Allegations regarding “Butch” Merritt, Watergate, Intelligence Agencies and “Crimson Rose,” Vol. IX

Nixon on Drugs – Part Two

Written (and first posted) by Kris Millegan, March 24, 2011

Look, the problem is that this will open the whole, the whole Bay of Pigs thing… Richard M. Nixon, June 23, 1972, Oval Office

The conventional wisdom is that Nixon used the “Bay of Pigs,” as a code word for the Kennedy Assassination, but it could just as well be code for “drug smuggling.” It’s an interesting crew.

From http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/JFKcorcoran.htm:

The OSS gradually took over the activities that Corcoran had helped set up in China. In 1943 OSS agents based in China included Paul Helliwell, E. Howard Hunt, Mitch Werbell, Lucien Conein, John Singlaub and Ray Cline. According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, some OSS members in China were paid for their work with five-pound sacks of opium.

Again, some detail from the 1980 out-of-print book, The Great Heroin Coup – Drugs, Intelligence, & International Fascism by Henrik Kruger:

FOURTEEN

HEROIN IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

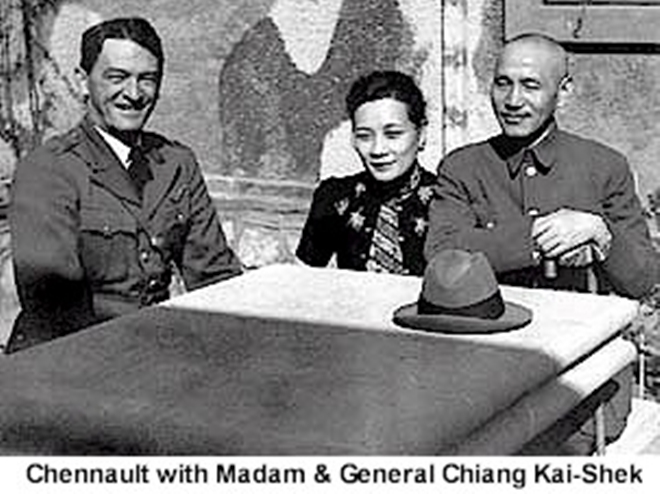

The place was Kunming in the South China province of Yunnan. The time was the end of World War II. Amid the chaos of war, opium and gold became the primary media of exchange, and cult‑like bonds were forged among a small staff of Americans and high‑ranking Chinese. Yunnan was a center of Chinese opium cultivation and Kunming was the hotbed of military operations, among them Claire Chennault’s 14th Air Force and Detachment 202 of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

Among Detachment 202’s notorious collection of special agents, one in particular – E. Howard Hunt – has needed no introduction since the Watergate break‑in. In Kunming, the spy novelist who later became a comrade of Cuban exiles and China Lobbyists befriended an equally intriguing character, the French Foreign Legionnaire turned OSS agent, Captain Lucien Conein.[1] Although not part of Detachment 202 proper, Conein frequented Kunming while awaiting parachuting over Indochina.[2]

Indochina remained Conein’s base of operation after World War II, when, like Hunt, he slid over from the OSS to its successor, the CIA. He then operated throughout South and North Vietnam, Cambodia, and Burma, and became the top U.S. expert on the area‑as well as on the opium‑smuggling Corsican Mafia. He was Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge’s middle-man in the 1963 plot to overthrow South Vietnam’s President Ngo Dinh Diem (who was assassinated along with his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu, the Corsicans’ partner in the drug traffic). A decade later, Conein and Hunt, working for the Nixon White House Plumbers, would attempt to make it appear that the plot had been ordered by JFK. Both Conein and William Colby, mastermind of the CIA’s Phoenix assassination program, were recalled to the U.S. at the start of the seventies.

After Mao Tse‑tung’s rise to power in China, OSS veterans formed a number of firms that would be linked both to the CIA and to its reactionary client regimes in the Far East. With financial assistance from his friends in Asia, OSS China hand C.V. Starr gained control of several U.S. insurance companies. As brought to light during the McClellan hearings, Jimmy Hoffa awarded one of them, U.S. Life, and a smaller company, Union Casualty‑whose agents Paul and Allen Dorfman were among Hoffa’s links to the underworld[3]—a Teamsters Union contract despite a lower bid from a larger, more reputable insurance firm.[4]

Starr’s attorney was the powerful Washington‑based Tommy “The Cork” Corcoran. Corcoran’s law partner, William Youngman, was a director of U.S. Life. Corcoran’s other clients included the United Fruit Company, Chiang Kai‑shek’s influential brother‑in‑law T.V. Soong, and the mysterious airline, Civil Air Transport (CAT), of which 60 percent was owned by the Taiwan regime and 40 percent by the CIA.[5] On behalf of United Fruit, Corcoran triggered a CIA plot — in which E. Howard Hunt was the agency’s chief political action officer — to overthrow Guatemala’s President Jacobo Arbenz in 1954.[6]

OSS China hand Willis Bird settled in Bangkok, Thailand to head an office of Sea Supply, Inc., a CIA proprietary headquartered in Miami, which furnished weapons to opium‑smuggling Nationalist Chinese (KMT) troops in Burma. One William Bird, representing CAT in Bangkok, coordinated CAT airdrops to KMT troops and ran an engineering firm that constructed short airstrips used for the collection of Laotian opimu.[7]

Sea Supply also provided arms and aid to Phao Sriyanonda, the head of Thailand’s 45,000‑man paramilitary police force and reputedly one of the most corrupt men in the history of that corruption‑ridden nation. For years his troops protected KMT opium smugglers and directed the drug trade from Thailand.[8]

When President John F. Kennedy in 1962 attempted a crackdown on the most hawkish CIA elements in Indochina, he sought the prosecution of Willis Bird, who had been charged with the bribery of an aid official in Vientiane. But Bird never returned to the U.S. to stand trial.

Upon returning to Miami, the OSS Chief of Special Intelligence and head of Detachment 202 in Kunming, Colonel Paul Helliwell, was a busy man. In Miami offices of the American Bankers Insurance Co. he functioned simultaneously as the Thai consul, an the counsel for Sea Supply as well as for insurance companies run by his former subordinate C.V. Starr.[9] American Bankers Insurance was itself a most unusual firm; one of its directors, James L. King, was also a director of the Miami National Bank through which the Lansky syndicate reportedly passed millions en route to Geneva’s Swiss Exchange and Investment Bank. One of the Swiss bank’s directors, Lou Poller, also sat on the board of King’s Miami National Bank.[10]

Moreover, in the fifties and sixties, Thai and Nationalist Chinese capital was invested in Florida’s explosive development, much of it by way of the General Development Corporation controlled by associates of Meyer Lansky.[11] It’s important to note the dubious alliance of Southeast Asian power groups with those concerned with Florida and Cuba. This early mutuality of business interests is the key to all that follows, and Miami is the nerve center to which we will continually return.

The alliance was comprised of the China Lobby, OSS China hands, Cuban exiles, the Lansky syndicate, and CIA hawks pushing for all‑out involvement in Indochina and against Castro’s Cuba. It coalesced between 1961 and 1963, and its members had three things in common: a right wing political outlook, an interest in Asian opium, and a thirst for political might. The last factor led to another common denominator in which the alliance invested heavily: Richard M. Nixon.

Some people effectively overlap the entire spectrum of the alliance. Among them are Howard Hunt and Tommy Corcoran, the man behind United Fruit’s dirty work. United Fruit was a client of the Miami‑based Double‑Chek Corp., a CIA front that supplied planes for the Bay of Pigs invasion.[12] Corcoran was the Washington escort of General Chennault’s widow Anna Chen Chennault, erstwhile head of the China Lobby, the key to Southeast Asian opium.[13]

Another key figure in the China Lobby was weapons dealer/financier William Pawley, the American cofounder of Chennault’s Flying Tigers.[14] Pawley’s name was the password to intrigue: OSS China, Tommy Corcoran,[15] CIA cover firms,[16] and arms shipments to KMT Chinese on Taiwan in defiance of a State Department refusal of authorization.” All were either directly or indirectly connected to Pawley. He also rubbed elbows with the U.S. heroin Mafia when, in 1963, he, Santo Trafficante, Jr. and Cuban exiles took part in one of the countless boat raids on Cuba.[18]

The China Lobby’s Southeast Asian connection naturally went via the Taiwan regime, which controlled the opium‑growing Chinese in the Golden Triangle and, with the CIA, owned the opium‑running CAT airlines. As Ross Y. Koen wrote in 1964:

“There is considerable evidence that a number of Nationalist Chinese officials are engaged in the illegal smuggling of narcotics into the United States with the full knowledge and connivance of the Nationalist Chinese government. The evidence indicates that several prominent Americans have participated in and profited from these transactions. It indicates further that the narcotics business has been an important factor in the activities and permutations of the China Lobby.” [19]

British writer Frank Robertson went one step further in 1977:

“Taiwan is a major link in the Far East narcotics route, and a heroin producer. Much of the acetic anhydride ‑the chemical necessary for the transformation of morphine into heroin ‑smuggled into Hong Kong and Thailand, comes from this island, a dictatorship under the iron rule of the late Chiang Kai‑shek’s son, Chiang Chingkuo.”[20]

When the Communists routed Chiang Kai‑shek’s forces in 1949, some 10,000 KMT troops fled to Southeast Asia and settled in a remote part of Burma. Heavily armed, they soon assumed control of the area and intermarried with the local population. Under General Li Mi they continued to infiltrate China proper, but each time they were repulsed. While awaiting Chiang’s signal for a final, two‑front onslaught, Burma’s KMT army needed a source of income. Many had grown opium in Yunnan and so the poppies, which flourished on the hillsides, became the force’s cash crop.

Around 1950 the CIA became interested in the KMT troops. With General Douglas MacArthur pushing to arm them for an attack on Red China, the agency secretly flew them weapons in CAT airplanes. But when the KMT instead used the weapons against the Burmese army, Burma protested before the UN, where it was decided that 2000 KMT troops would be flown by CAT to Taiwan by 1954. Those who eventually made the trip, however, were only farmers and mountain people in KMT uniforms, and the weapons they took out were obsolete.[21] Nonetheless, with help from the Red Chinese army, Burma drove most of the KMT forces into Thailand and Laos, though many later returned. The Kuomintang and their kin now number over 50,000. Though only a fraction are soldiers, the KMT still controls hundreds of thousands of Chinese occupying the region, especially in Thailand.

The junction of Burma, Thailand, and Laos, the Golden Triangle, is the site of the bulk of the world’s opium production and thereby the source of enormous fortunes for the French and later the Americans. The French held effective control over the Southeast Asian opium traffic until 1965. Between 1946 and 1955 the Mixed Airborne Commando Group (MACG) and the French Air Force managed the shipment of opium from Burma to Laos. A guerilla corps comprised mostly of Laotian Meo tribesmen and led by Colonel Roger Trinquier, MACG remained unusually independent despite its direct connections to the SDECE and Deuxieme (Second) Bureau. To finance their secret Indochina operations, these organizations turned to the smuggling of gold and opium, with MACG in charge of the latter. Large quantities of opium were shipped to French Saigon headquarters and passed on to the Corsican Mafia, who in turn smuggled the drug to Marseilles.

When the French withdrew from Indochina in 1955 after their defeat by the Vietminh, and after the CIA pushed aside the SDECE, MACG leaders communicating through CIA agent Lucien Conein offered the Americans their entire guerilla force. Against Conein’s advice they refused.[22] History would cast doubt on the wisdom of that decision.

In 1955 CIA agent General Edward Lansdale began a war to liquidate the Corsican supply network. While Lansdale was cracking down on the French infrastructure, his employer the CIA was running proprietaries, like Sea Supply and CAT, that worked hand‑in‑hand with the opium‑smuggling Nationalist Chinese of the Golden Triangle, and with the corrupt Thai border police.[23]

The Lansdale/ Corsican vendetta lasted several years, during which many attempts were made on Lansdale’s life. Oddly enough, his principal informant on Corsican drug routes and connections was the former French Foreign Legionnaire, Lucien Conein, then of the CIA. Conein knew just about every opium field, smuggler, trail, airstrip, and Corsican in Southeast Asia. He spent his free time with the Corsicans, who considered him one of their own. Apparently they never realized it was he who was turning them in.[24]

When Lansdale returned from Vietnam in the late fifties, the Corsicans recouped some of their losses, chartering aging aircraft to establish Air Opium, which functioned until around 1965. That year, the Corsicans’ nemesis Lansdale returned to Vietnam as an advisor to Amabassador[sic] Lodge. There was also an upheaval in the narcotics traffic, and perhaps the two were connected. CIA‑backed South Vietnamese and Laotian generals began taking over the opium traffic — and as they did so, increasing amounts of morphine and low‑quality heroin began showing up on the Saigon market.

The first heroin refineries sprang up in Laos under the control of General Ouane Rattikone. President Ky in Saigon was initially in charge of smuggling from the Laotian refineries to the South Vietnamese; and Lansdale’s office, it is to be remembered, was working closely with Ky. Lansdale himself was one of Ky’s heartiest supporters, and Conein went along with whatever Lansdale said.[25]

One result of the smuggling takeover by the generals was the end of the Corsicans’ Air Opium. The KMT Chinese and Meo tribesmen who cultivated raw opium either transported it themselves to the refineries or had it flown there by the CIA via CAT and its successor, Air America, another agency proprietary. Though the Corsicans still sent drugs to Marseilles, the price was becoming prohibitive, since they were forced to buy opium and morphine in Saigon and Vientiane rather than pick up the opium for peanuts in the mountains.

In 1967 a three‑sided opium war broke out in Laos between a Burmese Shan State warlord, KMT Chinese and General Rattikone’s Laotian army. Rattikone emerged victorious, capturing the opium shipment with the help of U.S.‑supplied aircraft. The KMT, for its part, managed to reassert its dominance over the warlord. The smuggling picture was becoming simplified, with Southeast Asian opium divided among fewer hands, and most of the Corsicans out of the way.

General Lansdale returned to the U.S. in 1967, leaving Conein in Vietnam. The next year Conein greeted a new boss, William Colby. Since 1962 Colby had run the agency’s special division for covert operations in Southeast Asia, where his responsibilities included the ” secret” CIA war in Laos with its 30,000‑man Meo army. He shared that responsibility with the U.S. ambassador [sic] in Laos, William H. Sullivan, who would later preside over the Tehran embassy during the fall of the Shah.

Many of the agents who ran the CIA’s war in Laos had earlier trained Cuban exiles for the Bay of Pigs invasion, and afterward had taken part in the agency’s continued secret operations against Cuba.[26] Since exiles were furnished by the Trafficante mob,[27] intelligence agents had intermingled with representatives of America’s number one narcotics organization. The same agents would now become involved with the extensive opium smuggling from Meo tribesmen camps to Vientiane.[28]

In 1967 Colby devised a plan of terror for the “pacification” of Vietnam. Operation Phoenix organized the torture and murder of any Vietnamese suspected of the slightest association with Vietcong. Just as Lansdale was travelling home, Colby was sent to South Vietnam to put his brainchild to work. According to Colby’s own testimony before a Senate committee, 20,857 Vietcong were murdered in Phoenix’s first two years. The figure of the South Vietnamese government for the same period was over 40, 000.[29[

It was during Colby’s tour in Vietnam that the heroin turned out by General Ouane Rattikone’s labs appeared in quantity, and with unusually high quality. The great heroin wave brought on a GI addiction epidemic in 1970; Congressional reports indicated that some 22 percent of all U.S. soldiers sampled the drugs and 15 percent became hooked.[30]

Former Air Marshal, then Vice President, Nguyen Cao Ky (now alive and well in the United States) and his underlings still controlled most of the traffic. President Nguyen Van Thieu and his faction, comprised mostly of army and navy officers, were also in it up to their necks. According to NBC’s Saigon correspondent, Thieu’s closest advisor, General Dang Van Quang, was the man most responsible for the monkey on the U.S. Army’s back. But the U.S. Saigon embassy, where Colby was second in command, found no substance to the accusations, Ky’s record notwithstanding: Ky had been removed from U.S. Operation Haylift, which flew commando units into Laos, for loading his aircraft with opium on the return trips.

In the face of skyrocketing GI heroin abuse, the Army Criminal Investigation Division (CID) looked into General Ngo Dzu’s complicity in the heroin traffic and filed a lengthy report at the U.S. embassy.[31] The embassy ignored the report and chose not to forward it to Washington.[32] The BNDD also investigated the roots of the heroin epidemic, but was impeded in its work by the CIA and U.S. embassy. In 1971, however, a string of heroin labs were uncovered in Thailand, and a number were closed down.

In 1971, furthermore, Colby and Conein were recalled to the United States. Colby became the Deputy Director of Operations, the man in charge of the CIA’s covert operations. More remarkable, though, was Conein’s homecoming after twenty‑four years of periodic service to the CIA in Indochina, raising the question of why the U.S.’s foremost expert on Indochina had been brought back to Washington just as the crucial phase of Vietnamization was about to begin.[33] Ironically, Corsican friends still around for Conein’s departure presented him with a farewell gold medallion bearing the seal of the Corsican Union.

At the war’s cataclysmic end, the CIA admitted that “certain elements in the organization” had been involved in opium smuggling and that the illegal activities of U.S. allies had been overlooked to retain their loyalties. In reality, the agency had been forced to confess because of its inability to refute the tales of returning GIs, among them that of Green Beret Paul Withers, a recipient of nine Purple Hearts, the Distinguished Service Cross and Silver and Bronze Stars:

“After completing basic training at Fort Dix in the fall of 1965 [Withers] was sent to Nha Trang, South Vietnam. Although he was ostensibly stationed there, he was placed on ‘loan’ to the CIA in January 1966 and sent to Pak Seng, Laos. Before going there he and his companions were stripped of their uniforms and all American credentials. They were issued Czechoslovakian guns and Korean uniforms. Paul even signed blank sheets of paper at the bottom and the CIA later typed out letters and sent them to his parents and wife. All this was done to hide the fact that there were American troops operating in Laos.

“The mission in Laos was to make friends with the Meo people and organize and train them to fight the Pathet Lao. One of the main tasks was to buy up the entire local crop of opium. About twice a week an Air America plane would arrive with supplies and kilo bags of opium which were loaded on the plane. Each bag was marked with the symbol of the tribe.”[34]

The CIA, reportedly, did not support any form of smuggling after 1968. Del Rosario, a former CIA operative, had something to say about that:

“In 19711 was an operations assistant for Continental Air Service, which flew for the CIA in Laos. The company’s transport planes shipped large quantities of rice. However, when the freight invoice was marked ‘Diverse’ I knew it was opium. As a rule an office telephone with a special number would ring and a voice would say ‘The customer here’‑that was the code designation for the CIA agents who had hired us. ‘Keep an eye on the planes from Ban Houai Sai. We’re sending some goods and someone’s going to take care of it. Nobody’s allowed to touch anything, and nothing can be unloaded,’ was a typical message. These shipments were always top priority. Sometimes the opium was unloaded in Vientiane and stored in Air America depots. At other times it went on to Bangkok or Saigon.[35]

Even while the CIA trafficked in opium, President Nixon ranted on TV against drug abuse and lauded the crackdown against French smuggling networks.

pps. 129-139

–[Notes]–

1. E.H. Hunt: Undercover (Berkeley‑Putnam, 1974).

2. Another of Conein’s OSS sidekicks, Mitchell WerBell III, was years later indicted in a major drug conspiracy case (T. Dunkin: “The Great Pot Plot,” Soldier of Fortune, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1977), and now runs an antiterrorist training school in Georgia (T. Dunkin: “WerBell’s Cobray School,” Soldier of Fortune, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1980).

3. D. Moldea: The Hoffa Wars (Charter Books, 1978).

4. U.S. Congress, Senate, Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, Hearings, 85th Cong., 2nd Sess. (cited in P.D. Scott: The War Conspiracy, Bobbs‑Merrill, 1972).

5. CAT, which became Air America, was also identical with the “CATCL” that emerged from Claire Chennault’s Flying Tigers.

6. D. Wise and T.B. Ross: The Invisible Government (Random House, 1964); Hunt, op. cit.

7. Scott, op. cit.

8. F. Robertson: Triangle of Death (Routledge and Keagen Paul, 1977); A. McCoy: The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia (Harper & Row, 1972).

9. Scott, op. cit.

10. New York Times, 1 December 1969; H. Messick: Lansky (Berkeley, 1971). 11. Carl 0. Hoffmann, the former OSS agent and general counsel of the Thai king in New York in 1945‑50, later became the chairman of Lansky associates’ First Florida Resource Corp.

12. L. Gonzalez‑Mata: Cygne (Grasset, 1976).

13. R.Y.Koen: The China Lobby in American Politics (Harper& Row, 1974). 14. Pawley, the ultraconservative former Pan Am executive and Assistant Secretary of both State and Defense, set up the Flying Tigers under a secret order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt exempting him from U.S. neutrality provisions; see A. Chan Chennault: Chennault’s Flying Tigers (Eriksson, 1963).

15. Corcoran assisted in the establishment of the Flying Tigers and later Civil Air Transport; see Scott, op. cit.

16. Lindsey Hopkins, Jr., whose sizable investments included Miami Beach hotels, was an officer of the CIA proprietary, Zenith Technical Enterprises of Bay of Pigs note. He was also an officer of the Sperry Corp., through whose subsidiary, the Intercontinental Corp., Pawley helped found the Flying Tigers in 1941. Pawley was Intercontinental’s president. See Scott, op. cit.

17. U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Judiciary, Communist Threat to the United States through the Caribbean, Hearings, 86th Cong., 2nd Sess. (cited in Scott, op. cit.).

18. See chapter fifteen; it has also been revealed that a prominent Chinese American, Dr. Margaret Chung of San Francisco, who was a major supporter of the Flying Tigers, trafficked in narcotics together with the Syndicate; see P.D. Scott: “Opium and Empire,” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, September 1973.

19. Koen, op. cit. 20. Robertson, op. cit.. After a one‑year suspension, the U.S. State Department recently approved the sale of $280 million in military weaponry to the repressive Taiwan regime (New York Times, 20 January 1980), the same regime whose disdain for human rights was most recently expressed by the preparation of cases of sedition against sixty‑five opposition demonstrators (New York Times, 24 January 1980). The CIA’s Taiwan station chief in the late fifties and early sixties, when the unholy alliances were forged, was Ray S. Cline. Closely associated with the China Lobby, Cline became famous for his drunken binges with Chiang Ching‑kuo, currently the president of Taiwan (see V. Marchetti and J.D. Marks: CIA and Cult of Intelligence, Jonathan Cape, 1974). A CIA hawk, Cline also helped a gigantic Bay of Pigs‑style invasion of the Chinese mainland which was rejected by President Kennedy. Cline is currently the “director of world power studies” at Georgetown’s Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), which, according to writer Fred Landis (“Georgetown’s Ivory Tower for Spooks,” Inquiry, 30 September 1979), “is rapidly becoming the New Right’s most sophisticated propaganda mill.” In testimony before the House Select Committee on Intelligence, Cline defended CIA manipulation of the press, saying “You know that first amendment is only an amendment.”

21. McCoy, op. cit.

22. D. Warner: The Last Confucian (Angus & Robertson, 1964). 23. McCoy, op. cit.

24. Conein told writer McCoy: “The Corsicans are smarter, tougher and better organized than the Sicilians. They are absolutely ruthless and are the equal of anything we know about the Sicilians, but they hide their internal fighting better.” (McCoy, op. cit.).

25. McCoy, op. cit.

26. T. Branch and G. Crile III: “The Kennedy Vendetta,” Harper’s, August 1975.

27. U.S. Congress, Senate, Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with respect to Intelligence Activities, Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders, Interim Report, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. Senate Report No. 94‑463, 1975.

28. C. Lamour and M.R. Lamberti: Les Grandes Maneuvres de l’0pium (Editions du Seuil, 1972); McCoy, op. cit.; Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars: The Opium Rail (New England Free Press, 1971).

29. Marchetti and Marks, op. cit.

30. Congressman M.F. Murphy and R.H. Steele: The World Heroin Problem (U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1971).

31. Like Nguyen Cao Ky, Ngo Dzu came to the U.S. as a refugee after the final debacle in South Vietnam. Though accused by Rep. Steele of responsibility for the addiction of thousands of GIs to heroin, Dzu went about as a free man until his 13 February 1977 death in Sacramento of apparent heart failure.

32. McCoy, op. cit.

33. Conein’s summons home coincided with Howard Hunt’s recruitment by the White House and the creation of the special narcotics and Plumbers groups. 34. Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars, op. cit. 35. Lamour and Lamberti, op. cit. (quote retranslated from the French).

=====

FIFTEEN

THE CUBANS OF FLORIDA

Meyer Lansky, the Syndicate’s financial wizard and its chairman from around 1947, began building his Cuban empire in the early forties. When free elections chased his close friend and dictator Fulgencio Batista from office in 1944, Lansky also left the island, entrusting his empire to the Trafficante family headed by Santo, Sr. Lansky and Batista settled in Hollywood, Florida, just north of Miami. Before long, Lansky was running an illegal casino empire on the coast, and in 1947 he eliminated Bugsy Siegel and moved into Las Vegas.

All the while Lansky expanded the narcotics trade founded by Lucky Luciano. The older Mafia dons deemed the trade taboo, so Lansky’s wing of the Syndicate cornered the market, with Trafficante’s eldest son, Santo, Jr., overseeing the heroin traffic.[1]

When Florida’s illegal casinos were shut down in 1950, Lansky promoted Batista’s return to power in Cuba. The drive bore fruit in 1952. With Trafficante, Sr.’s death in 1954, Santo, Jr. became Lansky’s right‑hand man and manager of his Cuban interests. Until then, he had managed the Sans Souci Casino, a base for running Havana’s tourist trade and keeping tabs on heroin shipments from Marseilles to New York via Florida and Cuba.[2]

Trafficante, Jr. has proven more talented than his father. Extraordinarily intelligent and energetic, he has handled the most acute crises with detached calm. Luciano characterized him as “. . a guy who always managed to hug the background, but he is rough and reliable. In fact, he’s one of the few guys in the whole country that Meyer Lansky would never tangle with.”[3]

In no time, Trafficante, Jr. ingratiated himself with dictator Batista, while remaining loyal to Lansky, who appointed him manager of his own Florida interests in addition to those in Cuba. Lansky needed to spend increasing amounts of time in New York, between travels to Las Vegas, Rome, Marseilles, Beirut, and Geneva.

Many envied Lansky’s ever‑increasing power and wealth, among them Murder, Inc. chairman of the board Albert Anastasia. In 1957 the latter tried enlisting Trafficante’s aid in removing Lansky from the Havana scene. It was one of Anastasia’s last moves. Trafficante arranged a “friendly” meeting in New York’s Sheraton Hotel. An hour after Trafficante had checked out, Anastasia was murdered in the hotel’s barber shop, shaving cream still on his face.[4]

According to Peter Dale Scott, “certain U.S. business interests collaborated with the narcotics‑linked American Mafia in Cuba‑as they did with similar networks in China and later in Vietnam ‑for the Mafia supplied the necessary local intelligence, cash and muscle against the threat of communist takeover.[5] As Scott wrote those words in 1973, Cuban‑Americans recruited by the CIA were suspected by federal and city authorities to be “involved in everything from narcotics to extortion rackets and bombings.”[6] The Church committee and other Senate and law enforcement reports would confirm these allegations.

Again we observe the Cuba/ Southeast Asia/ CIA triangle, and it’s no secret who managed the Cuban side. There Trafficante, Jr. hired the fast‑learning natives, while dictator Batista’s men made the empire safe for organized crime, often appearing more loyal to Trafficante than to Batista himself. In return the Cubans learned the business.

With Fidel Castro’s 1 January 1959 ouster of Batista, Lansky and Trafficante were in trouble. Though they were expelled from their Cuban kingdom, nearly a year elapsed before the Syndicate departed and the casinos were closed. Along with ‘Trafficante and Lansky, half a million Cubans left the island in the years following Castro’s takeover. Some 100,000 settled in the New York City area, especially Manhattan’s Washington Heights and New Jersey’s Hudson County. Another 100,000 headed to Spain, others to Latin America, and a quarter of a million made their new home in Florida, the site of Trafficante’s new headquarters.

Out of the Trafficante‑trained corps of Cuban officers, security staffers and politicians, a Cuban Mafia emerged under the mobster’s control. It specialized in narcotics, first Latin American cocaine, then Marseilles heroin. With his Cubans Trafficante also grabbed control of La Bolita, the numbers game that took Florida by storm and became a Syndicate gold mine.[7]

Besides the Cubans, who comprised the main wing of his organization, Trafficante also worked closely with the non‑Italian Harlan Blackburn mob, a break with Mafia tradition.[8] But the core of the Trafficante family remained Italian, and the Italians also dealt in drugs. In 1960 his man Benedetto “Beni the Cringe” Indiviglio negotiated the opening of a narcotics route with Jacques I’Americain, the representative of Corsican boss Joseph Orsini.[9] Benedetto and his brothers Romano, Arnold, Charles and Frederick eventually ran Trafficante’s Montreal‑bound smuggling network, and were later joined by the notorious New York wholesaler Louis Cirillo.[10]

Trafficante settled in Tampa, but continued to run some of his activities from Jimmy Hoffa’s Teamster Local 320 in Miami. Traffiicante and David Yaras of Sam Giancana’s Chicago mob were instrumental in founding Local 320, which, according to the McClellan hearings, was a front for Syndicate narcotics activities.[11]

After losing his Havana paradise, far‑sighted Meyer Lansky used straw men to buy up much of Grand Bahama Island and erected a new gambling center around the city of Nassau. But though Lansky and Trafficante each survived in style, neither they nor the Cuban exiles relinquished hope of a return to Cuba. Moreover, they were not alone in dreaming of overthrowing Castro. The CIA in particular let its imagination run wild to this end. Its covert operations expert, General Edward Lansdale, seriously planned to send a submarine to the shore outside Havana, where it would create an inferno of light. At the same time, Cuba‑based agents would warn the religious natives of the second coming of Christ and the Savior’s distaste for Fidel Castro. However, “Elimination by Illumination” was shelved in favor of less fantastic suggestions for Castro’s assassination. The latter brought together the CIA, Cuban exiles, and the Syndicate in the person of Santo Trafficante.

In 1960 the CIA asked its contract agent Robert Maheu to contact the mobster John Roselli. Roselli introduced Maheu to Trafficante and Sam Giancana, the Chicago capo, and the strange bedfellows arranged an attempt on the life of Castro.[12] The agency had previously stationed an agent on Cuba who was to flash the green light when assassination opportunities arose. He was Frank Angelo Fiorini, a one‑time smuggler of weapons to Castro’s revolutionary army, to whom Castro had entrusted the liquidation of the gambling casinos.[13]

Through the latter assignment Fiorini had made the acquaintance of Trafficante.

In February 1961 Maheu, `Trafficante and Roselli met at Miami’s Fountainebleu Hotel. There Maheu gave the hoods untraceable poison capsules for delivery to a Cuban exile connected with the Trafficante mob.[14] 0ther Cubans were to smuggle them to the island and poison Castro; but the attempt failed. Trafficante engineered more attempts, including one in September 1962,[15] and his organization also provided Cubans for the Bay of Pigs invasion.[16]

Never before had there existed a more remarkable, fanatical group of conspirators than that assembled to create, finance, and train the Bay of Pigs invasion force. The top CIA figures were Lansdale protege Napoleon Valeriano, the mysterious Frank Bender, and E. Howard Hunt, who was himself involved in at least one of the attempts on Fidel Castro’s life. They were supported by a small army of CIA operatives from four of its Miami cover firms.[17]

Runner‑up to Hunt for the Most Intriguing CIA Conspirator award is Bender, a German refugee whose true identity remains a matter of speculation. Some contend that he had been an agent of the West German Gehlen espionage network under the name Drecher; others contend it was Droller.[18] The former security chief for Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo claims that Bender was in fact one Fritz Swend, a Gehlen collaborator and leader of ex‑Nazis in Peru. Prior to the Bay of Pigs invasion Swend was allegedly the CIA’s man in the Dominican Republic as Don Frederico. There he purportedly planned the invasion along with mobster Frank Costello and exCuban dictator Batista.[19]

The invasion’s moral and financial supporters included many leading China Lobbyists. Most important was the multi‑millionaire behind Claire Chennault’s Flying Tigers, William Pawley.[20] Pawley had been involved in the CIA’s 1954 overthrow of Guatemala’s democratically elected Arbenz regime. Like Lansky and Trafficante, Pawley had had a big stake in Cuba. Prior to Castro’s takeover he had owned the Havana bus system and sugar refineries. He met with President Eisenhower several times in 1959 to persuade the president to assist Cuban exiles in overthrowing Castro. Pawley then helped the CIA recruit anti‑Castro Cubans.[21]

The key Cuban exile conspirators in the Bay of Pigs operation and the ensuing attacks on Cuba and Castro included Manuel Artime, Orlando Bosch, Felipe de Diego, and Rolando Martinez ‑the first a close ‑friend of Howard Hunt’s, the last two future Watergate burglars. The name of Bosch was to become synonymous with terrorism.

Distinguishing the noncriminal element among the Bay of Pigs’ anti‑Castro Cubans is no easy matter, since so many emerged from Trafficante’s Cuban Mafia. According to agents of the BNDD, nearly 10 percent of the 1500‑man force had been or eventually were arrested for narcotics violations.[22] Its recruiters included Syndicate gangsters like Richard Cain, the former Chicago policeman who became a lieutenant for Sam Giancana.

The Dominican Republic, a focal point in the invasion scheme, also became a transit point for Trafficante’s narcotics traffic. Furthermore, the CIA, according to agents of the BNDD, helped organize the drug route by providing IDs and speedboats to former Batista officers in the Dominican Republic in charge of narcotics shipments to Florida.[23]

It is of paramount importance to note the close CIA cooperation with Trafficante’s Cuban Mafia, whose overriding source of income was the smuggling of drugs.

One of Trafficante’s personal CIA contacts for the Bay of Pigs was Frank Fiorini, Castro’s liquidator of Mob casinos, who now preferred the name Frank Sturgis.[24] In late 1960 Sturgis ran the Miami‑based International Anti‑Communist Brigade (IACB), said to be financed by the Syndicate.[25] According to Richard Whattley, a brigade member hired for the invasion, “Trafficante would order Sturgis to move his men and he’d do it. Our ultimate conclusion was that Trafficante was our backer. He was our money man.”[26]

Another detail from Sturgis’s past is especially interesting in light of Frank Bender’s alleged ties to the Gehlen organization. For a period in the early fifties Sturgis was involved in espionage activities in Berlin, serving as a courier between various nations’ intelligence agencies, and was thereby inevitably in contact with the Gehlen network.[27]

The Bay of Pigs invasion was, of course, a fiasco. But that hardly stopped the CIA, the Syndicate, or their Cuban exile troops. Wheels were soon turning on new assassination attempts under CIA agent William Harvey, who again collaborated with the underworld. Within months, the Miami CIA station JM/Wave was again in full swing. It sponsored a series of hit‑and‑run attacks on strategic Cuban targets that spanned three years and involved greater manpower and expenditures than the Bay of Pigs invasion itself.

To head the JM/Wave station, the CIA chose one of its up‑and‑coming agents, the thirty‑four year old Theodore Shackley, who came direct from Berlin. His closest Cuban exile associates were Joaquin Sangenis and Rolando (Watergate burglary) Martinez.[28] Some 300 agents and 4‑6000 Cuban exile operatives took part in the actions of JM/Wave. As later revealed, one of its last operations was closed down because one of its aircraft was caught smuggling narcotics into the United States.[29]

Shackley is another contender for the Most Intriguing CIA Conspirator award. After years of collaboration with Trafficante organization Cubans, he and part of his Miami staff were transferred to Laos,[30] where he joined Lucien Conein.[31] There they helped organize the CIA’s secret Meo tribesmen army, the second such army drummed up by Shackley that was up to its ears in the drug traffic.

Vientiane, where Shackley was the station chief, became the new center of the heroin trade. Later he ran the station in Saigon, where the traffic flowed under the profiteering administration of Premier Nguyen Cao Ky. When the agency prepared its coup against the Chilean President Salvador Allende, Shackley was its chief of covert operations in the Western Hemisphere. When William Colby became the director of the CIA in 1973, Shackley took over his job as chief of covert operations in the Far East. Eventually he was booted out of the agency as part of the shakeup ordered by its current director Stansfield Turner.[32]

In the JM/Wave period a great expansion in China Lobby‑Traffiicante‑Cuban exile‑CIA connections occurred. William Pawley financed a mysterious summer 1963 boat raid against Cuba in his own yacht, the Flying Tiger II. Besides Pawley himself, the crew included mafioso John Martino, who had operated roulette wheels in one of Trafficante’s Havana casinos; CIA agents code‑named Rip, Mike, and Ken; the ubiquitous Rolando Martinez; and a dozen other Cuban exiles led by Eddie Bayo and Eduardo Perez, many of whom eventually disappeared mysteriously.[33] Loren Hall, another former Trafficante casino employee, claimed that both his boss and Sam Giancana had helped plan the raid.[34] CIaire Boothe Luce, a queenpin of the China Lobby, testified during Senate hearings on the CIA that she had financed an exile gunboat raid on Cuba after JFK had ordered the agency to halt such raids.

I will not wander deeply into the quagmire of circumstances surrounding the murder of President John F. Kennedy. However, it is worth repeating a few lines from the final report of the House Select Committee on Assassinations: “The Committee’s extensive investigation led to the conclusion that the most likely family bosses of organized crime to have participated in such a unilateral assassination plan were Carlos Marcello and Santo Trafficante.”[35]

Of the many connections between Trafficante and Dallas the most important are his association with Jack Ruby, who visited him in a Havana prison in 1959; his statement to Cuban exile financier Jose Aleman that Kennedy “is going to be hit”; and his close association with fellow Mafia capo Carlos Marcello. The Cuban exiles, drug racketeers, and the CIA had no shortage of anti‑Kennedy motives, which were all the more intensified as the three forces gradually welded together.

The anti‑Cuba actions continued well into 1965, at which time a crucial three‑year turnabout for the Lansky Syndicate began. Its money had been invested in the unsuccessful attempts at toppling Castro and in its new casino complex in Nassau, which was threatened by local antigambling forces. So when Southeast Asia began emerging as a new heroin export center, Lansky sent his financial expert John Pullman to check out the opportunities for investment. Close on his heels went Frank Furci, the son of a Trafficante lieutenant.[36]

From 1968 on, Trafficante’s Cubans were in effective control of the traffic in heroin and cocaine throughout the United States.[37] The Florida capo’s only gangland partner of significance was the Cotroni family in Montreal.

Trafficante carried out his business in a cool and collected manner. Never out of line with the national Syndicate, he enjoyed relative anonymity while other, less prominent gangsters wrote their names in history with blood. His organization was so airtight that when narcotics investigators finally realized how big a fish he was, they had to admit he was untouchable. The BNDD tried nabbing him in its 1969‑70 OperationEagle, then the most extensive action ever directed against a single narcotics network. The Bureau arrested over 120 traffickers, wholesalers, and pushers, but made no real dent. Within days, well‑trained Cubans moved into the vacated slots.[38]

To the BNDD’s surprise, a very large number of those arrested in Operation Eagle were CIA‑trained veterans of the Bay of Pigs and Operation 40. Among them were Juan Cesar Restoy, a former Cuban senator under Batista, Allen Eric Rudd‑Marrero, a pilot, and Mario Escandar.[39] Their fates were most unusual. Escandar and Restoy, alleged leaders of the narcotics network, were arrested in June 1970 but fled from Miami City Jail in August. Escandar turned himself in, but was released soon afterward when it was established that Attorney General John Mitchell had neglected to sign the authorization for the wiretap that incriminated Escandar. He returned to narcotics and was arrested in 1978 for kidnapping, a crime punishable by life, but for which he got only six months.[40] As this book went to press the FBI was investigating Escandar’s relationship with the Dade County (Miami) police force.

Juan Restoy, on the other hand, turned to blackmail. He threatened to expose a close friend of President Nixon’s as a narcotics trafficker, if not given his freedom and $350,000.[41] Restoy was shot and killed by narcotics agents, as was Rudd‑Marrero.

In late 1970, in the wake of Operation Eagle, Bay of Pigs veteran Guillermo Hernandez‑Cartaya set up the World Finance Corporation (WFC), a large company alleged to be a conduit for Traffiicante investments and for the income from his narcotics activities.[42] Duney PerezAlamo, a CIA‑trained explosives expert involved with several Cuban exile terrorist groups, was a building manager for the WFC. Juan Romanach, a close Trafficante associate, was a WFC bank director.[43] As Hank Messick put it:

“Escandar, of course, was a friend of Hernandez‑Cartaya, who was a friend of Dick Fincher, who was a friend of Bebe Rebozo, who was a friend of Richard Nixon, who once told John Dean he could get a million dollars in cash.[44]

In 1968 Trafficante himself went on an extended business trip to the Far East, beginning in Hong Kong, where he had located his emissary Frank Furci .[45] After a slow 1965‑66 start, Furci had made great headway. Through his own Maradem, Ltd. he had cornered the market on Saigon’s night spots catering to GIs.[46] He even ran officer and soldier mess halls, and he had set up a chain of heroin labs in Hong Kong to serve the GI market.

From Hong Kong, Trafficante journeyed to Saigon, registering at the Continental Palace hotel owned by the Corsican Franchini family. His last stop was in Singapore, where he contacted a branch of the splintered Chinese Mafia.

Several doors had to be opened to gain access to the opium treasure. The first led to the CIA‑controlled&iwan regime, the second to the Golden Triangle’s KMT Chinese and Laotian Meo tribesmen. The latter door had already been opened by the CIA. Still another led to the Triads (Chinese gangster organizations) in Hong Kong. Traffiicante opened that door with the help of Furci, who gave him access to Southeast Asia’s overseas Chinese. There was no way around the Nationalist Chinese suppliers and middle men. The world had long been told that the narcotics came from Red China, but the facts belied that propaganda claim.[47]

Trafficante liked what he saw in his Southeast Asian tour. With enough trained chemists, his Mob could be supplied with heroin at a fraction of what it was then paying out to the Corsicans. But first the smuggling networks had to be worked out and the Corsicans had to be eliminated.

So Santo Traffiicante began his war against the Corsicans.[48] His major foe, Auguste Ricord in Paraguay, wasn’t about to roll over and die. Ricord got hold of his own Hong Kong connection, Ng Sik‑ho,[49] also known as “Limpy Ho,” a major Nationalist Chinese heroin smuggler well‑connected to the Taiwan regime.[50] After Ricord’s emissaries had travelled twice in 1970 to Japan, where they met with Mr. Ho,[51] heroin shipments began going to Paraguay via, among other transit points, Chile. 62 When in 1972 Ricord was extradited to the U.S., Limpy Ho tried establishing his own smuggling route to the U.S. via Vancouver. But that failed when two of his lieutenants, Sammy Cho and Chang Yu Ching, were arrested in the U.S. with fifty pounds of pure heroin.

By early 1970, Southeast Asian‑produced heroin was ready to be tested on GI guinea pigs. Meyer Lansky, facing charges of business illegalities, turned over control to Trafficante and fled to Israel. On July 4 Lansky narcotics associates reportedly made their investment plans for Southeast Asia at a twelve‑day meeting with representatives of several Mafia families at the Hotel Sole in Palermo, Sicily.[53]

Weeks later the Corsican Mafia contemplated counter‑moves in a meeting at Philippe Franchini’s suite in Saigon’s Continental Palace Hotel. Turkish opium production was already waning and could no longer be relied upon. Unrest in the Middle East was destabilizing the production of morphine base. The Corsicans had to do something to regain control over their longtime Southeast Asian domain, a task made all but impossible by the U.S. presence. But the Corsicans still had large stocks of morphine, their Marseilles labs, and a smoothly functioning smuggling network. Trafficante and company could agree that if the Corsicans were to be neutralized, it had to be done totally and effectively. That was a job for President Nixon and his White House staff, the BNDD/White House Death Squad, and the Central Intelligence Agency.

pps. 141-152

–[Notes]–

1. Santo Trafficante, Jr.’s first important appearance in his role as overseer of the heroin traffic might have been at a 1947 summit in Havana reportedly attended by Auguste Ricord, alias Lucien Dargelles, the French Nazi collaborator who became Latin America’s narcotics czar; see V. Alexandrov: La Mafia des SS (Stock, 1978).

2. A.McCoy: The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia (Harper& Row, 1972).

3. M. Gosch and R. Hammer: The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano (Little, Brown & Co., 1974).

4. Lansky was not then entirely sure of T~afficante’s loyalty. He had the latter swear a “holy” oath, witnessed by Vincent Alo: “With an ancient Spanish dagger — none from Sicily was available — Trafficante cut his left wrist, allowed the blood to flow, and wet his right hand in the crimson stream. Then he held up the bloody hand: ‘So long as the blood flows in my body,’ he intoned solemnly, ‘do 1, Santo Trafficante, swear allegiance to the will of Meyer Lansky and the organization he represents. If I violate this oath, may I burn in Hell forever.'” — H. Messick: Lansky (Berkeley, 1971).

5. P.D. Scott: “From Dallas to Watergate,” Ramparts, November 1973.

6. New York Times, 3 June 1973.

7. E. Reid: The Grim Reapers (Bantam, 1970).

8. Ibid.

9. P. Galante and L. Sapin: The Marseilles Mafia (W.H. Allen, 1979).

10. The Newsday Staff: The Heroin Trail (Souvenir Press, 1974).

11. D. Moldea: The Hoffa Wars (Charter Books, 1978).

12. U.S. Congress, Senate, Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with respect to Intelligence Activities, Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders, Interim Report, 94th Cong., 1st Sess., Senate Report No. 94‑463, 1975. (Henceforth referred to as Assassination Report).

13. P. Meskill: “Mannen som Ville Myrde Fidel Castro,” Vi Menn, 1976.

14. Assassination Report, op. cit.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. D. Wise and T.B. Ross: The Invisible Government (Random House, 1964);

P.D. Scott: The War Conspiracy (Bobbs‑Merrill, 1972).

18. The name Drecher appears in T. Szulc: Compulsive Spy (Viking, 1974); Droller is used in P. Wyden: The Bay of Pigs (Simon & Schuster, 1979).

19. L. Gonzalez‑Mata: Cygne (Grasset, 1976). According to this source (the author was the chief of security for the Dominican Republic’s dictator, Rafael Trujillo), Howard Hunt went to the Dominican Republic with the mobster John Roselli in March 1961.

20. Pawley eventually built five large airplane factories around the world. It is also likely that he was involved in the CIA’s Double Chek Corp. in Miami, as he had similarly been in the Flying Tigers. The CIA’s air proprietaries are said to stick together. When in 1958, CIA pilot Allen Pope was shot down and taken prisoner in Indonesia, he was flying for CAT. When he was released in 1962 he began flying for Southern Air Transport, another agency proprietary, which operated as late as 1973 out of offices in Miami and Taiwan. Southern’s attorney in 1962 was Alex E. Carlson, who a year before had represented Double Chek when it furnished pilots for the Bay of Pigs invasion; see V. Marchetti and J.D. Marks: CIA and the Cult of Intelligence (Jonathan Cape, 1974). On 23 March 1980, just as Iran’s revolutionary government was about to request that Panama extradite Shah Reza Palevi, the ex‑dictator who had been installed on his throne in 1953 by a CIA coup, he was flown off to Cairo on an Evergreen International Airlines charter. As reported by Ben Bradlee of the Boston Globe, (20 April 1980), in 1975 Evergreen had assumed control over Intermountain Aviation, Inc., a CIA proprietary. George Deele, Jr., a paid consultant for Evergreen, controlled the CIA’s worldwide network of secret airlines for nearly two decades.

21. M. Acoca and R.K. Brown: “The Bayo‑Pawley Affair,” Soldier of Fortune, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1976.

22. The Newsday Staff, op. cit.

23. H. Kohn: “Strange Bedfellows,” Rolling Stone, 20 May 1976.

24. The main character in Howard Hunt’s 1949 spy novel, Bimini Run, was “Hank Sturgis.”

25 . H. Tanner: Counter‑Revolutionary Agent (G.T. Foules, 1972).

26. Kohn, op. cit.

27. Meskill, op. cit.

28. Shackley was also indirectly responsible for Martinez’s participation in the 17 June 1972 Watergate breakin; see T. Branch and G. Crile III: The Kennedy Vendetta,” Harper’s, August 1975.

29. New York Times, 4 January 1975.

30. Branch and Crile, op. cit.

31. J. Hougan: Spooks (William Morrow, 1978).

32. Shackley might also have been responsible for the CIA’s tapping of all telephone converstions to and from Latin America in the first half of 1973 “in connection with narcotics operations” (see Newsweek, 23 June 1975). According to Branch and Crile, op. cit., Shackley, as chief of the CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division of Clandestine Services, “had overall responsibility for the agency’s efforts to overthrow the Allende regime in Chile.”

In a recent article in which he refers to Shackley as one of “the CIA’s most esteemed officers,” journalist Michael Ledeen claims that Shackley left the agency voluntarily when “forced to choose between retirement and accepting a post that would have represented a de facto demotion.” (New York, 3 March 1980). Ledeen, incidentally, is a colleague of Ray S. Cline at Georgetown’s rightwing propaganda mill, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (see chapter 14, footnote 20).

33. Acoca and Brown, op. cit.

34. D. Russell: “Loren Hall and the Politics of Assassination,” Village Voice, 3 October 1977.

35. The New York Times, ed.: The Final Assassinations Report (Bantam, 1979). In early 1980 the Justice Department was investigating allegations that Marcello had offered Mario T. Noto, the Deputy Commissioner of Immigration, a guaranteed “plush job” after retirement, in return for Noto’s help in lifting Marcello’s travel restrictions. Noto’s attorney, ironically, is Myles Ambrose, who stepped down from his job at the head of the BNDD in the wake of corruption allegations. (New York Times, 11 February 1980).

36. McCoy, op. cit.

37. H. Messick: The Mobs and the Mafia (Spring Books, 1972). 38. The Newsday Staff, op. cit.

39. H. Messick: Of Grass and Snow (Prentice‑Hall, 1979); The Newsday Staff, op. cit.

40. Miami Herald, 30 March 1978.

41. Messick: Of Grass and Snow, op. ‑cit.

42. Ibid.

43. Ibid.

44. Ibid.

45. McCoy, op. cit.

46. Ibid.

47. In the early seventies the opium bankrollers in Taiwan sent out, through their international lobby, the WACL, propaganda charging Red China with “the drugging of the world.” The propaganda was directed at Nixon’s rapprochement with mainland China. A 1972 BNDD report stated, however, that “not one investigation into heroin traffic in the area in the past two years indicates Chinese Communist involvement.”

48. The existence of such a drug war is also mentioned in A. Jaubert: Dossier D … comme Drogue (Alain Moreau, 1974).

49. S. O’Callaghan: The Triads (W.H. Allen, 1978).

50. F. Robertson: Triangle of Death (Routledge and Keagen Paul, 1977). 51. O’Callaghan, op. cit.

52. McCoy, op. cit.

53. F. Wulff in the Danish Rapport, 14 April 1975. A BNDD agent on the scene was reportedly discovered and liquidated. Apparently he hadn’t known that the code words were “baccio la mano” — I kiss your hand. Subject number one of the meeting was Southeast Asia, which the conferees decided would replace Turkey and Marseilles as the main source of opium and heroin. Mexico, to which Sam Giancana was sent, would be a safety valve. On one thing they were uananimous: the Corsicans had to be eliminated. To begin with, $300 million was to be invested in the bribery of politicians, as well as of military and police officers in Thailand, Burma, Laos, South Vietnam, and Hong Kong. Another nine‑figure sum was set aside to maximize opium production in the Golden Triangle.

to be continued…

Watergate Exposed: How the President of the United States and the Watergate Burglars Were Set Up (as told to Douglas Caddy, original attorney for the Watergate Seven), by Robert Merritt is available at TrineDay, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, The Book Depository, and Books-a-Million.