Vietnam, thus giving me the authoritative information I needed about Agent Orange poisoning for Fred Dick. Keith compared it to what was happening in Iraq.

Robby, Keith and I drank Hungarian wine and ate good steaks at Maxim’s while watching the floorshows: traditional Vietnamese musicians, singers and dancers followed by a Filipino band playing rock ‘n’ roll. A raucous party of Eastern Europeans sat nearby. After dinner we sat on the Majestic’s veranda for drinks. At one point I went to the front desk and was told that BBC refused to pay my hotel bill. I told Robby and Keith to wait a minute, walked to the Caravelle, told the panicked desk clerk – loudly, for the benefit of the attentive listeners – that I’d call my cop friends if BBC didn’t pay my bill by midnight.

Robby and Keith laughed when I told them what I’d done. They said they had a surprise for me and I should follow them. Which I did, without asking for any explanations. After several twists and turns, we found ourselves walking down a dark, narrow alley. As we approached the end of the alley, I saw a door to my left with a tiny sign above it: Lan Thanh. Against the opposite wall, a tiny charcoal fire cast the flickering shadows of huddled figures squatting on their haunches, sharing paraphernalia, smoking opium. Three girls dressed in dark, long-sleeved jackets and singing a silvery song, emerged from the door and ushered us inside. An older white man wearing blue jeans and a long-sleeved plaid shirt, with a white beard to his belt, stood at the corner of the bar near the door looking hypnotically down at his beer, as if high on heroin. I was sure he was American and suppressed the urge to ask, “What the fuck are you doing here?” The only other customer, a pimp I suppose, sat mid-bar fiddling with an ash tray and cigarette. The three giggling bar girls hustled us into the back of the room. Keith knew them well and they acted like they knew Robby too. The hierophants and their initiate.

We squeezed into a semi-circular leather booth at the rear of the saloon. As part of the ritual, the girls washed our arms and faces with damp cloths. While we ordered beers, they ceremoniously peeled fruit (juju with salt and oranges) and then sat perfectly still. In the deep darkness, all I could see was the radiant, beautiful face of the girl across from me. She smiled, her wide eyes saying “Yes, you can have me. Do you want me? Just say so. Why do you shy away? Don’t be ashamed of your desire. We can all see it here.”

Robby laughed at me and said, “Don’t make eye contact. That means you want to hire her.”

Anything you want you can get with just a look.

I told them about my bizarre canoe dream. Keith and Robby talked about their recurring MSG nightmares. The food is soaked in MSG, they said; it makes you wake up in a sweat, your heart racing. It’s a phenomenon that happens after you’ve been there about a week. The coffee gets into your system, cleans out the Western man. You start smelling like an Asian, acting like an Asian, thinking like an Asian, no pretensions, no hang-ups. After 30 days you’re taking advantage of every amenity the East has to offer. The price is MSG nightmares.

I started dozing off as they discussed the benefits of women with pelvic thrust backwards as opposed to pelvic thrust forward. They wanted to stay, and the bar girls wanted us to buy more drinks, but I needed rest. So Keith and Robby graciously led me out of the maze back to the hotel where we said a fond farewell. On my way to the elevator I passed the desk clerk without bothering to ask if the bill had been paid. I didn’t want to show concern. Too much pride.

Too much anxiety to sleep, too. But not anxiety about being detained in Vietnam. You can negotiate anything here. I was afraid of not succumbing. And of the loneliness I projected onto everyone around me.